At some point, I realized that almost every project I worked on followed the exact same ritual. I would push code to GitHub, GitHub would trigger a CI pipeline, the CI runner would pull the code again, and finally, the production server would pull the same code from GitHub once more.

The more I thought about it, the more redundant it felt. I was effectively using GitHub as a middleman to move code between machines that I already owned and controlled.

Around that time, I came across a YouTube video by Tsoding. It fundamentally changed how I thought about Git. The video made me step back and ask a question that now feels obvious. Why am I pushing code to GitHub just so my own server can pull it back?

In my setup, I already had everything required to make this work directly. I had an SSH-accessible Linux server, Git installed everywhere it needed to be, full control over users and permissions, and all the usual Linux primitives like systemd, cron, and Git hooks available to automate things.

In this tutorial, I’ll walk you through how and why I run my entire Git and CI/CD workflow without GitHub by turning my own server into a first-class Git server.

I’ve been running this setup in production, and it has simplified both my mental model and my deployment pipeline far more than I initially expected.

What I had in this setup

- Ubuntu 22.04 LTS server

- SSH access to the server

- Git installed on both the client and the server

Remember: Git already thinks in terms of servers

One thing many people miss, and I missed this for a long time too, is that Git was designed for distributed workflows from day one. When I run a command like:

git clone user@server:/srv/git/myapp.gitGit isn’t doing anything magical behind the scenes. It’s simply opening an SSH connection to the remote machine, running git-upload-pack there, and streaming objects back and forth over standard input and output.

That’s also why Git URLs look suspiciously like SSH paths because they are. Once I wrapped my head around this, GitHub suddenly felt a lot less mysterious.

In practice, it’s just an SSH server that runs Git commands, with a polished web UI and an access-control layer sitting on top. Once I internalized that mental model, the rest of Git’s behavior started to feel obvious.

Part 1: Turning your server into a git server

Let’s begin by setting up proper access first.

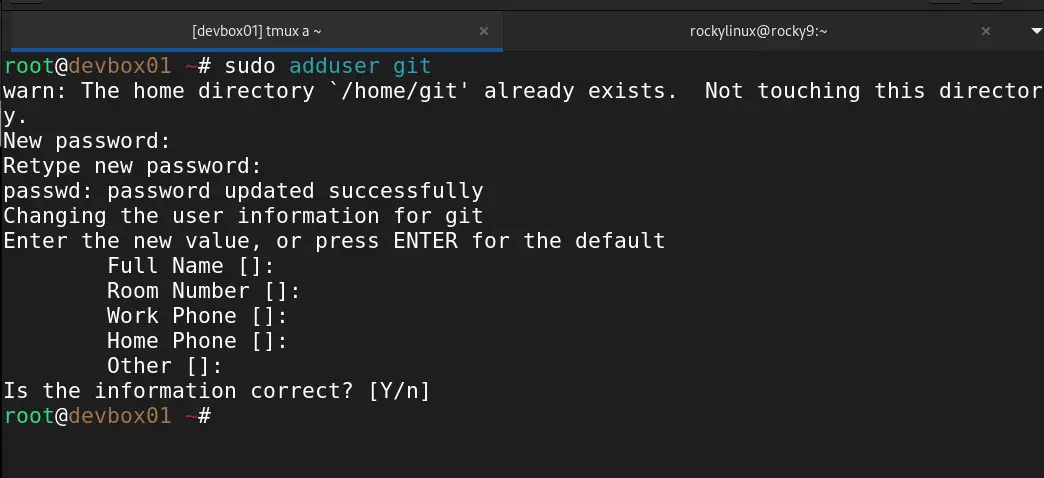

Sterp 1: Creating a Dedicated Git User

I always start by isolating Git access. On the server, I create a new dedicated user for git:

sudo adduser git

git user on the server for hosting repositoriesIn my setups, this user exists only to own repositories and handle Git operations. I usually disable shell access later to reduce the attack surface, especially on public-facing servers. Keeping Git activity scoped to a single, unprivileged user makes permission management and future hardening much easier.

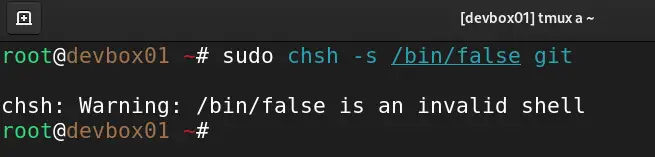

On most systems, I simply change the login shell to nologin:

sudo chsh -s /usr/sbin/nologin gitOn some distros, the path may be slightly different:

sudo chsh -s /bin/false git

git userAt this point, the git user can no longer get an interactive shell, but SSH-based Git operations continue to work normally.

To confirm, I usually try an SSH login.

