Memorial designs by Rael San Fratello, Refik Anadol Studio, and Sekou Cooke

Unlike a war, a pandemic is invisible and diffuse. It’s everywhere and nowhere. Its death toll is ultimately unknowable. That makes a virus difficult to mark with physical tributes. Few memorials mark the 1918 Spanish flu; one is a modest granite bench built in Vermont two years ago, underwritten by a local restaurant also marking its own centennial.

third wave of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths is lashing the nation from coast to coast. More than 12 million Americans have contracted COVID-19, and more than 250,000 of them have died. Early vaccine tests are promising, but a broad rollout is months away at minimum. Even after it wanes, the long-term effects of the virus could continue to debilitate people who have “recovered.”

So this might seem like a strange time to imagine memorializing the pandemic in a formal way. A premature time. Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial was conceived in 1981, six years after the United States had withdrawn from the conflict. Michael Arad and Peter Walker’s 9/11 memorial broke ground at the site of the World Trade Center in 2006, almost five years after the attacks.

But there are downsides to waiting. A traumatic event is an author of its own memorial; as a famous anecdote attests, when a Nazi soldier asked Pablo Picasso if he had made Guernica, the famous painting the artist created during the month following the Luftwaffe’s bombing of its Basque namesake in 1937, Picasso replied, “No, you did.” The feelings, facts, and ideas available during a calamity dissipate as it ebbs. The temptation arises to contain tragedy in a tidy box, closing the book on its history.

[Read: There are no nostalgic Nazi memorials]

Rather than await a design competition for a real memorial, we wanted to see, in the brutal heaviness of the moment, how some of the nation’s most exciting designers might memorialize this time. We commissioned three pieces from artists who straddle the lines between art and architecture, design and social justice, technology and manufacturing to speculate on the question What might a COVID-19 memorial be? These are the results.

