Have you ever wondered how attackers map out a target’s network infrastructure before launching an attack? Or, how security professionals identify misconfigurations that could lead to data breaches? The answer often lies in DNS reconnaissance, the art of extracting valuable information from Domain Name System records.

DNS contains far more information than most people realize. Beyond simply translating domain names to IP addresses, DNS records can reveal mail servers, subdomains, network ranges, and even security configurations.

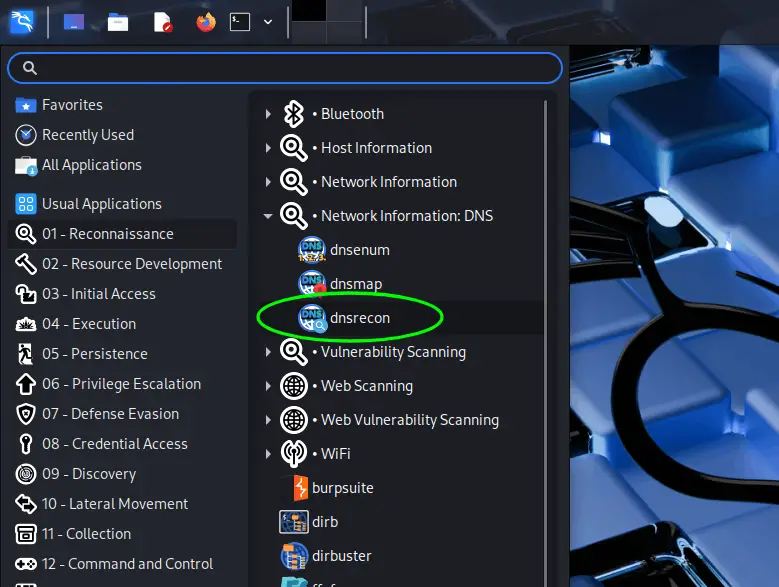

In this pentesting lab, we’ll explore dnsrecon, a powerful Python-based tool that should be in every security professional’s toolkit. Whether you’re conducting a penetration test, troubleshooting network issues, or simply learning about DNS security, this tool provides the capabilities you need for thorough DNS enumeration.

What is dnsrecon?

DNSRecon is an advanced DNS enumeration tool originally created by Carlos Perez. What began as a Ruby learning project in 2007 has evolved into a feature-rich Python script that security professionals worldwide rely on for comprehensive DNS assessment .

Unlike basic DNS lookup tools, dnsrecon provides a wide range of capabilities in a single utility:

- General DNS record enumeration (SOA, NS, A, AAAA, MX, TXT, SPF, SRV)

- Zone transfer attempts to discover hidden subdomains

- Brute-force subdomain discovery using wordlists

- Reverse DNS lookups for IP range analysis

- DNSSEC zone walking to enumerate all records in a DNSSEC-signed zone

- DNS cache snooping to see what records are cached on specific servers

This tool comes pre-installed in Kali Linux, making it readily available for penetration testers and security researchers .

Installing dnsrecon

If you’re using Kali Linux, dnsrecon comes pre-installed:

For other Linux distributions, the installation process is straightforward:

# Clone the repository from GitHub

git clone https://github.com/darkoperator/dnsrecon

# Navigate to the directory

cd dnsrecon

# Install required dependencies

pip3 install -r requirements.txt --no-warn-script-location

The tool requires Python 3 and several libraries including dnspython, lxml, and netaddr.

