Illustrations by Charlotte Fos

A blush-colored square filled with the all-caps advice SHOW UP EVERY DAY FOR SOMETHING YOU BELIEVE IN belongs to one of the least remarkable categories of Instagram content: visually unchallenging, impossible to disagree with, pink. Even if people do not exactly know how to show up every day for something they believe in—particularly during a pandemic—the basic spirit of the message is blandly uplifting for a millisecond during a bleary-eyed morning scroll through the feed: Today, I will, in some way, demonstrate that I believe in something, somehow! Hardly anything about it would dissuade the casual follower from double-tapping her appreciation before moving on.

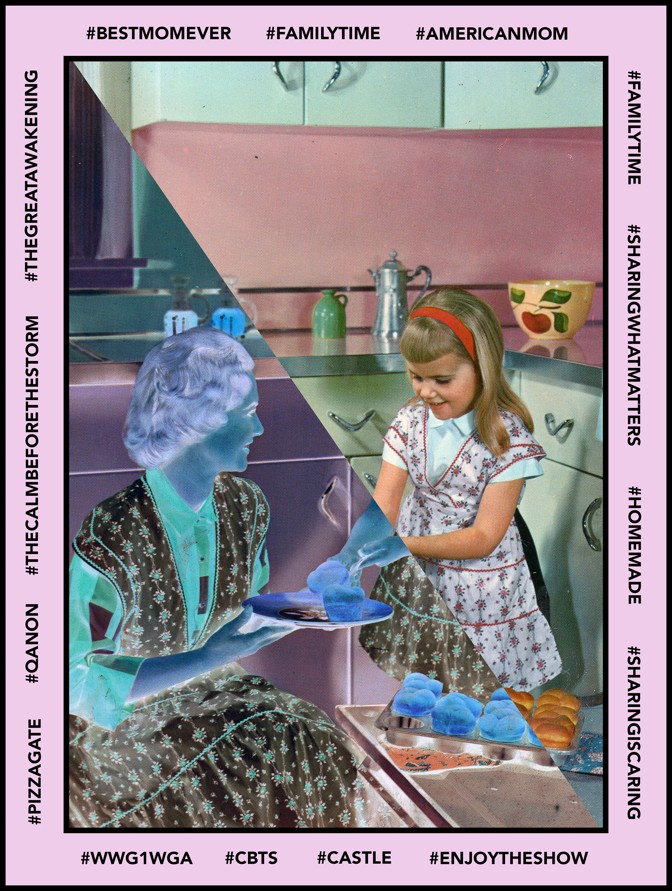

But this particular image, posted in March by the Utah-based fashion, beauty, and parenting influencer Jalynn Schroeder to more than 50,000 followers, is accompanied by a series of hashtags that includes the initialism WWG1WGA—“Where we go one, we go all”—a motto used by adherents of the QAnon conspiracy theory. QAnon is flexible and convoluted, but generally posits that President Donald Trump is locked in a battle with the “deep state,” and is attempting to bring down a ring of pedophiles and child traffickers that counts various high-profile politicians and celebrities as co-conspirators. Most famously, it’s the evolution of Pizzagate, the conspiracy theory that motivated a man to storm into a Washington, D.C., pizza restaurant with an AR-15 in December 2016, bent on exposing a supposed pedophilia ring in its basement, which did not exist.

When Schroeder’s feed nods to Q, it does so subtly, mostly in her stories and captions. On the grid, she posts photos of her manicures, her graphic tees, her favorite gummy vitamins, and the mommy-and-me sundresses she and her young daughter wear. She is also candid about mental health and the effects that giving birth can have on the body; recently, her followers have watched her prepare for and undergo surgery to correct an abdominal separation.

14-minute video she posted in March. It begins with the Maya Angelou quote “We are only as blind as we want to be,” written in funky orange and teal fonts. Wearing her curly purple hair in a cheetah-print headband, eyes made wider with electric-blue makeup, she then recounts watching an Instagram video sent to her by a friend, which she initially dismissed as “crazy”—but something was bothering her, and as the weeks went on, she decided to start her own research into QAnon and the global child-trafficking ring it seeks to expose. “I’m a mama of two, I have a lot of mamas following me, and this stuff has been very, very, very hard for me to digest,” she says. But she’s grateful she’s been led to the truth. “I’ve never felt more peace.”

