This article will introduce the uninitiated beginner to all the

immediate Git fundamentals needed to start work right away. This is a

crash course in Git for beginners.

Did you know? You can use your cloud server hosting as a private Git server.

Git Fundamentals and Options (Why Learn Git?)

Git is (arguably) the world’s most popular version control system. It

is actively developed and supported by a large community of users.

Git is…

- Decentralized, meaning work can be done independent of a centrally

located repository - Widely supported

- Hosted for free on popular websites like GitHub and BitBucket

- Universally supported across various operating systems

Command Line or GUI

When first learning how to use Git, you have a choice between using

the command line version and a graphical user interface (GUI) version.

In this article, we presume you are interesting in learning the

command line variant. There are certain benefits in using the command

line version of Git including:

- Wide support across various platforms

- Commands stay the same no matter where you are

- Allows for scripting and aliasing (to run favorite commands faster)

- Helps to solidify the conceptual framework behind Git

But if for any reason you choose to use a GUI, there are many popular

open source option including:

- Git Kraken

- Magit (for emacs)

- Git Extensions

- GitHub Desktop

- Sourcetree

The Working Directory

The working directory is the main directory for the project files. As

you’re learning more about Git you’ll often hear or read mention of

the working directory. It’s basically the directory (or, folder)

that contains the files for your project.

The working directory can be altered by Git. For example, you could

load previous versions of the project or integrate others’ code from

another branch of the project, and your working directory will change.

This means you must be careful not to accidentally overwrite files in

your working directory.

In order to start using your working directory, all you have to do is

create a directory and start adding your files to it.

In the next section, you will find out how to instruct the Git program

to start watching this directory for changes.

Initialize Repository

Before you begin your work you’ll need to “initialize” Git in your

working directory, with this command:

git init

This command initializes Git functionality in your working directory.

But what does that mean? Git initialization accomplishes the

following:

- Sets up a .git directory in your working directory

- This “hidden” directory keeps track of the files and special

reference markers needed by the Git program - As you get more advanced in Git, you can use some of the items in

this directory to achieve advanced effects, but not yet

- This “hidden” directory keeps track of the files and special

- Opens up your project for Git tracking

- Allows you to start running git commands

Upon initialization, your Git project is officially up and running.

Now you need to let Git know which files to start tracking.

The Staging Index

Like the working directory, the staging index is a fundamental concept

in Git that you must learn and commit to memory.

You can think of the staging index as a sort of list that tells Git

which files (or modifications to files) you want to commit to the

repository.

You use the staging index by invoking the git add command, for

example:

git add <name-of-file>

Or…

git add file1.php

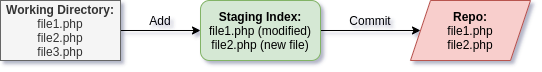

In the diagram below, suppose three files have been created in the

working directory. Notice:

- The first file has already been tracked by Git and was modified

- The second file is new to Git but was just added, indicating that

it’s a new file for Git to start tracking - The third file has not been added to the staging index, so Git is

not aware of it

This means that even if a file has been previously added to Git for

tracking, it must be added to the staging index again every time it is

modified, otherwise the changes will not be committed to the repository.

The Repository

Once you have added the files, and modifications to files, to the

staging index, it’s time to commit those changes to the repository.

The repository is the official, logged, and—sometimes—tagged

destination for your project files in one state.

You can think of the repository as the place where all the records of

the various states of your project are kept. Each note, or mark, is

termed a “commit,” because it is basically a commitment to the

permanent record of the project. This means if you’re working on

something like a software project, the program should be in a solid

working condition or at least a somewhat working state when a commit

is made.

Git requires that all commits be made with a log entry to briefly

notate the nature of the commit.

Some example commit messages might be:

- “Fixed bug on login screen”

- “Updated emphasis font”

- “Added phone number entry to form fields”

In order to start a commit, run this command:

git commit

This command, as is, will open your default text editor for writing in

your commit message.

To skip over the text editor, use the -m option and put your commit

message in quotes, like so:

git commit -m "Fixed bug on login screen"

And, accomplishing more with one command, you can add the -a option

to simultaneously add all file modifications to staging index before

committing:

git commit -am "Fixed bug on login screen"

The latter command demonstrates how the command line Git variant lets

you use various options to chain commands together, thus saving a

little time.

Branches

Finally, as you are now ready to embark on your journey in discovering

the magic of Git, you need to learn about how branches work.

Branches allow for unlimited iteration of your project files. For

example, if you want to test a new feature or bit of code, you can

create a separate “branch” of the project.

By default, every Git project has a master branch, or “upstream”

branch that is meant to reference the final/complete version of your

project.

By creating branches you can make unlimited changes to your project,

and commit them, without affecting the master copy.

When working with branches you can always switch back to the master

branch—or other branches to “checkout” the files or modifications in

that branch.

However, one caveat of branches is that you can only “checkout” other

branches from a clean state. Which means if you have uncommitted

changes in your current branch you cannot checkout other branches.

But if you’re unready to commit those changes on your current branch,

you can stash them aside for later.

In order to see what branch you’re currently on, you can run the git

branch command by itself:

git branch

If you haven’t created any alternative branches yet, you will see a

listing for the “master” branch, which you’re on by default.

To create a new branch you can run git branch followed by the name

of the branch you want to create, like so:

git branch <name-of-branch>

Now when you run git branch you’ll see “master” and the new branch

listed. Master will still be selected as your active branch.

In order to “checkout” a different branch, run the git checkout

command followed by the name of the branch you want to check out.

git checkout <name-of-branch>

You can check to make sure you’re on the new branch by running git

branch again to see that the new branch is selected/highlighted.

(It’s always good to check your work.)

Now, notice, if you make changes to the files on this branch, you will

not be able to switch back over to the “master” branch unless you

commit your changes or stash them.

To stash your changes, run git stash.

git stash

When you return to the new branch, you can unstash, or “pop,” your

changes. (Actually, you can pop changes on any branch. See the full

guide on git stash to learn more.)

Those are the very basics of Git. From there, you can master the

entire program because you have grounded yourself in the fundamentals.

If you have any issues, or unexpected errors, leave a comment below

and the InMotion community team will try to help out.