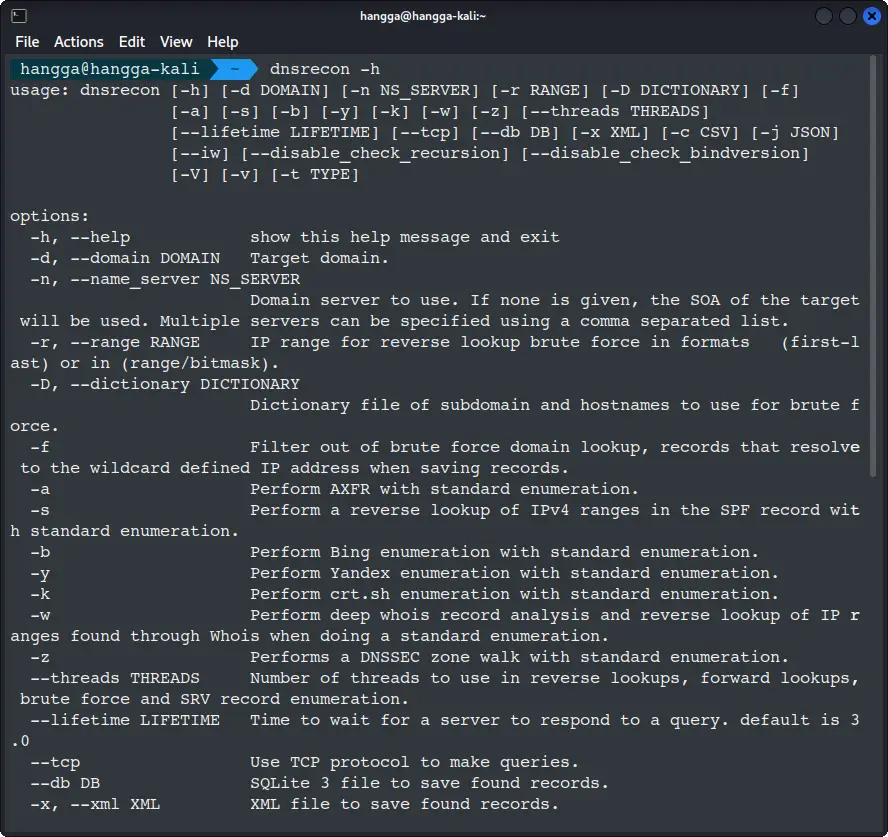

Basic command structure of dnsrecon

Before diving into complex scenarios, let’s examine the basic command structure:

dnsrecon -d <domain> [options]

The -d flag specifies your target domain, which is the only required parameter for basic scans. To see all available options, use the help flag:

dnsrecon -h

Standard DNS Record Enumeration

Let’s start with a fundamental scan against a test domain. We’ll use vulnweb.com throughout our examples, a deliberately vulnerable website perfect for practice.

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com

What do these findings allow you to do? What do they hide? And how do they change the way you approach the target? Let’s see.

Wildcard DNS: The recon noise machine

Wildcard DNS is the first thing that jumps out:

[!] Wildcard resolution is enabled on this domain

[!] It is resolving to 44.228.249.3

[!] All queries will resolve to this list of addresses!!

From a pentesting perspective, wildcard DNS is not just a configuration detail. It directly affects recon quality.

Why this matters during recon:

- When you brute force subdomains, everything resolves successfully. That means your wordlist results become useless unless you filter for HTTP response patterns, content length, favicon hashing, CNAME behavior, or similar.

- Wildcard DNS increases false positives for automated tools such as

dnsrecon,amass, andsubfinder. - Some pentesters mistakenly think they found “hundreds of live subdomains” when actually the domain is feeding the same IP for anything you throw at it.

In short, wildcard DNS forces you to rely on content-based discovery instead of DNS-only enumeration.

Missing DNSSEC: Not directly exploitable, but still notable

[-] DNSSEC is not configured for vulnweb.com

As a pentester, DNSSEC absence is rarely something you exploit directly.

Instead, it’s more like a missing seatbelt: bad for defenders, but not necessarily an immediate attack path for you. Still, it matters because:

- It leaves room for DNS spoofing in certain test scenarios.

- It makes traffic redirection attacks more feasible in misconfigured networks.

- It shows the domain is not following modern DNS hygiene, which sometimes correlates with other weaknesses.

But for practical exploitation, DNSSEC absence is usually a yellow flag, not a direct entry point.

Open recursion on authoritative servers: The real red flag

This is the finding that actually stands out:

[-] Recursion enabled on NS Server 199.167.66.108

[-] Recursion enabled on NS Server 199.167.66.107

[-] Recursion enabled on NS Server 104.37.178.107

[-] Recursion enabled on NS Server 104.37.178.108

Authoritative servers should not be resolving queries for arbitrary domains. Yet here they are, happily performing recursive lookups.

What this means to you as a pentester:

- These servers can be abused as amplifiers in a DNS-based DDoS attack.

- They may leak resolving behavior or cached data that helps you piece together external infrastructure.

- They let you see how the server handles more complex DNS queries, which sometimes reveals misconfigurations you can pivot on.

Even though you might not use this to break into vulnweb.com directly, it is still a high-value finding, especially in a real engagement.

