Editor’s Note: This article is part of “Uncharted,” a series about the world we’re leaving behind, and the one being remade by the pandemic.

Lucy Honeychurch grew up at Windy Corner, a comfortable estate in a polite enclave outside London. It was pleasant in the way suburbs always are: The neighbors were friendly, and the environment, free from the noise and grime of the city, was perfect for children. Her father, who had built the house, took pride in situating his family amid “the best society obtainable.”

But Honeychurch found the people dull and their aspirations banal. The neighbors were pleasant, but their “identical interests and identical foes,” as she put it, became suffocating. Suburbia, she concluded, was actually a horror.

Honeychurch might as well be a Millennial Brooklynite media professional prepping for the launch of negroni season at the local gastropub, or an activist shaking her fist at local NIMBYs opposed to denser, transit-and-biking-friendly infill development. But no, she is the protagonist in E. M. Forster’s 1908 novel, A Room With a View, a biting critique of Edwardian English life, including the drab boredom of suburbia.

By the time Forster was writing, people had been mocking the suburbs for centuries. In the late middle ages, the agrarian and mercantile peasants of the European suburbium were mostly seen as underclasses to the urban gentry. The 18th-century London neighborhoods of Marylebone, Mayfair, and others continued that tradition. In 1897, the martians of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds began their wrath there, on the outskirts, where life was deemed so wretched as to earn even the extraterrestrials’ first strike. That scorn persisted: “Little boxes, all the same,” went a popular Malvina Reynolds song about cookie-cutter homes in 1962. The same sneer perseveres today.

[Read: A defense of the suburbs]

And yet, people have always loved suburban life. U.S. cities have been growing at their edges for a century and a half. Country living of the Windy Corner sort evolved into the “streetcar suburbs” of the early 20th century, offering a comfortable life just a carriage ride from town. After World War II, mass-developed subdivisions followed, compelled by a housing crisis and emboldened by racist government-housing subsidies, white flight, and the sheer size of the North American continent. Like pornography, you know a suburb when you see it: large expanses of low-slung buildings, where residences are separated from commerce, where industry is mostly absent, where family life thrives inside detached homes that stipple meandering streets flanked by lawns and dotted with mailboxes. More than half of Americans, 175 million of us, live in communities like these now, most for the same reasons as our forebears.

Or we live in a slightly more urban version of them, because now, everywhere is the suburbs. Eighty-four percent of Americans live in cities, but most of them don’t live in the dense, modernist urban spaces that the name conjures—places like New York or Hong Kong. Instead, they occupy the greater metropolitan areas of Houston or Atlanta or Denver, which extend far beyond the city limits. All told, roughly three-quarters of the population live in single-family homes, a reminder that even the urban cores of big American cities, such as Dallas or Phoenix, wear the trappings of suburbia.

For decades, urbanists have sought to end America’s long marriage to sprawl. The architects Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson have identified characteristics of suburban form worthy of retrofitting, including the dominance of low-density buildings, an emphasis on private spaces instead of public ones, the reliance on single-use rather than mixed-use zoning, an almost complete dependence on the automobile, and dead-end roads that make street networks less useful.

But after the anxious spring of 2020, these defects seem like new luxuries. There was always comfort to be found in a big house on a plot of land that’s your own. The relief is even more soothing with a pandemic bearing down on you. And as the novel coronavirus graduates from acute terror to long-term malaise, urbanites are trapped in small apartments with little or no outdoor space, reliant on mass transit that now seems less like a public service and more like a rolling petri dish. Meanwhile, suburbanites have protected their families amid the solace of sprawling homes on large, private plots, separated from the neighbors, and reachable only by the safety of private cars. Sheltered from the virus in their many bedrooms, they sleep soundly, dreaming the American dream with new confidence.

Safety has always warmed the suburban soul. The American dream is sometimes equated with property ownership and the nuclear families such properties house—but really, they are just hulls for a more fundamental suburban aspiration: individualism, which the suburban home demarcates and then protects.