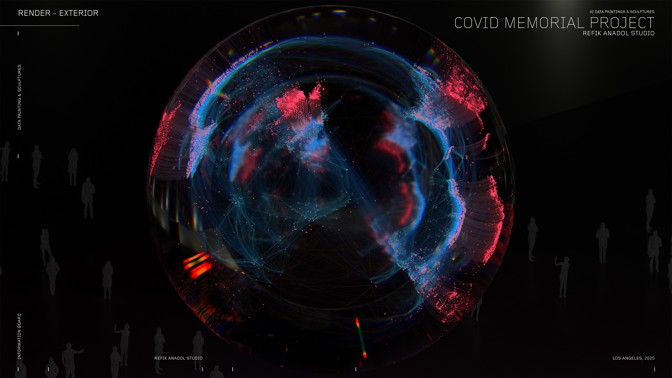

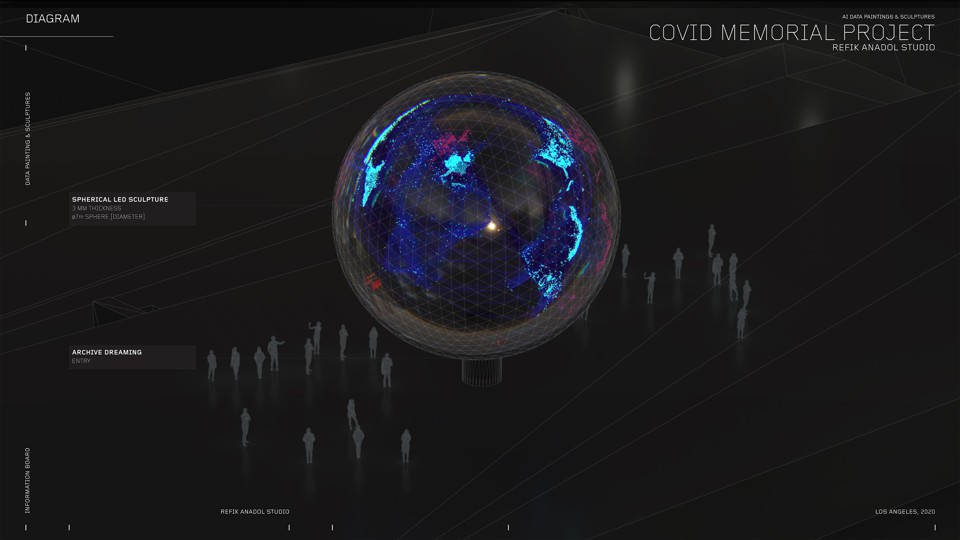

Refik Anadol Studio – Memory Globe

Refik ANadol believes a memorial should offer more than mere memory. It should also remind people how to be better. “We need to attract attention to something we should have done during COVID,” Anadol told me. “Reported better. And created an archive of data.”

Making people feel, rather than rationalize, about data has been Anadol’s calling card. “ISS Dreams,” for example, transforms millions of images taken from the International Space Station into flowing waves of sandy dunes, as if the Earth itself were just the granules of another world’s shifting desert.

So Anadol wanted a COVID-19 memorial to use data as a material. In a pandemic, the narrative is in the data, he told me. But COVID-19 data have been heterogeneous and hard to come by, covered in a constant mist of misinformation. That failure becomes the subject of the studio’s proposed memorial: After the pandemic ends, its visitors could visualize the virus’s journey.

To prototype the idea, Anadol and his colleagues aggregated and cleaned data from sources such as Johns Hopkins University and HealthMap, and then floated glowing representations of infections and deaths above their locations on a transparent globe. Pelin Kivrak, one of Anadol’s studio collaborators, reminds me that monuments become sites of pilgrimage. “People go to memorials not just to remember but also to feel a certain way,” she said.

In this case: small in the face of the virus’s destructive smallness. Anadol imagines an installation with a 20-foot sphere atop a smaller, cylindrical plinth, animating the virus’s growth over time with LED lights. Organic blobs of viral spread float in an atmosphere above the planet’s surface. The boundaries of countries and continents appear on the surface only when representations of infections and deaths rise above them, a stark reminder of how humankind activates and carries the virus. Where it dies out—the ultimate goal of pandemic management—the monument also erases any trace of its human carriers on Earth, who vanish back into their ordinary lives.

[Read: When do memorials help?]

It’s a fantasy, of course. The data aren’t good enough; the uncounted infections and excess deaths will be lost to history. The memorial would therefore mark not only SARS-CoV-2’s infected or dead human beings, but the political, infrastructural, and logistical blunders that made the pandemic so much worse than it might have been otherwise.

Anadol acknowledges that a memorial to the virus itself—not its victims—risks downplaying or even trivializing its impact. In response, he ponders the idea of a control room in its base for a single human operator, who might manipulate the timeline or zoom in on particular locations. It’s a reminder of how precious a truly centralized, shared repository of infection data might have been. Anadol also speculates that individuals could add their own photographic materials to the memorial.

But Kivrak is less apologetic about putting information rather than people at the center of the design. “When we talk about the Holocaust, it’s an ongoing problem. It doesn’t go away,” she says. A physical memorial honoring a hypothetical data standard for instantly sharing the spread of a deadly virus suggests a long-term function for the project: as a visualization of any future pandemic, via actual, live data-collection methods perfected after COVID-19 wanes. Many memorials invoke the promise never to forget. When it comes to pandemics, the best way to keep that promise would be to build an infrastructure that makes a repeat of this year impossible.

