Before Reddit, before GitHub, and even before the World Wide Web went online, there was Usenet.

This decentralized network of discussion groups was a main line of communication of the early internet – ideas were exchanged, debates raged, research conducted, and friendships formed.

For those of us who experienced it, Usenet was more than just a communication tool; it was a community, a center of innovation, and a proving ground for the ideas.

📋

Oldest network that is still in use

Usenet is one of the oldest computer network communications systems still in widespread use. It went online in 1980, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University.

1980 is significant in that it was pre-World Wide Web by over a decade. In fact, the “Internet” was basically a network of privately owned ARPANet sites. Usenet was created to be the network for the general public – before the general public even had access to the Internet. I see Usenet as the first social network.

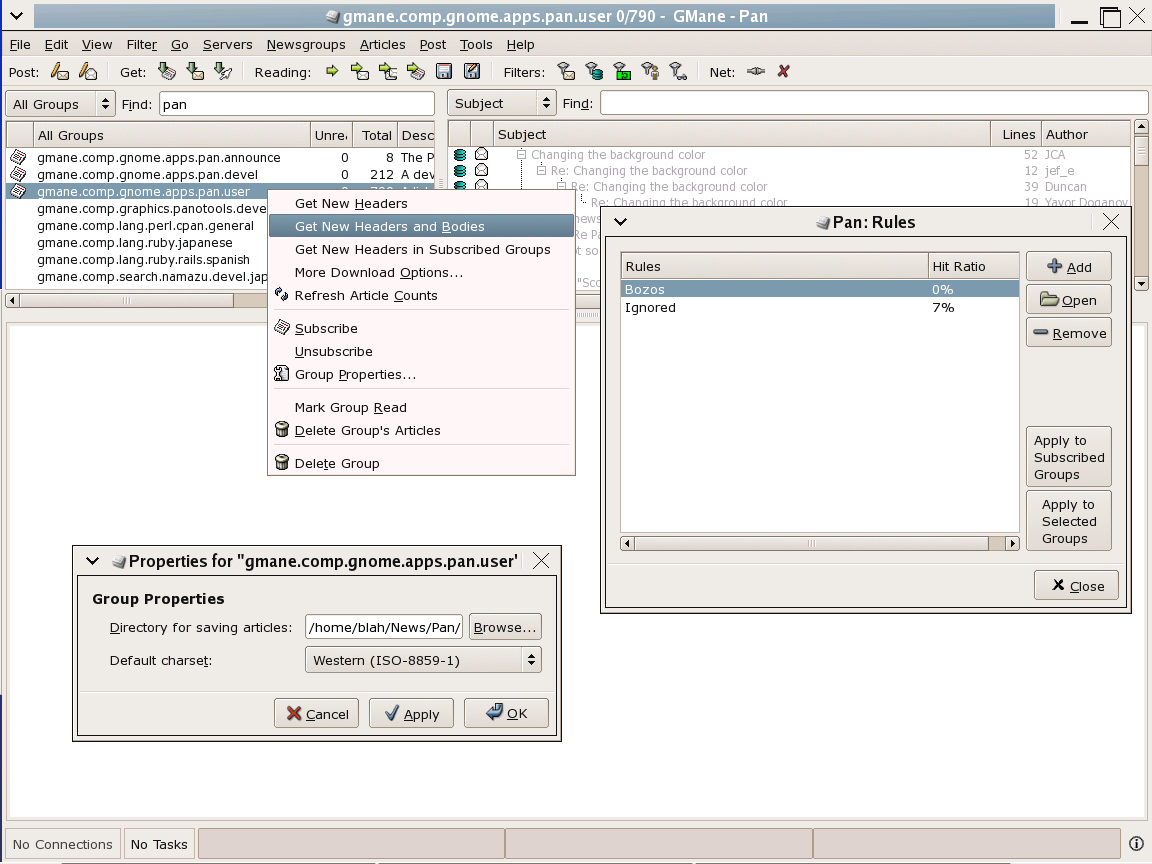

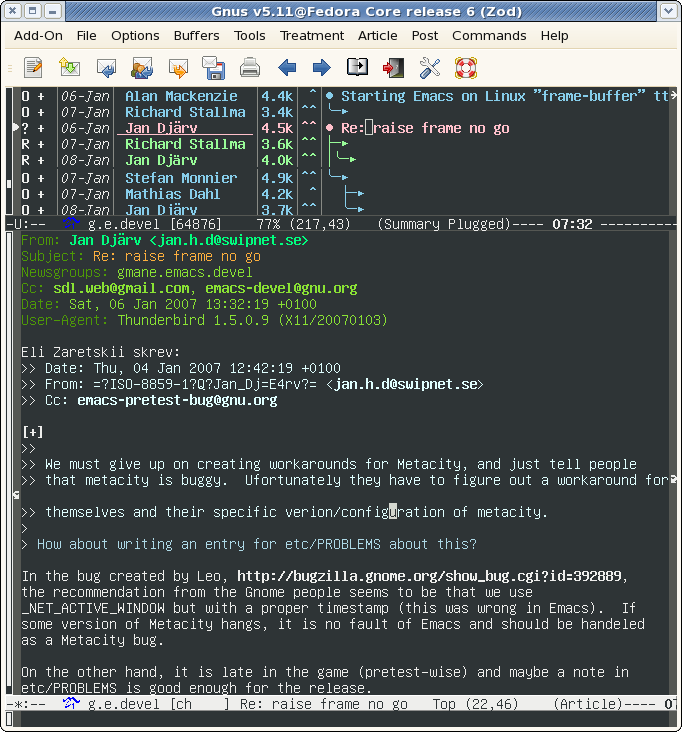

Over time, Usenet grew to include thousands of discussion groups (called newsgroups) and millions of users. Users read and write posts, called articles, using software called a newsreader.