“The American dream was Every man gets his castle,” Todd Gannon, the head of architecture at Ohio State University’s Knowlton School, told me. Above all else, the suburban life is one of independence, a self-contained homestead where the American family can realize its desire and potential, unperturbed by others. Even the family car gets its own bedroom.

This independence was always mythical, in part. The tax base that suburbia generates often can’t support the infrastructure required to sustain it—roads, sewers, schools, emergency services, and all the rest. Along with federally backed mortgages and mortgage-interest deductions, the suburban lifestyle amounts to an enormous government subsidy, or else it slowly decays into disrepair.

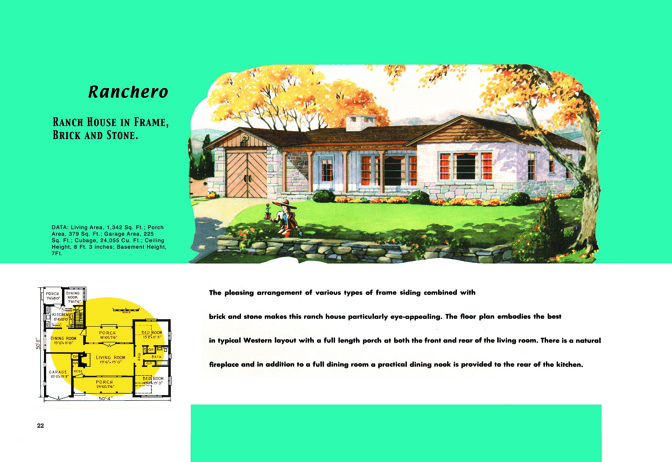

Suburbia makes the illusion of self-sufficiency material. Even the architectural design most strongly associated with it, the American ranch home, borrowed its name and style from a fantasy of autonomy. Broad and rambling, the ranch transforms the real western ranchero into a set of symbols: of wide, open spaces offering opportunity; of a family in charge of the land and therefore its own fate; even of the good breeding of livestock, now transformed into the rearing of children.

When the American dream is framed as independence rather than communalism, the benefits of city life start to seem like detriments instead. In urban environments, for example, walkability connects people to local commerce—something single-use residential zoning eschews in favor of car trips. That’s why the architect Andrés Duany, who also co-founded Congress for the New Urbanism, has likened single-family residential communities to an “unmade omelet,” wherein the eggs, cheese, and vegetables represent homes, work, and commerce that are unnaturally separated from one another. Mixed-use development, by contrast, offers shops, restaurants, and offices within a stone’s throw of apartments and condos.

But rejecting mixed-use planning has made suburban communities unexpectedly resilient in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s not so appealing to be able to walk to the corner café for brunch (a cooked omelet, presumably) when the venue has been shut down by shelter-in-place orders. Even as restaurants and retailers reopen, dining in or shopping has been degraded by the corona

virus: Restaurant occupancy is restricted by social distancing; establishments are struggling to make ends meet; and worries about contamination in enclosed, air-conditioned spaces damage the experience. All of that might return to normal eventually, but by the time it does, the gastropubs and ice-cream parlors may have gone under anyway. The coffee shops may convert for good into tableless pickup stands. Commercial catastrophe will affect the allure of existing mixed-use developments far more than single-use, low-density residential communities, which never relied on those benefits as a condition of residency.

The pandemic will improve suburban life, perhaps in lasting ways. Take the automobile commute: The exodus from the office has dramatically decreased traffic and pollution, a trend that will continue in some form if even a fraction of the people who abandoned their commutes continue to work from home. Dunham-Jones, who is also my colleague in Georgia Tech’s college of design, thinks that even a modest rise in telecommuting could also increase the appeal of local walking and bike trips. Families have two cars, but nowhere to go. They are rediscovering the pleasures of pedestrianism.

