Ubuntu and Launchpad use OpenPGP keys heavily. Each source package is signed with the uploader’s key, and binary and source package downloads from Ubuntu’s primary archives and from users’ Personal Package Archives (PPAs) are indirectly signed by the publisher process with per-archive keys of its own. Access to Launchpad’s bug-manipulation interface is also controlled by OpenPGP.

As a result, Launchpad needs a reliable key-storage and synchronization mechanism. For many years this backend was SKS, the Synchronizing Keyserver, which is written in OCaml and has its origins in a Ph.D. thesis that solved the problem of how to optimally synchronize collections of data such as OpenPGP keys.

SKS

For a long time the only major problem we had with SKS was its ability to handle load: it didn’t really have any. SKS can only process one request at a time, and this request handler is occupied some of the time by requests from the database synchronization process.

We mostly solved this problem by carefully configuring squid to cache end-user requests. We ran squid and SKS for many years in a dual-server configuration without many more problems.

Attacks on SKS

In the past few years, however, SKS has become more challenging to operate. Attacks on the keyserver network are increasingly common. These attacks typically work by adding single large packets or many small packets to a key, yielding a “poison key” that SKS has great difficulty in handling efficiently.

The SKS reconciliation process works by first exchanging information about the hash value of the entire content of each key. OpenPGP keys are structured in packets of various types. The hash value is made consistent between servers by each server processing a key’s packets in an agreed order when calculating the hash. Only after each side has determined which key hashes it doesn’t know about do they exchange the keys themselves, parse them, and extract and store the missing packets.

Since anyone can add material to any key and upload it to a member of the SKS network, it is difficult to detect and avoid such keys until it is too late. The receiving server must read, parse, and store the entire key so that the hash calculation will be correct on subsequent reconciliation attempts. And, as mentioned, SKS would have had to handle all of this, plus client traffic, with a single-threaded database backend. It didn’t handle it.

Response to SKS Attacks

After the advent of poison keys, we added another pair of SKS backends and reworked our frontends to divide requests between “known safe” requests that could be sent to one pair of backends, or “possibly unsafe” requests that would be sent to a separate sacrificial pair.

We also added a custom patch to SKS to ignore a particularly large and problematic poison key, but didn’t pursue this path very far. As well as the architectural and design problems mentioned earlier, SKS is written in OCaml, which none of the team were familiar with.

If the writing hadn’t already been on the wall for SKS in our infrastructure, it certainly was now.

Hockeypuck

We had been interested in replacing SKS for some time, and our preferred candidate was the very promising Hockeypuck keyserver, written by Casey Marshall (who, coincidentally, is now an engineering manager at Canonical). Hockeypuck promised to interoperate with SKS while offering the ability to handle more than one request at a time, and to use a database server instead of SKS’s in-process Berkeley DB.

A couple of early attempts to add Hockeypuck to our existing SKS infrastructure as a prelude to switching over completely failed due to various bugs in Hockeypuck. This was perhaps not surprising, as this was possibly the first time Hockeypuck had been used in anger.

The IS team at Canonical, along with Casey, found and fixed a number of bugs and we at last had a suitable replacement for SKS.

Deployment

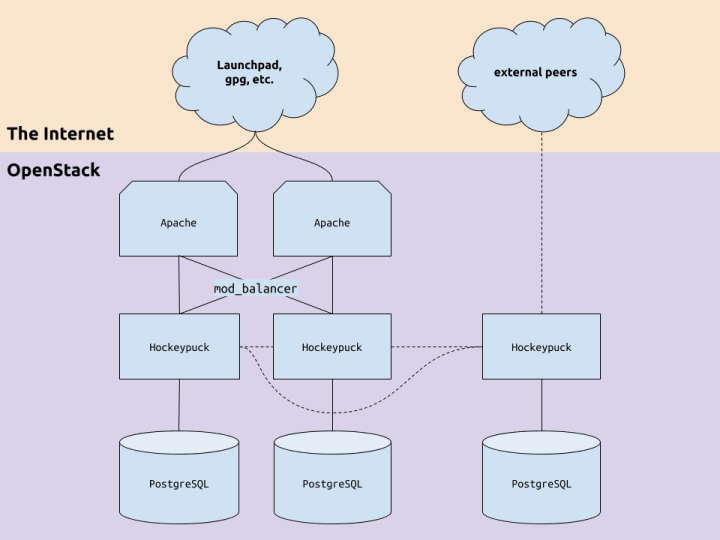

After some experimentation, we settled on the following deployment layout. Apache and PostgreSQL are deployed with their respective Juju charms, while Hockeypuck is running from its snap with strict confinement.

We initially deployed with a two-node PostgreSQL cluster, but after remembering that Hockeypuck itself handles replication for us, we redeployed with a set of single-node PostgreSQL instances.

Migration

We encountered a number of challenges performing the migration.

We quickly discovered that the environment in which we were planning to deploy hockeypuck was not optimized for the initial database load, mainly due to the available I/O bandwidth, although we estimated that it would be ample for ongoing load. However, importing a recent key dump directly into Hockeypuck took approximately 48 hours.

To work around this, we used a spare physical host with lots of RAM and performed the initial load operation with the source files and the PostgreSQL database entirely in memory, using tmpfs. This import took only four hours and yielded a database that we could dump quickly and restore in the deployment environment.

Restoring the PostgreSQL database dump in the target environment takes about 1.75 hours, with a further 3.5 hours to rebuild the prefix tree, an external data structure that is used during the reconciliation process. (The prefix tree is less than 300M on disk, but since it needs to be consistent with the database, it’s difficult to back up unless Hockeypuck is idle.)

Production

After running Hockeypuck in production for a few weeks, we noticed that it would occasionally consume memory until it ran out and crashed. Some more work from Casey squashed this bug.

There was also another key-poisoning incident, this time of FreePBX’s key, which was being refreshed very frequently by many clients. The load caused by requests for this key revealed that some earlier tuning of the PostgreSQL service to allow us to load key dumps directly allowed too many connections, which caused the database servers to OOM. We reconfigured PostgreSQL to be more suitable for the planned load.

We have now been running hockeypuck as our only keyserver for over six months and it has been stable and responsive.

Future

Following discussions with some folks in the keyserver community, Casey Marshall implemented a special mode in Hockeypuck that only returns self-signed packets in keys. While this yields a keyserver that isn’t very useful for a traditional web of trust, it’s sufficient for distributing keys that are only used to verify signatures, which is exactly Launchpad’s use case. We may explore replacing the existing cluster with a self-signed-only cluster in the future.