Approximately infinity years ago, in a 2006 TED talk, the computer scientist Jeff Han demonstrated a new kind of touch-driven display. First, he wiggled all 10 fingertips against a big screen attached to a drafting desk, and then the display responded to all of them at once, as if he were scratching the belly of a puppy instead of operating a computer. During the 10 minutes that followed, Han demoed then-futuristic uses for the device: Heating and sculpting a molten-ore model, zooming and moving photographs as if on a light table, typing on a virtual keyboard, controlling a hand-drawn puppet. “I really think this is going to change the way we interact with machines from this point on,” Han said.

Two years later, in 2008, CNN’s John King manipulated a version of Han’s screen on Election Night. Dubbed the “Magic Wall,” the device allowed King to tap and zoom in and out of U.S. states, narrating a historic outcome: As county after county’s results filled in the blanks of previously Republican states such as Florida, Ohio, Iowa, and North Carolina, John McCain had no path to victory. Barack Obama would become the 44th president of the United States.

Something monumental had happened between these two events. After Han’s 2006 demo and before King’s 2008 broadcast, Steve Jobs introduced similar multi-touch technology in a much smaller package. He called it the iPhone.

This new device, all glassy and rounded, would take some time to find ubiquity—the year of his election, Obama (and many of the rest of us) were still using devices such as the RIM BlackBerry and Palm Treo to text and email on the go. The leap we took, from old-school cellphone to iPhone, was akin to swapping out a typewriter for a computer. The appeal of the new device was obvious: You could manifest a screen from your purse or pocket at any moment, pinching to zoom in on faces in photos or bistros on maps, swiping right for love or lust, flicking upward into the abyss of infinite scroll.

This week, John King was still stationed at his Magic Wall, meticulously explaining the startling shifts in support for Donald Trump in Florida’s Miami-Dade and Duval Counties, flicking back and forth between 2016 and 2020 to illustrate the change. And the thing is, it looked quaint. The Magic Wall was just a big, dumb iPad, offering no closure.

[Anne Applebaum: Trump’s forever campaign is just getting started]

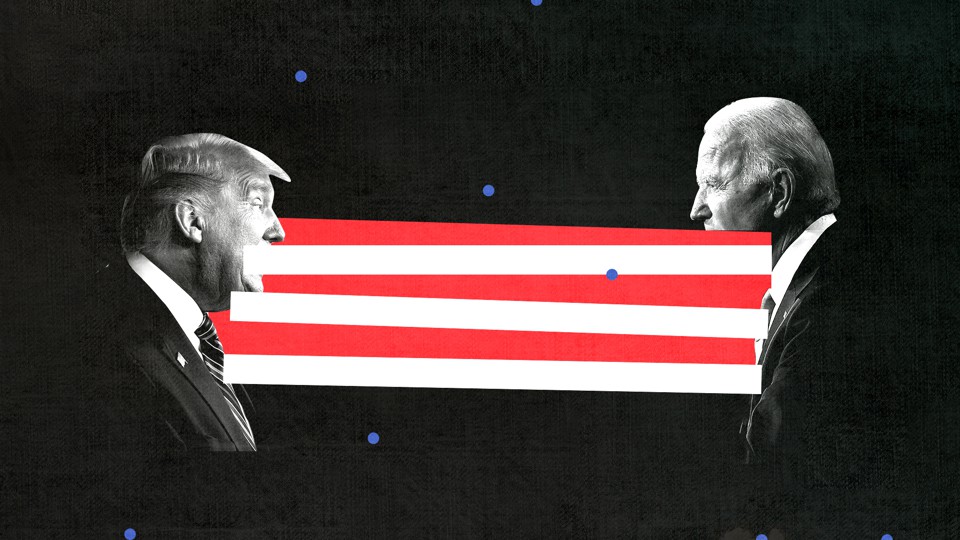

Not that closure is a thing anymore. Here we are with no concrete sense of who the next president of the United States will be. The pandemic had already tied this election in knots months earlier. The previously simple, if sometimes inconvenient, act of filing into the local school or church polling place had suddenly become dangerous, even potentially deadly.

Yet we all knew that chaos would be this election’s attendant. We knew to expect malfeasance from the president himself, including his hamstringing of the U.S. Postal Service and his spreading of dangerous lies about election fraud. But from there things got irredeemably, irreducibly boring: mere consequences of bureaucracy and its burping exhaust, election laws dictating when Wisconsin could start counting early ballots versus Florida. It’s as if the election has become an endless but depthless hall of mirrors.

Even in the past several hours, as clarity appeared to arrive, it didn’t take the neat and tidy form of county results comparable to prior races. The visual grammar of election-return maps broke down entirely, details like the percentage of precincts reporting having become meaningless now that massive mounds of absentee votes were being counted separately from automated polling-machine ballots. Twelve years after King’s first Magic Wall performance, state and even county results are pinch-zoomable from the couch or toilet.

But now they ask more questions than they answer. If you are extremely online, you may find that election outcomes, already slippery because of razor-thin margins, have become more like calculus problems. If about 28,000 ballots were outstanding in Pima County, Arizona, at 8 o’clock Thursday night, and 13,000 of them went to Biden, and 14,000 of them went to Trump, then that means a net gain of 1,000 for Trump … but how much of an advantage does that give the president? Better keep scrolling, in vain, for answers.

[Read: Fox News failed the test]

Americans swapped televisions for smartphones years ago, seeking news, or intimacy, from Facebook or Twitter instead. That shift hollowed out the local newspapers that might otherwise have offered greater local context, and it amplified the spread of misinformation that has characterized politicking for almost a decade. But it also exploded the slow sureness of knowledge into the wild shrapnel of the web.

And so, here we all are, days after Election Day, still drilling down into maps, most people pretending they understand more than they do, swiping madly through tweets, everyone an armchair John King, but narrating ourselves into new depths of anxiety instead of comprehension.

The pandemic only amplified that urge, moving all office work—all schooling, shopping, socializing—online, for safety. “We have so much technology these days,” Jeff Han said in front of his big touchscreen in 2006, “these interfaces should start conforming to us.” But technology always does the opposite. It is a vessel into which human society pours itself, the shape forming a mold that dictates what its people think. At least we’re all together in here, I suppose, amid this moment of chaos—swiping and staring, tapping and scrolling, until the tools that liberated America finally devour us.