People don’t always need another human being to experience a sense of connection. The deep emotional bonds many people have with their pets proves this. (So might the popularity of the Pet Rock in the 1970s but that’s just speculation.) Even Link in The Legend of Zelda had an inanimate companion: his trusty sword (see Figure 9.1).

It’s also possible for people to feel that sense of connection in the context of behavior change without having direct relationships with others. By building your product in a way that mimics some of the characteristics of a person-to-person relationship, you can make it possible for your users to feel connected to it. It is possible to coax your users to fall at least a little bit in love with your products; if you don’t believe me, try to get an iPhone user to switch operating systems.

It’s not just about really liking a product (although you definitely want users to really like your product). With the right design elements, your users might embark on a meaningful bond with your technology, where they feel engaged in an ongoing, two-way relationship with an entity that understands something important about them, yet is recognizably non–human. This is a true emotional attachment that supplies at least some of the benefits of a human-to-human relationship. This type of connection can help your users engage more deeply and for a longer period of time with your product. And that should ultimately help them get closer to their behavior change goals.

Amp Up the Anthropomorphization

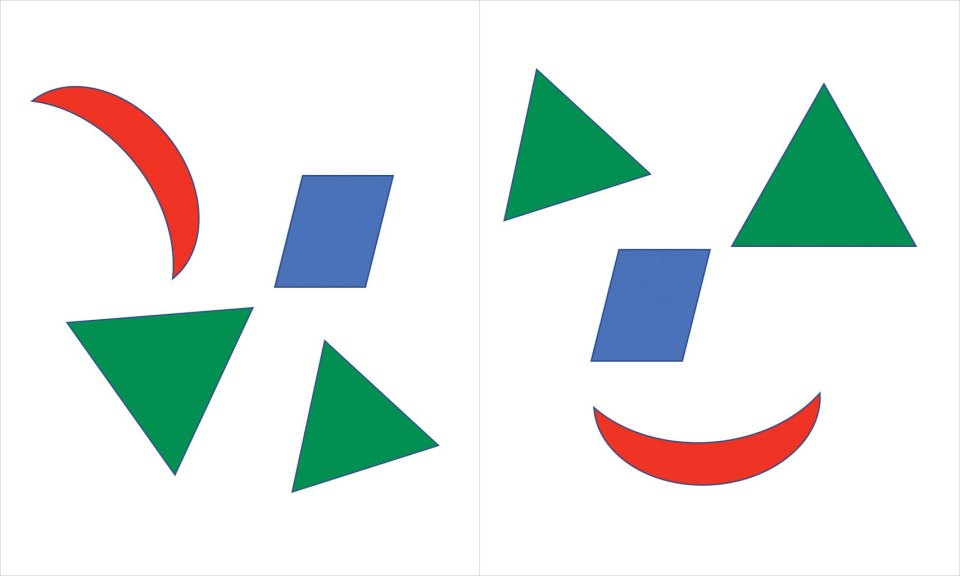

People can forge relationships with non–humans easily because of a process called anthropomorphization. To anthropomorphize something means to impose human characteristics on it. It’s what happens when you see a face in the array of shapes on the right side in Figure 9.2, or when you carry on an extended conversation with your cat.[1]

People will find the human qualities in shapes that slightly resemble a face, but you can help speed that process along by deliberately imbuing your product with physical or personality features that resemble people. Voice assistants like Siri, Cortana, and Alexa, for example, are easily perceived as human-like by users thanks to their ability to carry on a conversation much like a (somewhat single-minded) person.

Granted, almost nobody would mistake Alexa for a real person, but her human characteristics are pretty convincing. Some research suggests that children who grow up around these voice assistants may be less polite when asking for help, because they hear adults make demands of their devices without saying please or thank you. If you’re asking Siri for the weather report and there are little ones in earshot, consider adding the other magic words to your request.

So, if you want people to anthropomorphize your product, give it some human characteristics. Think names, avatars, a voice, or even something like a catchphrase. These details will put your users’ natural anthropomorphization tendencies into hyperdrive.

Everything Is Personal

One thing humans do well is personalization. You don’t treat your parent the same way you treat your spouse the same way you treat your boss. Each interaction is different based on the identity of the person you’re interacting with and the history you have with them. Technology can offer that same kind of individualized experience as another way to mimic people, with lots of other benefits.

Personalization is the Swiss Army Knife of the behavior change design toolkit. It can help you craft appropriate goals and milestones, deliver the right feedback at the right time, and offer users meaningful choices in context. It can also help forge an emotional connection between users and technology when it’s applied in a way that helps users feel seen and understood.