Software version disclosure: Free threat intelligence

[*] Bind Version for 199.167.66.107 "9.18.30-0ubuntu0.24.04.2-Ubuntu"

With this, you can look up vulnerabilities for that specific release, filter for CVEs matching BIND 9.18.x issues such as cache poisoning vectors or DoS flaws and understand the OS base behind the scenes, which might help fingerprint the broader stack

As a pentester, version banners are not always exploitable, but they are often useful.

TXT Records: Email cecurity that’s… there, but bot there

SPF with -all

[*] TXT vulnweb.com v=spf1 -all

This means the domain sends no legitimate email at all. If you are attacking a real production target, this stops you from using spoofed emails as an initial attack vector. This is expected for a demo target.

Misconfigured DMARC and DKIM

[*] TXT _dmarc.vulnweb.com v=spf1 -all

[*] TXT _domainkey.vulnweb.com v=spf1 -all

These are incorrect. DMARC and DKIM should not contain SPF syntax. This is evidence of misconfiguration discipline. Misconfigured DNS often means misconfigured web servers or internal systems. It could enable email phishing if the domain were actually used in the real world.

For vulnweb.com specifically, this is more of a teaching example than an attack path.

A Record: The main target

[*] A vulnweb.com 44.228.249.3

Nothing surprising here. This is the host where your HTTP-based testing will happen. But combined with wildcard DNS, it means every fake subdomain also points here, so you must use application-layer behavior to confirm real hosts.

Final Pentester-Oriented Summary

Here’s the quick mental checklist a pentester would build from these results:

High-signal findings:

- Wildcard DNS: Must switch to HTTP-based subdomain validation.

- Open recursion on all authoritative name servers: Highly unusual and could be abused for amplification or further DNS trickery.

Medium-signal findings:

- Version disclosure for BIND: Useful for attack planning.

- Misconfigured DMARC / DKIM: Signs of sloppy DNS management.

Low-signal findings:

- Missing DNSSEC: Rarely actionable during a pentest.

- SPF -all: Prevents spoofing, but nothing to exploit.

Targeted record enumeration

For more focused reconnaissance, you can specify particular record types using the -t flag:

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -t std

This command explicitly requests a standard record enumeration, useful when you want to avoid the overhead of more intensive scans. dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -t std and dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com produce the same output because std is dnsrecon’s default mode; omitting -t runs std automatically.

Attempting zone transfers

A zone transfer (AXFR) is essentially a database replication between DNS servers. When misconfigured, it can reveal the entire DNS zone file, including all subdomains and associated records, a goldmine for attackers.

To test all authoritative name servers for zone transfer vulnerabilities:

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -t axfr

Here is the output:

Checking for Zone Transfer for vulnweb.com name servers

[*] Resolving SOA Record

[+] SOA ns1.eurodns.com 199.167.66.107

[+] SOA ns1.eurodns.com 2610:1c8:b002::107

[*] Resolving NS Records

[*] NS Servers found:

[+] NS ns3.eurodns.com 199.167.66.108

[+] NS ns3.eurodns.com 2610:1c8:b002::108

[+] NS ns1.eurodns.com 199.167.66.107

[+] NS ns1.eurodns.com 2610:1c8:b002::107

[+] NS ns2.eurodns.com 104.37.178.107

[+] NS ns2.eurodns.com 2610:1c8:b001::107

[+] NS ns4.eurodns.com 104.37.178.108

[+] NS ns4.eurodns.com 2610:1c8:b001::108

[*] Removing any duplicate NS server IP Addresses...

[*]

[*] Trying NS server 2610:1c8:b001::108

[-] Zone Transfer Failed for 2610:1c8:b001::108!

[-] Port 53 TCP is being filtered

[*]

[*] Trying NS server 2610:1c8:b002::107

[-] Zone Transfer Failed for 2610:1c8:b002::107!

[-] Port 53 TCP is being filtered

[*]

[*] Trying NS server 2610:1c8:b002::108

[-] Zone Transfer Failed for 2610:1c8:b002::108!

[-] Port 53 TCP is being filtered

[*]

[*] Trying NS server 104.37.178.107

[+] 104.37.178.107 Has port 53 TCP Open

[-] Zone Transfer Failed (Zone transfer error: NOTAUTH)

[*]

[*] Trying NS server 199.167.66.107

[+] 199.167.66.107 Has port 53 TCP Open

[-] Zone Transfer Failed (Zone transfer error: NOTAUTH)

[*]

[*] Trying NS server 2610:1c8:b001::107

[-] Zone Transfer Failed for 2610:1c8:b001::107!