That doesn’t mean suburbanites want the density of urban life, however. Some fear it, blaming the spread of the virus on tightly packed, metropolitan masses. Those fears mistake crowding for density. Some of the worst coronavirus hot spots have erupted not in dense cities, but in crowded communities such as nursing homes, Hasidic households, and manufacturing plants. Very dense global cities like Seoul and Singapore have controlled the virus effectively. Meanwhile, in the New York City area, early infection rates were higher in certain suburbs.

But America is not South Korea or Singapore. Americans have been running away from dense, vertical design for a century. Those who already prefer sparse, low-slung living will likely use their fear of COVID-19 to entrench their preference.

[Read: The unfinished suburbs of America]

At the very least, the interior design of their homes might change in a post-pandemic world. The ranch house might seem natural to many Americans, but it was designed for a wholly different era. Starting in the 1930s, the ranch was cobbled together from a motley crew of unlikely sources and inspirations. Its interiors combined the minimalism of European high modernism (which was influenced by another outbreak, tuberculosis) with the Spanish ranchos and the tamed naturalism of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose Usonian home designs and vision for a suburban utopia exalted individualism at communal scale.

Ranches often fused dining and living areas together, a design that would evolve into the now-ubiquitous great room. But their interior design also borrowed some of the visual and symbolic trappings of the dude ranch—all that wood paneling in bedrooms and dens, on kitchen cabinets, or in the exposed rafters of cathedral ceilings. Even the barbecue grill was adapted in part from the western ranch, built into a kitchen or patio in some early California designs.

Conveniences like grills offer more reasons to enjoy staying home. The modern, electric residence, with its refrigerator and dishwasher and washing machine and the like, helped consolidate activities that previously required outside contact, such as laundry or daily milk delivery, into efforts pursued in the home. Those devices anchored gender norms and invented ever more new labor to fill the time saved—but they also reinforced the inclination of realizing ever more needs and desires at home. A new gadget or appliance (and space to house it) produced an even greater sense of self-sufficiency—and more reason to seek out more space, and more gadgets. Suburban houses keep growing in part because they internalize more and more public amenities.

Now homeowners are outfitting their private enclaves further, with backyard vacation spots and luxurious pool resorts, unsure how long the coronavirus threat will persist. Chest freezers have sold out too, as consumers with room to house them seek to become better prepared in case future viral surges press them back inside. Threats of meat shortages due to supply problems and outbreaks at meatpacking plants made freezers feel newly essential. (Poetically, they also renew the American ranch home’s historical connection to the actual ranch, where cattle and therefore beef were plentiful.) Those with the means, space, and cultural proclivity to do so might make food stockpiling a mainstream practice, rather than a fringe neurosis for the paranoid. In the late 1990s, the old cellar evolved into the suburban wine room, a luxury replacing a necessity. Now it might yet devolve back into the second pantry, an unlikely marriage between the 17th century and the 21st. We’re all homesteaders now.

That’s just the start of the mutations COVID-19 will impose on residential interiors, mostly for the better. Americans were already coming to regret their ubiquitous open-floor plans, which put everyone in the same shared space. But before the pandemic, at least parents were going to work and kids to school during the day. Now we’re home with our families all the time—and, thanks to video meetings, our teachers, friends, and colleagues too. “We’ve all retreated to our domestic quarters, but we’ve dragged everyone along with us,” Gannon said. When I spoke with him, Gannon had been working from his 2,700-square-foot, 1950s ranch home for two months already, having awkwardly converted its open living room into two makeshift offices. Everywhere, the Zoom meetings are constant, and there’s not enough quiet, private, and appropriate rooms or spaces from which to conduct those videoconferences. Suburbs aren’t also called “bedroom communities” for nothing.

To make up for the shortfall of specialized rooms, homes with lots of divided spaces might be best equipped for the coronavirus quarantine. Simple designs common to large, suburban homes, such as bedrooms with their own en suite bathrooms, suddenly simulate the privacy of an apartment block. And for those lucky enough to have them, extra bedrooms can be converted to offices or workspaces. During the outbreak, a big house is best.

