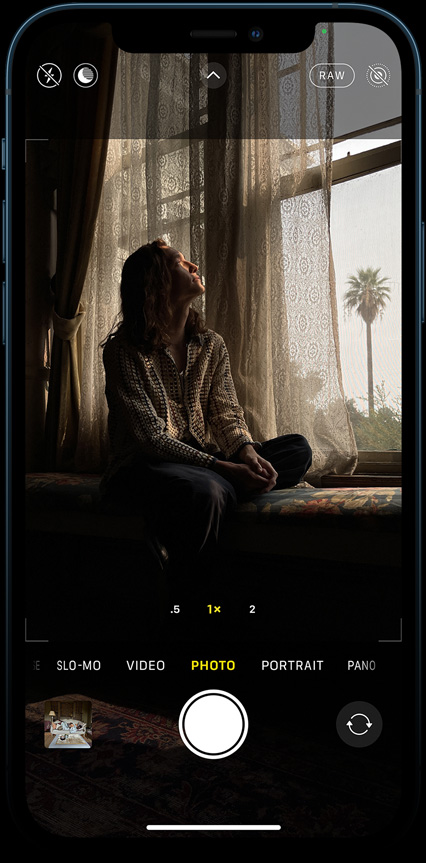

Apple’s iPhone 12 Pro heaps improvements on the already formidable power of its camera system, adding features that will be prized by “serious” photographers — that is to say, the type who like to really mess around with their shots after the fact. Of course, the upgrades will also be noticeable for us “fire and forget” shooters as well.