[-] Port 53 TCP is being filtered

[*]

[*] Trying NS server 199.167.66.108

[+] 199.167.66.108 Has port 53 TCP Open

[-] Zone Transfer Failed (Zone transfer error: NOTAUTH)

[*]

[*] Trying NS server 104.37.178.108

[+] 104.37.178.108 Has port 53 TCP Open

[-] Zone Transfer Failed (Zone transfer error: NOTAUTH)

If successful, this command will dump the complete zone database, potentially exposing internal hosts, development servers, and other infrastructure not meant for public disclosure. While most modern DNS servers properly restrict zone transfers, you’d be surprised how many organizations still have misconfigured servers.

Brute-forcing subdomains

One of dnsrecon’s most powerful features is its ability to brute-force subdomains using wordlists. This technique discovers hidden subdomains that wouldn’t appear in normal DNS queries.

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -t brt

0:00/0:11Video progressAdjust volume

What happened here: The tool performed a brute force attack to discover subdomains using a built-in wordlist (/usr/share/dnsrecon/dnsrecon/data/namelist.txt. It found 1,910 subdomains pointing to mostly the same IP address

Key Findings:

- Wildcard DNS enabled – All non-existent subdomains resolve to

44.228.249.3 - Massive subdomain enumeration – Hundreds of common subdomain names discovered

- Two distinct IPs found:

44.228.249.3(most subdomains)44.238.29.244(testasp.vulnweb.com, testaspnet.vulnweb.com)127.0.0.1(localhost.vulnweb.com)

This type of scan helps penetration testers discover hidden subdomains and thus potential attack surfaces, misconfigured DNS settings, development/test environments

The results show this domain has very permissive DNS settings, making it easy to enumerate potential targets for further security testing.

⚠️ Many domains use wildcard DNS records that can interfere with brute-force enumeration. When wildcard records are detected, dnsrecon will alert you. Use the -f flag to filter these out:

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -t brt -D wordlist.txt -f

Alternatively, use --iw to continue brute-forcing even when wildcards are detected.

Reverse DNS Lookups

Reverse DNS lookups can help you map the network landscape around a target domain. By querying PTR records for an IP range, you can discover additional domains and hosts belonging to the same organization.