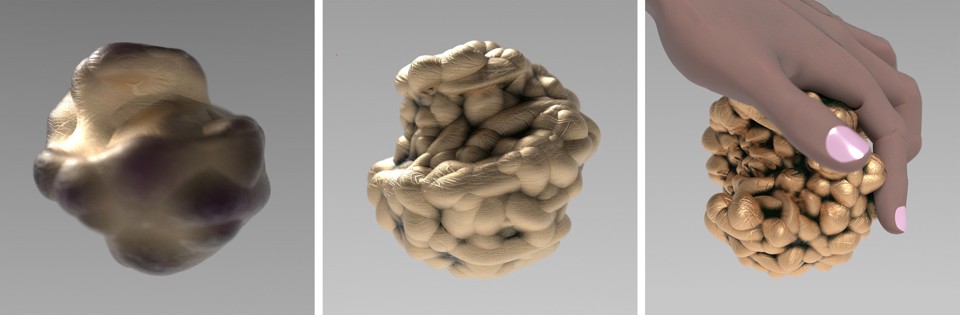

Rael San Fratello – 29CuCV-19

Ronald Rael distinctly remembers the smell of copper pennies, back when they were still made out of copper. “I later discovered that it’s not the smell of the metal itself,” he told me, “but of all the bodies that have touched the penny.” It’s disgusting, he admitted, but also alluring. You can’t help but touch it, smell it—even become tempted to taste it.

Rael San Fratello, the studio he and fellow artist and architect Virginia San Fratello started, thrives on repurposing such ordinary materials. In 2019, the pair installed three pink teeter-totters across the gaps in the border wall, offering Americans and Mexicans a literal fulcrum on which to balance their common humanity. Through their fabrication studio, the two also bring together novel and historical materials and construction practices, such as robot-extruded mud structures. “When we 3D print with coffee, chardonnay or curry, the objects we make are incredibly fragrant,” San Fratello says. “The scent of these otherwise ubiquitous designs gives them meaning.”

Quarantine has limited our ability to use smell and touch for communion, so she and Rael became interested in finding a way to replicate the experience. That’s where pennies come in: Copper is an antiviral—a quality with obvious symbolism in the moment—and one that evolves over time, developing a patina as it interacts with water and air. So the pair latched on to it as a material.

Rael San Fratello’s first idea was a pragmatic one: a traditional memorial made of copper molded into a bulbous, organic wall. The copper material would invite the touch lost to quarantine. Outdoors, it could develop a green or purple patina. “If touched constantly,” San Fratello said, “the patina might never occur, and the memorial will remain shiny.”

Even so, a wall etched with names feels like a mismatch for COVID-19. Whom, exactly, would such a monument include? “I feel like it’s too conventional,” Rael told me. It’s a symptom of memorialism more broadly. Memorials and monuments have to lure visitors, draw attention, inspire photographs, structure space. Unless they don’t. Perhaps, Rael and San Fratello concluded, a memorial could be distributed to the people instead. A thing that you could touch all around the world, in every city or town, given that each one will have been touched by the pandemic. “It could be something as simple as a doorknob or a balustrade—something mundane,” Rael said. “Something anyone would touch and recall this moment.”

But Rael couldn’t shake the idea of the copper penny. So personal and portable. He recalled a hundred-year-old wooden nickel his grandmother had kept, a token for a church anniversary. He had also recently started smelting down aluminum cans, and he found that friends were inexplicably drawn to the resulting ingots, many asking if they could take one home as a keepsake of nothing in particular. “What if all we need is a copper ball?” he wondered. A keepsake that anyone—that everyone—could have. One that might act as a proxy for the touches and smells that the virus prohibits, too. But how do you distribute a copper object to everyone on Earth? The logistics seem impossible. They also correspond exactly with the coordination needed to distribute a vaccine that would successfully inoculate the planet’s population. Perhaps the cure could come with the token that might preserve its own memory, like a talisman.

People have an attachment to the objects they make and use. They embed memories and carry them forward too. This one would conform to the shape of the human hand, both begging for touch and changing in response to it. “Every memorial would become completely unique and individualized over time,” San Fratello said. “Each memorial would be personal.” Such an expanded spirit of memorialization would include many more people than just the dead—the families, the friends, the caregivers, and the healthy, whose persistence will, hopefully, outlive the virus. Could the vessel that delivers the vaccine itself become the memorial? Rael wondered aloud to me. “It’s the one thing that would touch everybody but not touch anyone else.”