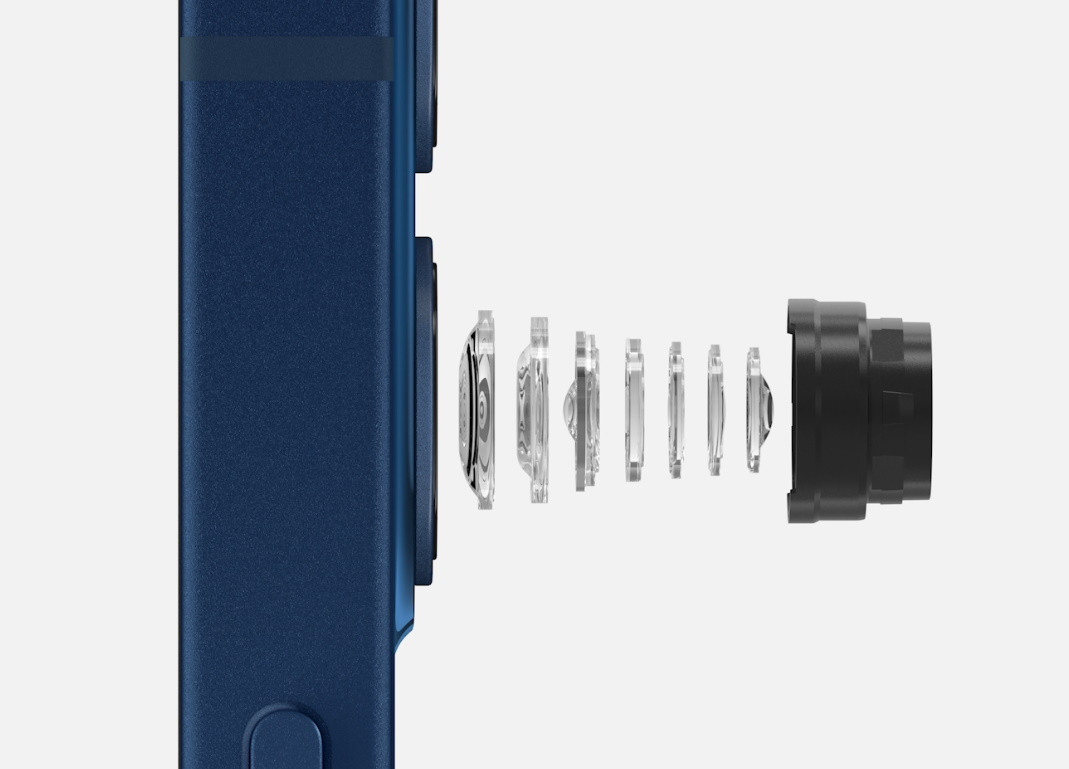

The most tangible change is the redesign of two of the three lens systems on the rear camera assembly. The Pro Max comes with a new, deeper telephoto camera: a 65 mm-equivalent rather than the 52 mm found on previous phones. This closer optical zoom will be prized by many; after all, 52 mm is still quite wide for portrait shots.

The improved wide-angle lens, common to all the new iPhone 12 models, has had its lens assembly simplified down to seven elements, improving light transmission and getting its equivalent aperture to F/1.6. At this scale, practically every photon counts, especially for the revamped Night Mode.

Image Credits: Apple

Perhaps a more consequential (and portentous) hardware change is the introduction of sensor-level image stabilization to the wide camera. This system, first used in DSLRs, detects motion and shifts the sensor a tiny bit to compensate for it, thousands of times per second. It’s a simpler, lighter-weight alternative to solutions that shift the lens itself.

Practically every flagship phone out there has some form of image stabilization, but implementations matter, so hands-on testing will determine whether this one is, in Apple’s words, “a game changer.” At any rate, it suggests that this is going to be a feature of the iPhone camera system going forward, and gains we see from it are here to stay; the presenter at today’s virtual event suggested a full F-stop, allowing two-second handheld exposures, but I’d take that with a grain of salt.