Step 2: Adding SSH access

Before you can log in as the git user, you need to add our SSH public key generated on your client machine to git user’s authorized_keys file. For this, open the file and copy and paste the public key.

sudo vim /home/git/.ssh/authorized_keysNow you can ssh as the git user.

sudo git@demo-labYou should see something like:

This account is currently not available

git user For easier ssh access, instead of typing the server IP every time, I’ve set up .ssh/config on my client machine that looks something like this:

demo-lab alias in SSH config for quick server accessThat’s exactly what I want on a public-facing server. Git activity stays scoped to a single, unprivileged user, and there’s no easy way to turn that SSH access into a full shell.

Step 3: Creating a bare repository

When I’m setting up a Git server, I always use bare repositories. Servers don’t need a working tree, only the Git data itself. On the server, I create a central location for repositories and initialize one in bare mode:

mkdir -p /srv/git

cd /srv/git

git init --bare myapp.git

/srv/git/ on the Linux serverThat’s all it takes. At this point, the server is already capable of hosting Git repositories.

From here on, Git access is nothing more than SSH access. There are no tokens to manage, no OAuth flows, and no browser logins involved. In my experience, this simplicity is one of Git’s biggest strengths and why self-hosted Git over SSH remains so reliable and easy to secure.

Part 2: Pushing code directly to your server

On my local machine, I point Git directly at the server by adding it as a remote:

git remote add production git@demo-lab:/srv/git/myapp.git

git push production master

production remote after resolving safe directory restrictionThat’s usually the moment people pause and say, “Wait, that’s it?” And yes!! It really is.

Did you notice some error message on the first try of git push production master? This usually comes when git users don’t have permission to read from the remote repository. For this, the fix is simple. Assign permission using the chown command:

sudo chown -R git:git /srv/git/myapp.git

Git allows you to run scripts on the server when certain events happen. For deployments, the most useful one is the post-receive hook, which runs automatically after a push completes. Inside the bare repository on the server, I move into the hooks directory and create the hook file:

cd /srv/git/myapp.git/hooks

vim post-receiveHere’s a simple example I’ve used for lightweight deployments. Feel free to adjust APP_DIR and GIT_DIR variables as per your project.

#!/usr/bin/bash

APP_DIR=/var/www/myapp

GIT_DIR=/srv/git/myapp.git

while read oldrev newrev ref; do

if [[ "$ref" =~ .*/master$ ]]; then

echo "Master ref received. Deploying master branch to production..."

git

--work-tree=$APP_DIR

--git-dir=$GIT_DIR

checkout -f

else

echo "Ref $ref successfully received. Doing nothing: only the master branch may be deployed on this server."

fi

done

# systemctl restart myapp.service

📋

I’ve intentionally commented out the last line in the script. I’ll talk more on it in the upcoming section.

Finally, make this script (or git-hook) executable via the following chmod command:

chmod +x ./post-receiveFrom this point on, every git push to the server triggers the hook automatically. The code is pulled (or cloned on first run), and the service is restarted without any external CI system involved. In setups where I want something simple, predictable, and fully under my control, this approach works remarkably well.

Part 3: Simple yet automated CI/CD in action

To demonstrate the CI/CD in action, let’s clone the bare repository on the server to /var/www/myapp.

cd /var/www/

sudo root

git clone /srv/git/myapp.git myappYou might get a warning like this:

fatal: detected dubious ownership in repository at '/srv/git/myapp.git'To get rid of it, run this command:

git config --global --add safe.directory /srv/git/myapp.git

From the client machine, make some changes to the project (I had on my SSH client machine), create a new commit and now push to the remote repo and see if changes are being picked up automatically in /var/www/myapp project.

What I actually observed in practice

After switching to this model, the benefits showed up almost immediately. Deployments were noticeably faster because there was no round-trip through GitHub or a third-party CI service. When something failed, debugging was simpler. Thanks to the logs stored on the same machine, I wasn’t jumping between dashboards trying to reconstruct what happened.

I also gained full control over the execution order. Every command ran exactly when and where I expected it to, and no external outages could suddenly block my pipeline. From my experience, reliability matters more than fancy features.

More importantly, the mental model became dramatically simpler: push -> deploy. There were no YAML DSLs to maintain, no runners to troubleshoot, and no access tokens. Just Git doing what it’s always done, moving code from one machine to another.

Multi-developer workflow without GitHub

The first objection I usually hear is, “But what about collaboration?” That was my concern too at first, but in practice, it turned out to be straightforward.

I handle access entirely over SSH. Each developer either gets their own Linux account or, more commonly, a restricted SSH key tied to the shared git user. In ~git/.ssh/authorized_keys, I lock keys down like this:

command="git-shell -c "$SSH_ORIGINAL_COMMAND"",no-port-forwarding,no-X11-forwarding ssh-ed25519 AAAA...

This setup gives developers Git access only with no shell, no port forwarding, and no lateral movement on the server. From my experience, this strikes a good balance between usability and security on public-facing systems.

Branching works exactly the same as it does with GitHub. Developers can push feature branches or main branches normally:

git push production feature-x

git push production main

On the server side, hooks can enforce rules just like a hosted platform. I’ve used them to reject direct pushes to main, enforce naming conventions, and even run tests before accepting code.