In the 1990s, early Web browsers and email programs often had a built-in newsreader. Topics were many; if you could imagine a topic, there was probably a group made for it and, if a group didn’t exist, one could be made.

The culture of Usenet: Learning the ropes

While I say that Usenet was the first social network, it was never really organized to be one. Each group owner could – and usually did – set their own rules.

Before participating in discussions, it was common advice to “lurk” for a while – read the group without posting – to learn the rules, norms, and tone of the community. Every Usenet group had its own etiquette, usually unwritten, and failing to follow it could lead to a “flaming.” These public scoldings, were often harsh, but they reinforced the importance of respecting the group’s culture.

For groups like comp.std.doc and comp.text, lurking was essential to understand the technical depth and specificity of the conversations. Jumping in without preparation wasn’t just risky – it was almost a rite of passage to survive the initial corrections from seasoned members. Yet, once you earned their respect, you became part of a tightly knit network of expertise and camaraderie – you belonged.

Usenet and the birth of Linux

One newsgroup, comp.os.minix, became legendary when Linus Torvalds posted about a new project he was working on. In August 1991, Linus announced the creation of Linux, a hobby project of a free operating system.

Usenet’s structure – decentralized, threaded, and open – can be seen as the first demonstration of the values of open-source development. Anyone with a connection and a bit of technical know-how could hop on and join in a conversation. For developers, Usenet quickly became the main tool for keeping up with rapidly evolving programming languages, paradigms, and methodologies.

It’s not a stretch to see how Usenet also became an essential platform for code collaborating, bug tracking, and intellectual exchange – it thrived in this ecosystem.

The discussions were sometimes messy – flame wars and off-topic posts were common – but they were also authentic. Problems were solved not in isolation but through collective effort. Without Usenet, the early growth of Linux may well have been much slower.

A personal memory: Helping across continents

My own experience with Usenet wasn’t just about reading discussions or solving technical problems. It became a bridge to collaboration and friendship. I remember one particular interaction well: a Finnish academic working on her doctoral dissertation on documentation standards posted a query to a group I frequented. By chance, I had the information she needed.

At the time, I spent a lot of my time in groups like comp.std.doc and comp.text, where discussions about documentation standards and text processing were common. She was working with SGML standards, while I was more focused on HTML. Despite our different areas of expertise, Usenet made it easy for the two of us to connect and share knowledge. She later wrote back to say my input had helped her complete her dissertation.

This took place in the mid-1990s and that brief collaboration turned into a friendship that lasts to this day. Although we may go long periods without writing, we’ve always kept in touch. It’s evidence to how Usenet didn’t just encourage innovation but also created a lasting friendship across continents.

The decline and legacy of Usenet

As the internet evolved, Usenet’s use has been fading. The rise of web-based forums, social media, and version-control platforms like GitHub made Usenet feel clunky and outdated, and there are concerns that it is largely being used to send spam and conduct flame wars and binary (no text) exchanges.

On February 22, 2024, Google stopped Usenet support for these reasons. Users can no longer post or subscribe, or view new content. Historical content, before the cut-off date can be viewed, however.

This doesn’t mean that Usenet is dead; far from it. Giganews, Newsdemon, and Usenet are still running, if you are interested in looking into this. Both require a subscription, but Eternal September provides free access.

If Usenet’s use has been declining, then why look into it? Its archives. The archives hold detailed discussions, insights, questions and answers, and snippets of code – a good deal of which is still relevant to today’s software hurdles.

Conclusion

I would guess that, for those of us who were there, Usenet remains a nostalgic memory. It does for me. The quirks of its culture – from FAQs to “RTFM” responses – were part of its charm. It was chaotic, imperfect, and sometimes frustrating, but it was also a place where real work got done and real connections were made.

Looking back, my time on Usenet was one of the foundational chapters in my journey through technology. Helping a stranger across the globe complete a dissertation might seem like a small thing, but it’s emblematic of what Usenet stood for: collaboration without boundaries. It bears repeating: It was a place where knowledge was freely shared and where the seeds of ideas could grow into something great. And in this case, it helped create a friendship that continues to remind me of Usenet’s unique power to connect people.

As Linux fans, we owe a lot to Usenet. Without it, Linux might have remained a small hobby project instead of becoming the force of computing that it has become. So, the next time you’re diving into a Linux distro or collaborating on an open-source project, take a moment to appreciate the platform that helped make it all possible.