The comments on this video are strikingly similar to those that appear on her regular posts: “So true,” with three heart emoji; “Proud of you for using your platform,” with three sets of clapping hands. In the caption, she links to a tutorial for mimicking her makeup.

In June, my colleague Adrienne LaFrance published a cover story on the rise of QAnon, writing that it had “made its way onto every major social and commercial platform and any number of fringe sites.” Instagram, famous for aspiration and tranquil luxury, has become a home for paranoid thinking just like everywhere else online: Influencers are mixing virulent distrust of the media and religious gratitude toward QAnon with sponsored posts for cool-girl clothing brands and beauty products. Many seem to be drawn in at first by concerns about child trafficking—a real and fairly noncontroversial problem that looks much different in practice than in the Q imagination, which has weaponized it. In July, a wild claim—that the furniture-retail site Wayfair was serving as a middleman for the child-trafficking ring that captivates QAnon devotees—took off, in particular among Instagram influencers whose accounts trade in the domestic and in the joys of consumer culture.

The anonymous Instagram account @little.miss.patriot shared its first post on June 29—about the supposed references to QAnon in the music video for Justin Bieber’s song “Yummy”—and went from 50,000 followers in early July to 266,000 by the time of this writing. Each of the posts from the self-proclaimed “truth seeker” and “digital soldier” uses a pastel-and-mustard color palette drawn from the past five years of Millennial-oriented direct-to-consumer beauty-brand marketing, sometimes accented with glitter or watercolor flourishes. The text on these backgrounds unfurls complicated conspiracy theories about Chrissy Teigen, Tom Hanks, Taylor Swift, and John F. Kennedy. “The deep state is evil and Satanic,” read white letters on soft pink and teal. “They are the ones controlling the media. it involves celebrities, too. the deep state is responsible for the trafficking of children & putting them into sex slavery. they torture these children & use their blood for a drug they all feast on, called adrenochrome. LOOK IT UP IF YOU DON’T KNOW.” In the comments, an influencer who designs children’s birthday parties shouts, “AMEN SIS.” Her grid is full of peach-tinted family photos and remodeled bedrooms, and Story Highlights are labeled “pregnancy,” “play,” “design,” “playroom,” and then “woke”—pink slides dotted with stars, detailing the way the media have ignored a “global elite pedophile ring” in favor of covering the pandemic.

Instagram has long been a place where what you see might be smoke and mirrors—a home for the best and most beautiful version of everyday life, put on display for consumption and then expensive imitation. What is startling about QAnon’s new presence there is the way it slips in: easily, and with little visible pushback from the influencers’ communities or from the platform that hosts them. We’re used to conspiracy theories appearing on the internet’s strange and ugly spaces, laid out with blurry photos and eyesore annotations. But those visual cues are missing this time. There’s no warning—just a warm, glamorous facade, and then the rabbit hole.

In the course of reporting this story, I contacted a dozen of the women posting about QAnon or related conspiracy theories on their accounts, as well as more than 60 of the women who had commented on their posts in support (with hearts, prayer hands, or emphatic thank-yous), many of whom had followings of their own in the tens of thousands. Very few responded, and most of those who did were hostile, stating that the use of their name or photos in a story was grounds for a lawsuit, or expressing a deep disdain for and distrust of the media—a core tenet of the QAnon belief system, as well as a somewhat common feeling among internet personalities who have successfully created their own large platforms.

Those who did agree to answer questions were concerned about child trafficking, but didn’t have extensive knowledge of QAnon, or seemed unaware that the people they were following were its proponents. Lana Michele, a Florida-based fashion and parenting influencer with 84,000 followers, agreed to speak briefly with me. Michele doesn’t post about QAnon, but she’d commented in support of a post about child trafficking that was shared by a woman who has a QAnon hashtag in her Instagram bio. “We are all just ‘waking up,’” Michele told me, adding that she’s been following conversations about child trafficking on Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok. “It is literally everywhere right now … and everyone needs to be aware, in my opinion.” She isn’t worried about the involvement of QAnon followers in the co

nversation. Any help in spreading the message is good help. “I find it useful,” she said.

