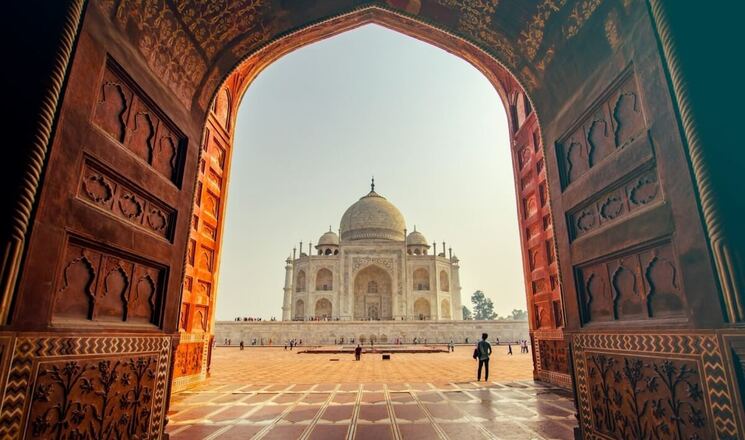

During a conference in Geneva, the member states of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) reached an agreement on a new treaty aimed at preventing the for-profit piracy of traditional knowledge. This treaty, called the Treaty on Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge, is intended to address the issue of “biopiracy,” where companies patent ideas taken from traditional knowledge. For example, a US company patented derivatives of the neem tree as pesticides, despite the fact that local communities in India were already aware of the plant’s properties. There have also been attempts to patent traditionally cultivated plant varieties such as basmati rice and jasmine rice.

The main objective of the new treaty is to ensure that patent applications disclose any involvement of traditional knowledge. At the conference, we provided advice on the treaty text to the Indigenous Caucus, member states, and advisors, and also gave presentations at side events. The final text of the treaty, although it includes some compromises, is a significant step towards protecting traditional knowledge after 24 years of deliberation.

International law already provides some protections for genetic resources and traditional knowledge through the 2010 Nagoya Protocol. However, this protocol does not cover patents, which is where the new treaty comes in. The treaty contains three key provisions on genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge.

The first provision requires patent applicants to disclose where the genetic resources came from. This could be places such as herbariums or gene banks. For patents based on traditional knowledge, applicants must disclose the Indigenous peoples and local communities who provided it. If this information is unknown, the applicant must disclose where they sourced it from. In cases where the applicant genuinely doesn’t know the source, they must declare this.

Patent officers are expected to provide guidance to help applicants meet the disclosure requirement and offer opportunities to rectify any failures to disclose. It’s important to note that this requirement does not apply retroactively to patents granted in the past.

During the treaty negotiations, there were debates about punitive measures for not disclosing, with some countries arguing that such measures would hinder innovation. A compromise was reached, and while the treaty does not allow patents to be revoked or made unenforceable for failure to disclose, it does allow for other sanctions and remedies if a patent holder has failed to disclose with fraudulent intent.

The treaty also allows states to establish information systems, such as databases, about genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge. These systems should be developed in consultation with Indigenous peoples, local communities, and other stakeholders. The information in these systems can be used by patent offices to determine whether patent applications are genuinely new or cover information that is already publicly available. However, the treaty does not specify who should own and control these systems, which is a shortcoming as it disregards the idea that Indigenous peoples should retain sovereignty over their own data.

During the conference, suggestions from the Indigenous Caucus were considered in the draft treaty text, but it needed endorsement from a member state to be included in the negotiations. This is seen as a flaw in the process since the treaty specifically relates to Indigenous peoples’ knowledge. The final treaty reflects compromises between WIPO member states, influenced by the Indigenous Caucus, industry bodies, and representatives of civil society.

In Australia, there have been patents related to traditional knowledge and uses of Kakadu plum, emu oil, and native tobacco. To address this issue, Australia’s government agency for intellectual property rights, IP Australia, has established an Indigenous Knowledge Initiative to improve the handling of Indigenous knowledge in the country’s intellectual property system. Australia played a significant role in the treaty negotiations, with an Australian delegate elected president of one of the main committees. The country also welcomed Indigenous participation in both informal and formal negotiations and supported the proposed text to protect traditional knowledge. Australia’s progress in protecting Indigenous knowledge will be influenced by future negotiations at WIPO, including determining the sanctions for breaching the patent disclosure requirement.