Some apps have lovely interfaces that let users select colors or background images or button placements for a “personalized” experience. While these types of features are nice, they don’t scratch the itch of belonging that true personalization does. When personalization works, it’s because it reflects something essential about the user back to them. That doesn’t mean it has to be incredibly deep, but it does need to be somewhat more meaningful than whether the user has a pink or green background on their home screen.

Personalized Preferences

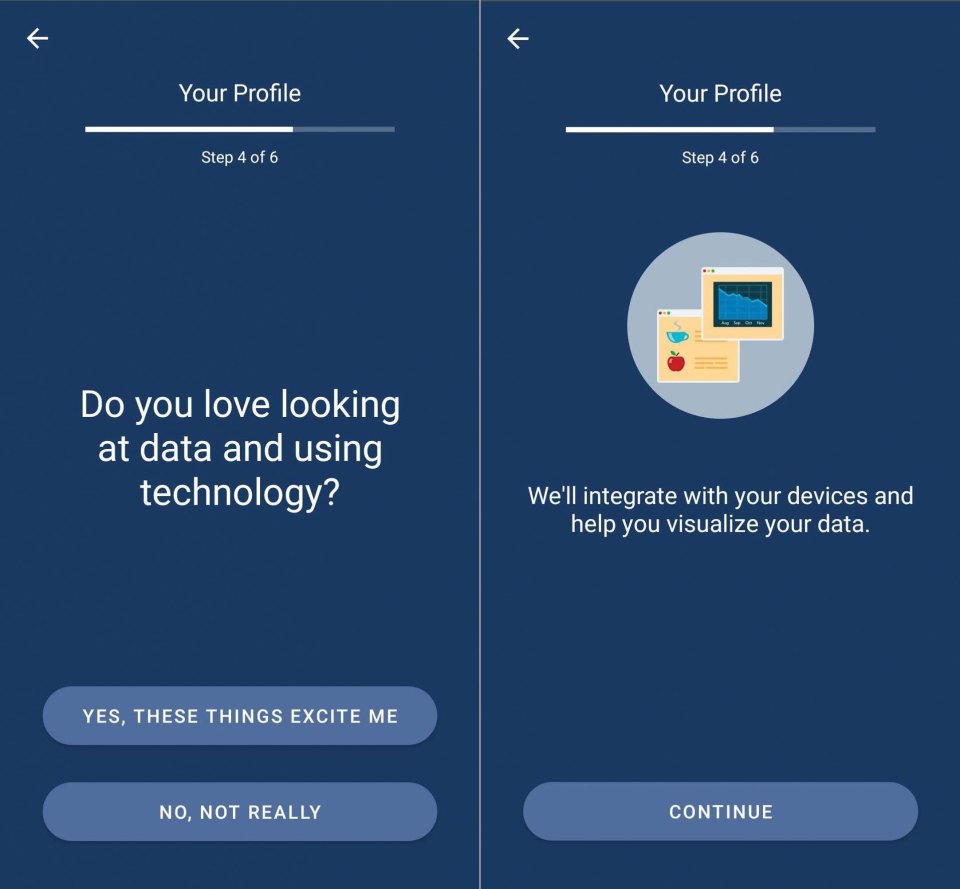

During onboarding or early in your users’ product experience, allow them to personalize preferences that will shape their experiences in meaningful ways (not just color schemes and dashboard configurations). For example, Fitbit asks people their preferred names, and then greets them periodically using their selection. Similarly, LoseIt asks users during setup if they enjoy using data and technology as part of their weight loss process (Figure 9.3). Users who say yes are given an opportunity to integrate trackers and other devices with the app; users who say no are funneled to a manual entry experience. The user experience changes to honor something individual about the user.

If you can, recall back to ancient times when Facebook introduced an algorithmic sort of posts in the newsfeed. Facebook users tend to be upset anytime there’s a dramatic change to the interface, but their frustration with this one has persisted, for one core reason: Facebook to this day reverts to its own sorting algorithm as a default, even if a user has selected to organize content by date instead. This repeated insistence on their preference over users’ makes it less likely that users will feel “seen” by Facebook.[2]

Personalized Recommendations

If you’ve ever shopped online, you’ve probably received personalized recommendations. Amazon is the quintessential example of a recommendation engine. Other commonly encountered personalized recommendations include Facebook’s “People You May Know” and Netflix’s “Top Picks for [Your Name Here].” These tools use algorithms that suggest new items based on data about what people have done in the past.

Recommendation engines can follow two basic models of personalization. The first one is based on products or items. Each item is tagged with certain attributes. For example, if you were building a workout recommendation engine, you might tag the item of “bicep curls” with “arm exercise,” “upper arm,” and “uses weights.” An algorithm might then select “triceps pulldowns” as a similar item to recommend, since it matches on those attributes. This type of recommendation algorithm says, “If you liked this item, you will like this similar item.”