dnsrecon -r 199.167.66.108/24

[*] Performing Reverse Lookup from 199.167.66.0 to 199.167.66.255

[+] PTR ns3.nudns.com 199.167.66.2

[+] PTR ns1.nudns.com 199.167.66.1

[+] PTR ns1.elv8.net 199.167.66.5

[+] PTR ns7.dns.com 199.167.66.4

[+] PTR ns5.dns.com 199.167.66.3

[+] PTR ns3.elv8.net 199.167.66.6

[+] PTR dns5.registrar-servers.com 199.167.66.12

[+] PTR dns1.registrar-servers.com 199.167.66.10

[+] PTR ns5.101domain.com 199.167.66.16

[+] PTR dns3.registrar-servers.com 199.167.66.11

[+] PTR ns7.101domain.com 199.167.66.17

[+] PTR dns3.brandshelter.info 199.167.66.25

[+] PTR ans4.brandshelter.net 199.167.66.27

[+] PTR dns1.brandshelter.com 199.167.66.24

[+] PTR ans2.brandshelter.de 199.167.66.26

[+] PTR ns3.leftofthedot.com 199.167.66.31

[+] PTR ns1.dgtldns.com 199.167.66.35

[+] PTR ns3.dgtldns.com 199.167.66.36

[+] PTR ns3.dsgnr-dns.com 199.167.66.38

[+] PTR ns1.dsgnr-dns.com 199.167.66.37

[+] PTR n.ameservers.eu 199.167.66.41

[+] PTR ns1.designer24.ch 199.167.66.45

[+] PTR ns1.leftofthedot.com 199.167.66.30

[+] PTR ns5.designer24.ch 199.167.66.47

[+] PTR ns3.designer24.ch 199.167.66.46

[+] PTR ns3.vargonen.net 199.167.66.51

[+] PTR ns1.vargonen.net 199.167.66.50

[+] PTR n.ameserver.be 199.167.66.40

[+] PTR ns3.tera.lt 199.167.66.56

[+] PTR ns1.istreamlive.com 199.167.66.57

[+] PTR ns2.monroehosting.com 199.167.66.60

[+] PTR ns3.istreamlive.com 199.167.66.58

[+] PTR ns3.4thenet.net 199.167.66.62

[+] PTR ns1.wixidns.com 199.167.66.59

[+] PTR ns1.klarys.com 199.167.66.63

[+] PTR ns3.londondrugs.com 199.167.66.66

[+] PTR ns1.4thenet.net 199.167.66.61

[+] PTR ns1.dns-anycast.net 199.167.66.67

[+] PTR ns3.dns-anycast.net 199.167.66.68

[+] PTR ns3.dns.com.sv 199.167.66.70

[+] PTR ns1.dns.com.sv 199.167.66.69

[+] PTR ns3.perfectaddress.com 199.167.66.74

[+] PTR ns3.smestorage.com 199.167.66.76

[+] PTR ns1.perfectaddress.com 199.167.66.73

[+] PTR ns3.crain.com 199.167.66.80

[+] PTR ns1.softigation.net 199.167.66.77

[+] PTR ns1.dnsstation.com 199.167.66.81

[+] PTR 0.0.0.0-254.com 199.167.66.82

[+] PTR ns1.smestorage.com 199.167.66.75

[+] PTR ns3.domain.jobs 199.167.66.84

[+] PTR ns3.softigation.net 199.167.66.78

[+] PTR ns3.retailup.com 199.167.66.86

[+] PTR ns3.icfwebservices.com 199.167.66.88

[+] PTR ns1.retailup.com 199.167.66.85

[+] PTR ns1.crain.com 199.167.66.79

[+] PTR ns3.lightningbase.com 199.167.66.90

[+] PTR ns1.lightningbase.com 199.167.66.89

[+] PTR ns1.flamingdns.co.uk 199.167.66.91

[+] PTR ns.bostongreengoods.com 199.167.66.93

[+] PTR ns1.domain.jobs 199.167.66.83

[+] PTR ns1.icfwebservices.com 199.167.66.87

[+] PTR ns3.bostongreengoods.com 199.167.66.94

[+] PTR ns3.edcogroup.net 199.167.66.96

[+] PTR ns1.edcogroup.net 199.167.66.95

[+] PTR ns1.myserver.co 199.167.66.97

[+] PTR ns3.flamingdns.co.uk 199.167.66.92

[+] PTR ns1.subhostingdns.com 199.167.66.99

[+] PTR ns3.subhostingdns.com 199.167.66.100

[+] PTR ns3.myserver.co 199.167.66.98

[+] PTR premium-ns1.dnsowl.com 199.167.66.105

[+] PTR ns1.eurodns.com 199.167.66.107

[+] PTR ns3.ebrandservices.com 199.167.66.110

[+] PTR ns3.eurodns.com 199.167.66.108

[+] PTR ns1.moreweb.nz 199.167.66.111

[+] PTR ns-a.eurodns.com 199.167.66.106

[+] PTR ns1.prodns.net 199.167.66.113

[+] PTR ns3.ebrand.be 199.167.66.116

[+] PTR ns3.moreweb.nz 199.167.66.112

[+] PTR ns1.ebrandservices.com 199.167.66.109

[+] PTR ns3.prodns.net 199.167.66.114

[+] PTR ns1.ebrand.be 199.167.66.115

[+] PTR ns3.entorno.com 199.167.66.120

[+] PTR ns3.fluccs.domains 199.167.66.118

[+] PTR ns1.entorno.com 199.167.66.119

[+] PTR ns1.fluccs.domains 199.167.66.117

[+] PTR ns1-a.entorno.com 199.167.66.121

[+] PTR premium-ns3.dnsowl.com 199.167.66.150

[+] PTR ns-c.eurodns.eu 199.167.66.151

[+] PTR fail.fixallproblems.com 199.167.66.252

[+] PTR mx3.anti-error.com 199.167.66.253

[+] PTR mx1.anti-error.com 199.167.66.254

[+] 91 Records Found

That last command didn’t just look at one website; it performed a reverse lookup on an entire block of 256 IP addresses belonging to a DNS hosting provider.

Think of it like this: instead of looking up a name to find an address (a forward lookup), we took a whole neighborhood of IP addresses and asked, “What names live here?”