Claire Thibault, an aspiring lifestyle blogger from North Carolina, had commented on the same post. “I’ve read and seen things about child trafficking only recently, and it’s disturbed me enough that I believe it should be mentioned more in the media,” she told me, saying that she first heard about the issue via fashion and lifestyle influencers. She cited as her primary information sources three Instagram accounts, one of which shares conspiracy theories almost exclusively and posts regularly about QAnon and Pizzagate. When I asked how she felt about those subjects, she said, “I honestly don’t know anything about either of those.”

[Read: Instagram is the internet’s new home for hate]

Two others told me that even though they themselves don’t believe in Q, they believe in the right to express oneself online. Ashley Houston, a mom from California who gained most of her 23,000 followers after she started making elegant pastel infographics about child trafficking, has never commented on QAnon or any other conspiracy theories—she prefers primary sources and clear, verifiable facts. Still, she’s friendly with some women who do post about those topics. “It’s okay for their focus to be on what they think is important,” she said. Michelle Merenda, a New Jersey–based parenting and mental-health blogger with 11,000 followers, told me she finds most of her information about child trafficking through hashtags. She listed several mainstream tags, including #saveourchildren, then added, “I do go to #QAnon, also #pedogate, #Pizzagate. And I know a lot of those things are conspiracy theories, but … there’s a lot of [questions posted there] that I would consider something that I would ask, and would kind of want to look into.”

Though Facebook, which owns Instagram, removed some QAnon-related content in May, conspiracism is still flourishing on the platform, largely untouched—especially in private QAnon groups, whose total membership is reportedly in the millions—despite more substantial recent actions from other social-media giants such as Twitter and TikTok. (Reddit is further ahead than all of them, having implemented a blanket ban against QAnon nearly two years ago.)

Instagram offers two main pathways for discovering QAnon, and neither has been slowed down in any way. The first is the hashtag search, which makes millions of posts about QAnon incredibly easy to access in one convenient feed. The second is the recommendations algorithm, which pushes followers from one account to the next, linking accounts that post similar content and have similar sets of followers. Reached for comment, an Instagram spokesperson said, “We are constantly reviewing our policies to ensure they reflect the latest in online behaviors, and to make sure we are keeping people safe on Instagram.”

However Facebook decides to do that, it’s clear that QAnon isn’t just hovering on the edges of Instagram—it’s increasingly part of the platform’s mainstream culture. Its supporters are so enthusiastic, and so active online, that their participation levels resemble stan Twitter more than they do any typical political movement. QAnon has its own merch, its own microcelebrities, and a spirit of digital evangelism that requires constant posting. One QAnon Instagram account I followed for this article gained 20,000 followers over three days in July. Nearly 2 million Instagram posts include the hashtag #WWG1WGA, and more than 800,000 are accompanied by the related tag #TheGreatAwakening. A recent post from the influencer Maddie Thompson uses the latter, along with the QAnon tag #painiscoming. The comments are full of hearts, kissy-face emoji, and gushing compliments: “Love that pure heart of yours!!” QAnon’s digital community represents something like a “social-media cheat code” for up-and-coming influencers, says Travis View, who has been documenting the rise of QAnon for the past two years on his podcast, QAnon Anonymous. “There is a large population of QAnon followers who will adore basically anyone who will acknowledge them or cater to their views in any way.”

Doing so is also less risky than it might have been a few years ago. Though Instagram influencers in the lifestyle and parenting spaces used to steer clear of politics and contentious social issues, appealing instead to the broadest audience possible, trends have shifted in the past few years toward more “authentic” content—open discussion about the challenges of motherhood, the strangeness of existing in a body, the right to speak one’s mind. For the many influencers who have spent years building intimate relationships with their audience, all this candor has served to make these bonds only tighter. And if followers can trust these women on domestic matters of interior design and party planning and postpartum depression and family emergency, maybe they can trust them on darker, more political issues as well.