Image Credits: Apple

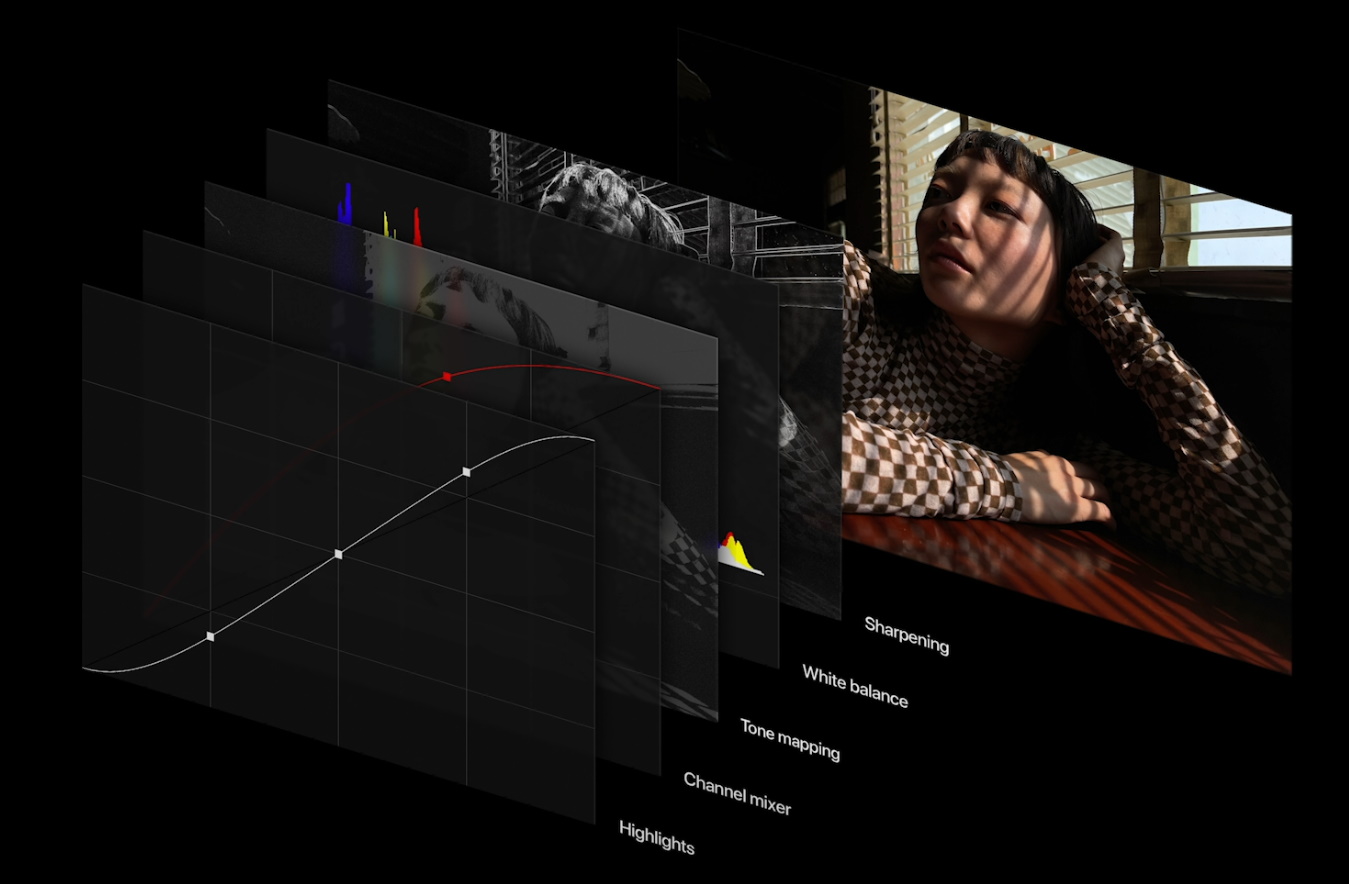

On the software side, the introduction of Apple ProRAW will be a godsend to photographers who use the iPhone either as a primary or secondary camera. When you take a photo, only a fraction of the information the sensor collects ends up on your screen — a huge amount of processing goes into removing redundant data, punching up colors, finding a good tone curve and so on. This produces a good-looking image at the cost of customizability; once you throw away that “extra” information, the colors and tone are restricted to a much narrower range of adjustment.

Image Credits: Apple

RAW files are the answer to this, as DSLR photographers know — they’re a minimally processed representation of what the sensor collects, letting the user do all the work to make the photo look good. Being able to shoot to a RAW format (or RAW-adjacent; we’ll know more with hands-on testing) frees up photographers who may have felt hemmed in by the iPhone’s default image processing. There were ways of getting around this before, but Apple has an advantage over third-party apps with its low-level access to the camera architecture, so this format will probably be the new standard.

This newfound elasticity at the image format level also enables the iPhone Pros to shoot in Dolby Vision, a grading standard usually applied in editing suites after you shoot your movie or commercial on a digital cinema camera. Shooting directly to it may be helpful to people planning to use the format but shooting with iPhones as B cameras. If cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki approves, it’s good enough for pretty much everyone else on Earth. I sincerely doubt anyone will cut their work together on the phone, though.

These two advances, ProRAW and Dolby, suggest that Apple’s improved silicon has left a lot of wiggle room in the photography backend. As I’ve written before, this is the most important segment of the imaging workflow right now, and the company is probably coming up with all kinds of ways to take advantage of the power offered by the latest chips.

Though larger cameras and lenses still offer advantages that the iPhone can never hope to match, the reverse is true as well. And the closer the iPhone gets to offering cinema-like quality — even if it’s simulated — the greater its advantages of portability and ease of use grow in proportion. Apple has been ruthlessly targeting enthusiast photographers, who aren’t quite sure if they want to buy a DSLR or mirrorless system in addition to a phone with a nice camera. By sweetening the deal on the phone side, Apple surely rakes in more of these users every generation.

Of course the Pro phones come at a significant premium over the normal range of iPhone devices (the Max starts at $1,099), but these improvements aren’t impossible or really even difficult to bring to lower-end models — most of them will probably trickle down next year. Of course, by then a whole new set of features will have been cooked up for the Pro devices. For photographers, however, planned obsolescence is part of the lifestyle.

![]()