The result is a fascinating glimpse into the backbone of the internet. We found 91 different domain nameservers all hosted within that same network block. These aren’t websites you visit, but the behind-the-scenes servers that tell the internet where to find those websites.

You can see nameservers for various domain registrars and hosting companies, like:

eurodns.comdnsowl.comregistrar-servers.comwixidns.com

This scan reveals a common practice where many providers host their critical DNS infrastructure in the same reliable data centers. It’s a reminder of how interconnected and shared the underlying infrastructure of the web truly is.

For a more targeted approach that automatically uses IP ranges found in SPF records:

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -s

The -s flag makes dnsrecon expand and perform reverse lookups on any IP ranges it finds inside DNS or TXT records (especially SPF entries). The normal command does not do that.

In the -s version, dnsrecon prints this additional process:

[*] Expanding IP ranges found in DNS and TXT records for Reverse Look-up

[*] No IP Ranges were found in SPF and TXT Records

That part never appears in the plain scan. So, the -s version is basically saying, “I checked the TXT and SPF records for IP ranges, but none were found.”

Even though -s enables additional lookup behavior, there were no SPF entries that listed IP networks (for example, ip4:198.51.100.0/24). Because of that, both scans returned identical DNS information.

DNSSEC zone walking

For domains protected by DNSSEC (DNS Security Extensions), you can sometimes perform a zone walking attack to enumerate all records in the zone:

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -t zonewalk

This technique exploits the NSEC records in DNSSEC to walk through the entire zone, revealing all records in sequence. While this vulnerability has been addressed in newer implementations with NSEC3, many domains still use the vulnerable NSEC approach.

💡Combining enumeration techniques

For comprehensive assessment, chain multiple enumeration types:

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -a -s -b -k -w -z --threads 10

This single command combines standard enumeration with zone transfer attempts (-a), reverse lookup of SPF record ranges (-s), bing search enumeration (-b), crt.sh certificate enumeration (-k), deep whois analysis (-w) and DNSSEC zone walking (-z)

Saving the results for future analysis

Professional reconnaissance involves documenting your findings. Dnsrecon supports multiple output formats perfect for reporting and further analysis:

# XML format

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -x results.xml

# JSON format

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -j results.json

# SQLite database

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com --db results.sqlite

# CSV format

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -c results.csv

Each format has its advantages: JSON and XML preserve the complete structure of the data, CSV is easily imported into spreadsheets, and SQLite enables complex queries against your results.

Let’s try saving to csv:

Let’s take a look at the file:

Comprehensive scanning with saved results

In real-world scenarios, you’ll often combine multiple techniques and save the output:

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -t std -t axfr -t brt -D /usr/share/wordlists/dnsmap.txt -x comprehensive_scan.xml

This command performs standard enumeration, zone transfer attempts, and brute-force subdomain discovery, then saves all findings to an XML file for later analysis.

💡 Save time with optimized performance

DNS enumeration can be time-consuming, especially with large wordlists. Dnsrecon offers several options to optimize performance:

dnsrecon -d vulnweb.com -t brt -D large_wordlist.txt --threads 20 --lifetime 5

--threads: Increases the number of concurrent queries (default is lower)--lifetime: Sets how long to wait for server responses (default is 3 seconds)--tcp: Uses TCP instead of UDP for more reliable queries

Be careful with thread counts as setting them too high may overwhelm target servers or trigger rate limiting.

How can you integrate dnsrecon into security assessments?

While we’ve focused on individual commands, dnsrecon truly shines when integrated into broader security workflows:

- Initial reconnaissance: Start with basic enumeration to map the visible infrastructure

- Subdomain discovery: Use brute-forcing and search engine enumeration to find hidden assets

- Vulnerability identification: Look for misconfigurations like open zone transfers

- Network mapping: Combine forward and reverse lookups to understand network topology

- Reporting: Use structured outputs to document findings for clients or management

Many organizations monitor DNS query patterns, and aggressive scanning may trigger security alerts. Adjust your timing and thread counts to be respectful of target infrastructure.

The key to mastery is understanding which techniques apply to your specific scenario and how to combine them efficiently. Start with basic enumeration to understand the domain’s structure, then progress to more advanced methods based on your initial findings.

As you continue your DNS reconnaissance journey, remember that tools are only part of the equation. Developing your analytical skills to interpret results and identify significant patterns will ultimately make you more effective in both offensive and defensive security roles.