American homes are extravagant, having swelled from about 1,500 square feet on average in 1973 to more than 2,400 in 2018. After the pandemic, memory of the novel utility of all that space could justify even more of it. Some companies have already declared their intention to let workers telecommute forever, and real-estate analysts anticipate more companies eliminating or curtailing expensive commercial leases to save money. If more workplaces offer even some of those benefits, the appeal (and potential tax deduction) of home-office space, among others, might make big, suburban homes even more desirable. His-and-hers walk-in closets are already common, along with separate master bathrooms. As development evolves, his-and-hers offices might appear in new builds or as retrofits in existing homes.

ms even more desirable. (Getty)

The existing suburban McMansion might find a new life in the aftermath of the pandemic too. Although critics have deemed these homes aesthetically ghastly, inefficient, and extravagant, many families want the additional space of a suburban monstrosity to accommodate extended family, such as parents or grandparents. Multigenerational living might become even more common as the coronavirus threat and its economic consequences wear on. Colleges are still sorting out whether and how students will return to campus in the fall, and beyond. And recent graduates unable to find jobs, or unwilling to move to them, might return home for indeterminate periods of time. The exurban castle offers lots of space at an affordable price, thanks to its distance from the city.

Multigenerational households represent a modest increase in density, and they can make quarantine more tolerable on top of it. The summer is upon us, but camps are largely closed and ordinary family activities have been substantially disrupted. The spring lockdowns also proved that working from home while facilitating children’s remote schoolwork is extremely challenging. Intergenerational households offer more hands and eyes to watch the kids or manage mealtimes made incompatible by overlapping schedules. Schools have always been a huge driver of residential real-estate sales, and even a modest increase in online learning could shock the market. Economic pressure may encourage consolidation of some families into bigger but more populous single-family homes, while decoupling home values from school districts even somewhat could make them more affordable.

Other compromises between urban and suburban life are possible. The trend to allow accessory dwelling units (a city planner’s name for backyard apartments) offers some privacy and outdoor space while increasing density and lowering housing costs. Medium-density multifamily apartments have proved resilient, too. Dunham-Jones lives in a retrofit factory in Inman Park, Atlanta’s first suburb (now right in the center of the city). Her building is small, with 30-some units scattered across several buildings, all of which open directly to the outdoors. More efficient and walkable than suburban living, arrangements like this are less dense but more contagion-resistant than the wood-framed, podium-building apartment complexes that have erupted all over the country as city life became more appealing, particularly among Millennials.

Those apartment buildings, which sometimes contain hundreds of individual units, were creating management difficulties even before the pandemic. The increase in Amazon, Instacart, DoorDash, and other deliveries already had made safe access—not to mention package storage and collection—difficult. The coronavirus has worsened matters, multiplying deliveries and their associated foot traffic while making common areas like elevators and hallways more dangerous. Retrofitting these buildings for social distance is difficult, if not impossible.

Their amenities, such as social halls and swimming pools, are suddenly far less attractive than they were mere months ago, too. Who wants to pay a premium for benefits you can’t, or don’t feel comfortable, using? When the threat eventually lifts, Dunham-Jones reasons, Millennials will still want to live urban lives. But memory of the coronavirus era may color their future preferences.

Duany, the New Urbanism pioneer, has already started reimagining residential space along those lines. Speaking virtually at the Congress for the New Urbanism conference this month, he advanced initial ideas for a townhome design after the coronavirus. It eliminates the first-floor retail space, expands the “token” balcony into a two-story terrace, and introduces dedicated, per-unit delivery sheds. The townhome merges laundry into a larger lean-up room near the entry, enlarges the pantry for stockpiling, and adds a “flex room,” a nod to the new demand for schoolrooms, home offices, and other activities imported from the formerly normal world without.