Sekou Cooke – Unmonument

“People will be affected by, and may still die of, COVID 20 or 30 years from now,” Sekou Cooke reminds me. That makes any memorial to the virus incomplete or temporary. We will never know exactly how many people SARS-CoV-2 infects or kills.

“So let’s change the question completely,” Cooke said. “Instead of designing a memorial to COVID-19, can we fundamentally question the nature of memorials themselves?” For one thing, humankind needs the pandemic to be temporary. For another, the Black Lives Matter protests that accompanied the pandemic over the summer also amplified an ongoing revelation about monuments and memorials in America: Many of them were deeply racist in the first place.

[Read: America’s first memorial to the victims of lynching]

Cooke, an architect and a professor at Syracuse University’s School of Architecture, has been grappling with architecture’s racist legacy his whole career. He advocates for a new method, hip-hop architecture, as an alternative. It’s all about setting aside expectations. “People want to know what a hip-hop building looks like,” Cooke told me. But that question misses the point: “Most of the time, hip-hop is about the process.” A lived experience of struggle informs art. When applied to architecture, hip-hop becomes a lens through which to inspire new design ideas, in which Black people can develop a different relationship to the built environment. “We can create something totally new,” he said.

When it comes to a COVID-19 monument, Cooke proposes an “unmonument” instead, one that samples from Black Lives Matter and other protest movements and spreads their DNA like a different kind of virus. “It first attacks our memorials to false leaders, then real ones, then attacks the monuments of capitalism and consumerism and industries too weak to resist,” Cooke wrote in a statement.

It would start at the Robert E. Lee Monument in Richmond, Virginia—a statue that graffiti and chalk have already redecorated. Rather than tear down the statue, Cooke wants to repurpose it. He would erect scaffolding around it, along with fencing and barricades, materials often used to stave off vandalism. Once installed, visitors would add elements atop: photographs, keepsakes, or other reminders of people affected by the pandemic—or by unchecked police violence, or by the neglect of declining economic outcomes.

From there, the memorial would expand to other locations, feeding off of other, even more hallowed sites of tribute, culture, and commerce. The Lincoln Memorial, perhaps, or even Times Square, although the design could take root anywhere; Cooke is more interested in facilitating its natural growth than prescribing sites in advance. He likens the process to erosion, wearing away the significance of these older structures. “Their histories are tainted,” Cooke said. As a result of his intervention, he hopes these monuments, and monuments in general, would cease to honor existing structures of power. True to the spirit of hip-hop, a statue, a memorial, a block, a whole district become materials to be remixed anew.

To some eyes, Cooke’s design might not even look like a design. That’s a good sign that the hip-hop architectural practice is working as intended. The designer’s agency doesn’t come from defining the form and function of a place from the top down, but by inviting the bottom-up reuse of monumental spaces: in the design of the circulation paths that funnel people through them in new ways; in defining how materials can adorn the site; in the organizing needed to inspire people to assemble there in the first place.

The Black Reconstruction Collective, a nonprofit in which Cooke is a member, has taken a similar approach to a forthcoming MoMA show on architecture and Blackness in America. Instead of curating a showcase for its 10 members, whom the museum curators invited, the group decided it was more important to give the platform away to other

Black architects and designers enacting projects on this theme, but without the collective’s power. It’s the opposite inclination that famous starchitects would adopt, given such a platform. “I’m actually all for blowing things up and starting things again,” Cooke said. “Architecture can completely reinvent itself from the ground up, but it has to do so by dismantling its most conservative institutions.” Including the inclination to build a memorial to the COVID-19 tragedy in the first place. Instead of a memorial to the pandemic, build a memorial to memorials instead. As we begin to forget the things we’ve long memorialized, Cooke writes, we begin to remember ourselves.