[Read: How a fake baby is born]

When I showed some of these Instagram accounts to Sophie Bishop, a lecturer in digital humanities at King’s College London, she identified in all of them a “very recognizable,” feminine-coded aesthetic. “It’s aspirational, and then it’s also authentic enough to allow for relatability,” she told me. All kinds of influencers strive to make that sort of impression, but it can also help launder disinformation and dangerous ideas: “The original function of influencers was to be more relatable than mainstream media,” Bishop said. “They’re supposed to be presenting something that’s more authentic or more trustworthy or more embedded in reality.”

Taylor Lorenz wrote for The Atlantic early last year that Instagram is “likely where the next great battle against misinformation will be fought, and yet it has largely escaped scrutiny.” One of the most obvious explanations for that lapse is that Instagram—more than any other major social platform—shows each of its users exactly what they want to see. It’s a habitual, ritualistic space where people (like me) go for examples of how to be happy and well liked; it’s also where we take the chaos of our daily existence and push it into a simple, pleasing form we think other people will appreciate.

[Read: The coronavirus conspiracy boom]

Time spent there is reciprocal, a never-ending exchange of sweet words and the heart icons that are the only possible way to instantly respond to a piece of content on the platform. Instagram is women’s work, as it demands skills they’ve historically been compelled to excel at: presenting as lovely, presenting as desirable, presenting as good, safe, nonthreatening. All of which, of course, are valuable appearances for a dangerous conspiracy theory to have. Ironically, following many of the QAnon hobbyists will lead to a suggestion from Instagram that you follow Chrissy Teigen, one of QAnon’s designated villains, who also happens to have created a brand based on a desirable domestic life. The platform itself is operating on its interpretation of beautiful surfaces, and far less so on what the people producing them are saying.

“It’s a huge misconception that disinformation and conspiracy theorizing happens only in fringe spaces, or dark corners of the internet,” Becca Lewis, a Stanford doctoral student specializing in online political subcultures, told me. “We say you ‘fall down a rabbit hole.’ But it’s not how the ecosystem actually works. So much of this content is being disseminated by super popular accounts with absolutely mainstream aesthetics.”

Previously, Lewis had studied white-supremacist internet personalities who use similar tactics. She found that they would make Instagram accounts completely free of extremist rhetoric, and dedicated instead to dreamy engagemen

t photos and romantic vacations. Then they’d draw followers over to YouTube, where they would tell personal stories—particularly difficult to fact-check, always prefaced with a polite “Do your own research”—about how they’d come to believe in various white-nationalist, far-right causes, and conspiracy theories. She thinks what’s happening on Instagram looks similar.

“If you’re able to make this covetable, beautiful aesthetic and then attach these conspiracy theories to it, that normalizes the conspiracy theories in a very specific way that Instagram is particularly good for,” Lewis said. Of course, she added, it’s hard to say what’s orchestrated and what’s genuine on Instagram. But the effect is the same, whether or not it’s deliberate.

One account I followed in the course of reporting this story startled me more than the others. It looked like something I would stumble across and follow organically on any ordinary day, lost in the never-ending rush of images of the enviable lives of other people. @indyblue_ has an affiliate link to Rihanna’s lingerie line in her bio and seems to spend her days on the edges of mountain lakes or biking through the desert with her bleach-blonde husband, eating berries, wearing clothes she designed herself that read I LOVE YOU SAY IT BACK.

In her Instagram stories, she writes about the media “gaslighting” women by referring to conspiracy theories as what they are. When I messaged her for this story, she responded, asking, “Do you think I’m dumb[,] stupid[,] or dumb.”

If anything, I felt like an idiot. An aesthetic that appeals to me personally was being used to mask something that it’s my job to pluck out and pin to the wall: It made me shiver. My years using Instagram as a guide for how to look and how to live have trained me to see cool clothes and well-constructed personal brands as signifiers of something intrinsically good. I’ve curated my feed by hand; the thousands of images I look at each day are ones I have in some way chosen. They’re as much of who I am as any bulleted list of my dreams or desires would be. Why wouldn’t I trust them?