There’s a new app, and when isn’t there? This one is called E.gg, and it looks like a mix of Tumblr and GeoCities: The “About” page features a dancing-baby GIF, against a background of a starry night sky, with text in deliberately nauseating shades of highlighter yellow and green. It calls out the “raw and exploratory spirit” of the “Early Internet,” and reminisces about the days of “manically-blinking GIFs,” digital guest books, and wacky personal websites.

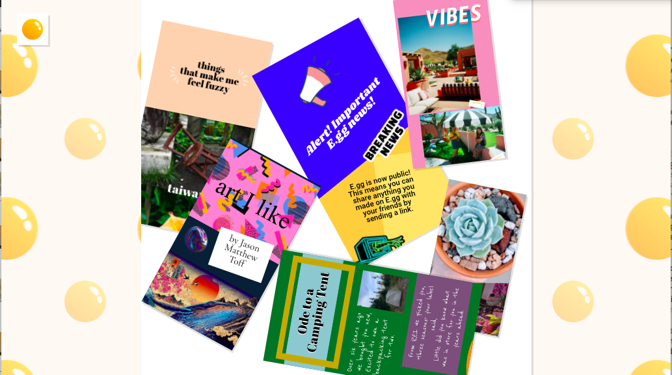

E.gg offers users the ability to create zine-y looking digital collages that it calls “canvases.” The team behind it poses a series of rhetorical questions by way of introduction: “What if people could express themselves more freely today? Can we make more room for the weird and off-beat? Give creative control back to people?” Unlike almost all current social-media platforms, it will not display “like” counts or allow comments.

There is little to indicate that this new oddity was created by Facebook, the company that killed off quirky, ultra-personalized personal websites and made everyone’s “profile” look nearly the same. And though the people who made it are obviously poking fun at their employers a bit, it is a Facebook product. Facebook’s in-house app incubator—the New Product Experimentation team—launched the limited beta test for E.gg on Tuesday, the day before CEO Mark Zuckerberg testified in front of members of Congress that his company has not engaged in anticompetitive practices to stifle its rivals. The product speaks plainly to Facebook’s apparent mindset for the past 16 years: The whole world should be connected, under Facebook’s umbrella, and competitors’ ideas exist to be appropriated for that purpose, whether as part of a core service or, now, as a nostalgic pet project.

Throughout yesterday’s hearing, members of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust painted a compelling picture of Facebook as a giant, gobbling up the social web before it was even clear what that web could have been.

[Read: The tech companies already won]

In that context, E.gg is fun to look at, but it also scans as a rhetorical exercise to prove a point. When I reached out to Facebook to hear more about why E.gg was created, I was directed to a recent report—commissioned by Facebook—showing that “about one-third of [the] top 100 most downloaded apps are new entrants each year.” In other words, that there is no monopoly on human attention, and there is plenty of room for creative upstarts. Ime Archibong, the head of the New Product Experimentation team, reiterated this point in an emailed statement, saying, “Last year, the average person had 93 apps installed on their phone and used 41 per month … All of this choice and competition fuels innovation.”

At the hearing, Representative Joe Neguse of Colorado hounded Zuckerberg over the consolidation of the social-media market, listing Myspace, Friendster, Orkut, and Cyworld as examples of Facebook competitors that existed in 2004—when the company launched—but either don’t exist or don’t matter now. Zuckerberg disagreed with the implication, responding, “Congressman, those were some of the competitors, and it’s only gotten more competitive since.”

Some of Facebook’s toughest questioning yesterday came from Representative Jerry Nadler of New York, who pressed Zuckerberg on the company’s 2012 acquisition of Instagram. He quoted from emails obtained by the subcommittee in which Zuckerberg appears to identify Instagram as a competitive threat, and to consider this threat as a primary reason for acquiring the platform—on its face, an obvious violation of antitrust law. Nadler was the only member of the committee to openly suggest that Instagram should be spun off from Facebook as a separate company.

In his defense, Zuckerberg argued that “almost no one” thought of Instagram as a “general social network” in 2012. It was just a photo-sharing app, but Facebook made it into a juggernaut. A logical follow-up question went unsaid: Might Instagram have become something more interesting than a Facebook property with more than 1 billion users and all of the same large-scale moderation problems as its parent company? Nor was there much discussion of the many methods by which Facebook has mutated Instagram to function more like Facebook itself, alienated its co-founders, and knit the apps together in obnoxious ways.

[Read: The tech giants are dangerous, and Congress knows it]

Facebook is so big that the subcommittee didn’t have time to address all the ways it has worked to copy or consume competitors. The $16 billion acquisition of the messaging giant WhatsApp in 2014 barely came up. Representative Val Demings of Florida quoted from emails in which Facebook employees discussed cutting off Pinterest’s access to certain Facebook services, but one decision that wasn’t mentioned during the hearing was the similar 2013 move—approved by Zuckerberg personally—to cut off Vine’s access to users’ Facebook friends lists. The beloved short-form video app struggled to grow, and was shut down in early 2017. The hearing also barely touched on Facebook’s attempt to buy Snapchat, or its subsequent mimicry of the app’s core features. And no lawmaker asked about Facebook’s new video-editing app, Reels, which Facebook is reportedly paying TikTok stars to switch over to.

Still, the basic premise of the representatives’ interrogation at the hearing was clear: We have no idea what the social web could have looked like if one superpower hadn’t made it all look the same. After 16 years of thumbs-ups and follower counts and sponsored posts, it’s almost impossible to imagine.

E.gg’s “About” page lists a handful of guiding principles, including “creativity as its own solitary reward.” It’s a winking pivot from the engagement incentives that its parent company codified, a freedom bought by the enormous wealth those systems have amassed.