The second personalization model is based on people. People who have attributes in common are identified by a similarity index. These similarity indices can include tens or hundreds of variables to precisely match people to others who are like them in key ways. Then the algorithm makes recommendations based on items that lookalike users have chosen. This recommendation algorithm says, “People like you liked these items.”

In reality, many of the more sophisticated recommendation engines (like Amazon’s) blend the two types of algorithms in a hybrid approach. And they’re effective. McKinsey estimates that 35% of what Amazon sells and 75% of what Netflix users watch are recommended by these engines.

Don’t Overwhelm

Sometimes what appear to be personalized recommendations can come from a much simpler sort of algorithm that doesn’t take an individual user’s preferences into account at all. These algorithms might just surface the suggestions that are most popular among all users, which isn’t always a terrible strategy. Some things are popular for a reason. Or recommendations could be made in a set order that doesn’t depend on user characteristics at all. This appears to be the case with the Fabulous behavior change app that offers users a series of challenges like “drink water,” “eat a healthy breakfast,” and “get morning exercise,” regardless of whether these behaviors are already part of their routine or not.

When recommendation algorithms work well, they can help people on the receiving end feel like their preferences and needs are understood. When I browse the playlists Spotify creates for me, I see several aspects of myself reflected. There’s a playlist with my favorite 90s alt-rock, one with current artists I like, and a third with some of my favorite 80s music (Figure 9.4). Amazon has a similar ability to successfully extrapolate what a person might like from their browsing and purchasing history. I was always amazed that even though I didn’t buy any of my kitchen utensils from Amazon, they somehow figured out that I have the red KitchenAid line.

A risk to this approach is that recommendations might become redundant as the database of items grows. Retail products are an easy example; for many items, once people have bought one, they likely don’t need another, but algorithms aren’t always smart enough to stop recommending similar purchases (see Figure 9.5). The same sort of repetition can happen with behavior change programs. There are only so many different ways to set reminders, for example, so at some point it’s a good idea to stop bombarding a user with suggestions on the topic.

Don’t Be Afraid to Learn

Data-driven personalization comes with another set of risks. The more you know about users, the more they expect you to provide relevant and accurate suggestions. Even the smartest technology will get things wrong sometimes. Give your users opportunities to point out if your product is off-base, and adjust accordingly. Not only will this improve your accuracy over time, but it will also reinforce your users’ feelings of being cared for.

Alfred was a recommendation app developed by Clever Sense to help people find new restaurants based on their own preferences, as well as input from their social networks. One of Alfred’s mechanisms for gathering data was to ask users to confirm which restaurants they liked from a list of possibilities (see Figure 9.6). Explicitly including training in the experience helped Alfred make better and better recommendations while also giving users the opportunity to chalk errors up to a need for more training.[3]

Having a mechanism for users to exclude some of their data from an algorithm can also be helpful. Amazon allows users to indicate which items in their purchase history should be ignored when making recommendations—a feature that comes in handy if you buy gifts for loved ones whose tastes are very different from yours.

On the flip side, deliberately throwing users a curve ball is a great way to learn more about their tastes and preferences. Over time, algorithms are likely to become more consistent as they get better at pattern matching. Adding the occasional mold-breaking suggestion can prevent boredom and better account for users’ quirks. Just because someone loves meditative yoga doesn’t mean they don’t also like going mountain biking once in a while, but most recommendation engines won’t learn that because they’ll be too busy recommending yoga videos and mindfulness exercises. Every now and then add something into the mix that users won’t expect. They’ll either reject it or give it a whirl; either way, your recommendation engine gets smarter.

Personalized Coaching

At some point, recommendations in the context of behavior change may become something more robust: an actual personalized plan of action. When recommendations grow out of the “you might also like” phase into “here’s a series of steps that should work for you,” they become a little more complicated. Once a group of personalized recommendations have some sort of cohesiveness to systematically guide a person toward a goal, it becomes coaching.

More deeply personalized coaching leads to more effective behavior change. One study by Dr. Vic Strecher, whom you met in Chapter 3, showed that the more a smoking cessation coaching plan was personalized, the more likely people were to successfully quit smoking. A follow-up study by Dr. Strecher’s team used fMRI technology to discover that when people read personalized information, it activates areas of their brain associated with the self (see Figure 9.7). That is, people perceive personalized information as self-relevant on a neurological level.

This is important because people are more likely to remember and act on relevant information. If you want people to do something, personalize the experience that shows them how.

From a practical perspective, personalized coaching also helps overcome a common barrier: People do not want to spend a lot of time reading content. If your program can provide only the most relevant items while leaving the generic stuff on the cutting room floor, you’ll offer more concise content that people may actually read.