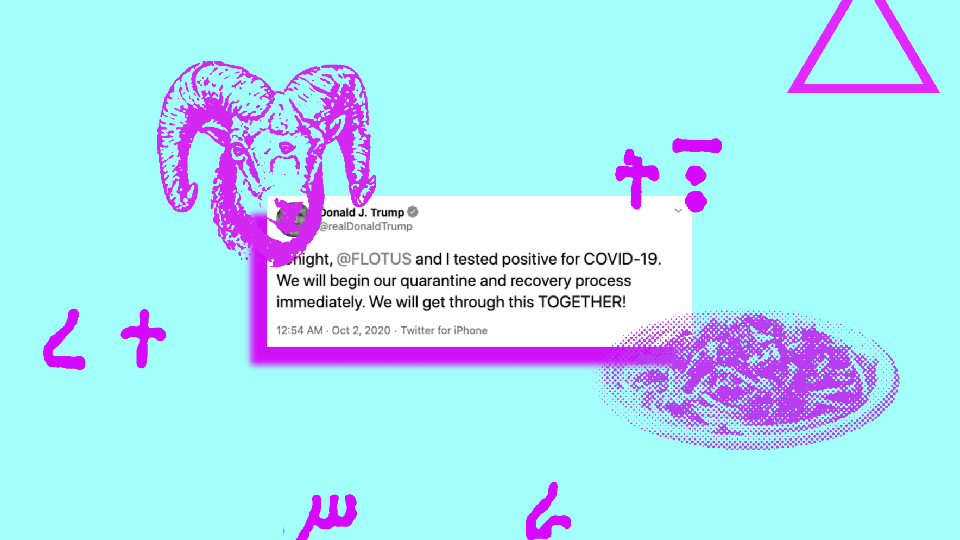

When Donald Trump announced that he and his wife, Melania, had tested positive for COVID-19, the replies were full of well-wishing, as well as admonishments from others for not being careful. Less expected was a whole host of messages full of indecipherable hexes, pictures of demons, and cursed images of all kinds.

“The dead are resurrected day and night without anyone knowing,” reads one tweet written in Punjabi and paired with an image of what appears to be a young female ghost. Others are in Amharic, an Ethiopian language, and say things like “Arise from the ashes of your wickedness and repent before our Lord Lucifer pays your debts”; still others have text atop an image of a ram with three eyes, or a skateboarder wearing plates of pasta as shoes.

The creepy meme format has been popping up over and over, including in the replies to many of Trump’s tweets from the hospital over the weekend and then after he returned to the White House on Monday. Other high-profile Republicans such as Kellyanne Conway who tested positive in recent days have also faced the wrath. The accounts posting do not appear to be bots, which sometimes clog up the coveted real estate of Trump’s Twitter replies. They seem to be real people, sharing copypasta—chunks of text that get copy-and-pasted all over social media, a spammy internet custom. They are not actually hexing the president. They are joking. One account usually dedicated to promoting the singer Doja Cat tweeted a Punjabi phrase at Trump with an image of a demonic Baby Yoda, then clarified that they were doing it because it was funny.

If the joke makes no sense, that’s the point. This style of scary tweet was popularized earlier this summer by a handful of enormous pop-music fandoms that used it as a pointless trolling tactic. That it’s now bled over into the president’s mentions is indicative of just how ubiquitous stan culture has become. Memes that were once niche now inform how huge numbers of people react to or experience major news events.

[Read: The joke’s on us]

Though a few of these phrases have drifted around odd corners of the internet for some time, it was stan culture that brought them out of obscurity and turned them into meme campaigns. The most common Punjabi phrase people are using to hex the president seems to have originated in a tweet unrelated to Trump, from a fan account dedicated to Cory Monteith, the Glee star who died in 2013. The phrase was picked up for hexing by fans of the K-pop group BTS and the rapper Nicki Minaj, as well as a random assortment of internet oddballs. And Amharic phrases similar to the ones being tweeted at the president were used by hundreds of Taylor Swift fans earlier this summer, who tweeted them at music critics they believed had given the singer’s new album unsatisfactory reviews. In that case, the text was usually paired with images of Swift Photoshopped to look like a demon, but since Friday, they have been paired with all kinds of haunting scenes: a Lego character with human skin, a giant tarantula with the arms of a man, Teletubbies with black holes for eyes, the Long Furby. But it remains unclear how Swift fans originally stumbled across this tactic for Twitter taunting, or why exactly they chose Amharic for it. They obviously think it looks spooky, though others have criticized them for this cultural insensitivity.

The hexes are similar to—but far more aggressive than—another common fandom tactic: replying to everything with homemade “fan cam” clips of one’s favorite star. Both are methods of sowing chaos and derailing the logic of a conversation, and often they don’t even involve any explicit organization. Networks of fan accounts have been so coordinated for so long that they can make something a trend without trying—even a fake curse in an arbitrarily chosen foreign language.

Not so long ago, the antics of stans were generally focused on issues related to pop music and celebrity, and typically siloed by fandom—Ariana Grande and Nicki Minaj and Justin Bieber fans keeping to their own, unless they were warring with one another. But now the experience of being online is a stan-culture experience for nearly everyone—a big, somewhat generic, and somewhat hallucinatory one. Earlier this summer, K-pop fans used fan cams to taunt QAnon supporters and people who were tweeting things like “White Lives Matter,” to much applause from the broader internet. Now people from all sorts of fandoms are tweeting joke hexes at the president, because it’s simply another thing they’ve decided to do. People with no obvious relation to any one of these fandoms are copying them. Unfortunately, it might soon be another de facto way to respond to a tweet from someone you don’t particularly like.

[Read: Why K-pop fans are no longer posting about K-pop]

And though filling up Trump’s Twitter replies with hexes may have been meant as dark internet ribbing, some people have taken the hexes seriously. The internet personality and prominent QAnon conspiracy theorist Samantha Marika told her 230,000 Twitter followers that these “satanic comments” were evidence of a “spiritual war.” Other pro-Trump Twitter users are trying to banish the demons in the replies—exorcism by all-caps tweet (“WE REBUKE THIS DEMON. AMEN FATHER ?”). Even on 4chan, the longtime home of internet hoaxes and pranks ranging from unsettling to dangerous, a thread on the politics board /pol/ demands an explanation of what’s going on. The top reply is “Trump is literally battling satanists, reply Jesus is King to ruin their death spell,” so more than a hundred of the comments are just “Jesus is King.”

It’s understandable that the hexes would be bewildering to the casual onlooker. Fan culture is indecipherable by design, meant to be understood only by its participants, even though now it is highly visible to all sorts of people. This culture’s tactics are so mainstream that we’ve reached a point when some people are sincerely trying to un-hex the president of the United States, in response to a bunch of self-styled witches who are saying ominous stuff to him in languages they almost certainly don’t speak, paired with images of, for example, a waxy Joe Biden with tiny arms growing out of his face. As if now weren’t a confusing enough time to be online.