Duany’s design is entirely hypothetical—an exercise more than an earnest proposal. But real housing stock might establish new trends immediately. Some smaller condo and townhome developments are already changing in response to the pandemic. Brian Davison, the managing partner of Minerva, a residential real-estate developer in Atlanta, told me that he’s started considering adjustments to projects under development this spring. He calculated that his firm would spend $12,000 per unit for amenities at one property, such as a common gym. “Will people use it?” he wondered, “or should I buy everyone a Peloton for their unit instead?” It’s still early days for post-pandemic real-estate development, but the more multifamily housing developments move communal benefits into private residences, the more like suburbia they will become.

The suburbs were never as bad as their stereotypes. The little boxes might have been all the same, but the ’50s suburban plots also flowed continuously into one another, with unobstructed front and backyards, forming unified communities. And those communities were in some ways far less homogeneous than their legacy recalls, even despite the scourge of redlining and its serious, long-term effects.

In her book Houses for a New World, the architectural historian Barbara Miller Lane documents the earliest suburbanites’ diversity and their strong sense of community. They were largely low-income, working-class people, with a majority of skilled and unskilled workers mixing with white-collar managers, secretaries, and the self-employed. These communities were absolutely segregated and largely white, but that meant something different in 1950 than it does today: The suburbs became new melting pots of ethnic and religious diversity that has since coalesced in America. Catholics and Presbyterians and Lutherans and Jews lived in proximate harmony, and likewise Italians, the Irish, Poles, Norwegians, and Lithuanians. But despite the structural racism that founded these communities, a devotion to property ownership did create a strong sense of loyalty among their residents, which persisted over generations. The black and brown people who did move there just wanted to live a life. It’s a catastrophe that they were so often excluded from the opportunity—not that the opportunity existed in the first place.

Over time, the comforts of single-family life reached fewer and fewer Americans. Almost a century later, redlining has locked black and Hispanic families out of the generational wealth of housing. Wages remain flat for blue-collar and unskilled jobs regardless of race or ethnicity, and the suburbs have become a new center of poverty in America, its infrastructure unable to sustain lesser means. Ultimately, affluence facilitates many of the benefits suburbia offers during the pandemic—it’s the difference between being able to benefit from Instacart delivery thanks to a work-at-home office job and working that grocery-delivery job yourself.

[Read: The unfulfilled promise of fair housing]

The privileges of space and self-sufficiency evaporate without the resources to pursue them. The suburbanites who already have (and, if their white-collar jobs are safe, can keep) their castles might not care to think much about those who don’t have one, anchoring the status quo in deeper waters. “If you can hunker down and not suffer,” Gannon told me, “you’ll have less empathy for those wh

o can’t.”

During previous economic calamities, the government altered housing policy, establishing the Federal Housing Administration in 1934 to regulate mortgages after the banking crisis. After World War II, the FHA encouraged commercial mass development to ease the housing crisis, and after the 2008 recession, the federal government bailed out mortgage banks, mitigated some foreclosures, and introduced homebuyer tax incentives. All of these efforts affirmed the ongoing reign of single-family, suburban-style homes. It’s too early to know if a similar federal intervention for the coronavirus recession might arrive. If it does, there’s no reason to believe that aid would suddenly underwrite dense, modern urbanism. American life has been suburban for a century, and it’s a mistake to see suburbia as an historical aberration waiting to collapse.

That makes the suburbs aspirational, despite all their downsides. The European-modernist retort to their appeal, about which many domestic urbanists fantasize, is more collectivism. But the American response redoubles its bet on individualism: to socialize the ability to hunker down safely and comfortably, whether from plague or any other threat. There are plenty of them, after all. When pandemic worries got sidelined for protests over antiblack police violence, some reformers called on governments to defund the police and reinvest their budgets elsewhere. The New York City Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who supports the idea, was asked how such a society might work. Her answer: “It looks like a suburb.”