In today’s rapidly evolving technology landscape, it’s common for applications to migrate to the cloud to embrace the microservice architecture. While this architectural approach offers scalability, reusability, and adaptability, it also presents a unique challenge: effectively managing communication between these microservices. Successfully coordinating messages among these services is a fundamental aspect of their design. There are two popular methodologies available to tackle this challenge. The first, Service Orchestration, was discussed in my previous article. In this article, we will dig into the second methodology: Choreography. We aim to comprehensively understand the nuances, advantages, and disadvantages that the Choreography methodology brings.

Problem Context

To address the communication challenge, we introduced the concept of an orchestrator, a central authority tasked with coordinating and streamlining the flow of transactions across these autonomous microservices. But here’s the question that looms large: Is the Orchestration Pattern a universal solution, or does its effectiveness vary depending on the scenario? Can a central orchestrator virtually manage all the business problems, or are there scenarios where a different approach besides being preferable is also essential?

The problem statement is the same as we have already covered during the discussion of the Orchestration Pattern. We have a collection of microservices, where each microservice is responsible for a specific operation or a particular domain. Yet, they operate independently, almost like parallel universes, often unaware of each other’s existence. Imagine a user initiating a request like submitting forms or searching a catalogue. These actions set off a series of business transactions that ripple across this microservices cluster. The challenge is clear: How can we ensure these transactions flow from one microservice to another, completing a successful business transaction? To answer this, we need to evaluate the costs associated and explore the intricacies of adopting the Orchestration Pattern.

Avoiding Distributed Monolith Anti-pattern

While designing for effective microservices architecture, it is crucial to stay clear of the “Distributed Monolith” anti-pattern. This term is often associated with scenarios where the Orchestration Pattern while providing some benefits, can introduce complexities and challenges that might not make it the desired solution. Let us have a look.

1. Tightly Coupled Services

In the Orchestration Pattern, all services are linked inseparably to the orchestrator. Each service must explicitly receive commands and report back to the orchestrator. This interdependence mandates that the orchestrator possess some domain knowledge about the responsibilities of each service.<br>

Now, envision introducing a new component to this business flow to address one of the new requirements. The new module will mandate a change in the existing flow and rewiring of the orchestrator. Precise coordination is necessary, potentially affecting a currently deployed logic. While a well-structured orchestrator can facilitate this process, such implementations often become complicated to manage over time.

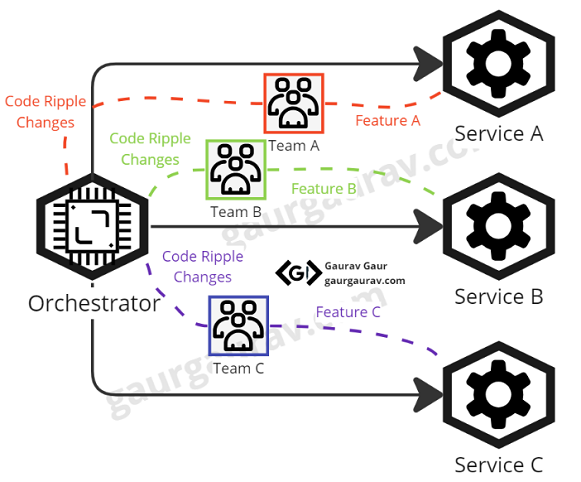

2. Tightly Coupled Teams

One of the primary reasons for adopting a microservices architecture is to expedite development by releasing teams from interdependencies. However, when employing the Orchestration Pattern, an interesting dynamic emerges. Consider a scenario where Team A is busy enhancing a feature while Team B is making updates to their service. Simultaneously, Team C is adding new functionality to the solution.

Since the orchestrator service tightly couples with all these teams’ services, all three teams must collaborate to ensure that their respective changes to the orchestrator service integrate seamlessly with existing and upcoming flows. This coordination often feels like working with monolithic applications, where the teams are bound by release cycles for significant changes.

By proactively recognizing these challenges within the Orchestration Pattern, we can equip ourselves to make informed architectural decisions, ensuring that our microservices ecosystem remains agile, scalable, and efficient. With this anti-pattern, we will encounter all the problems of the monolithic architecture and all the issues of the microservices architecture. Now, the question arises: Is there a pattern that can guide us in designing a solution capable of addressing these complex scenarios?

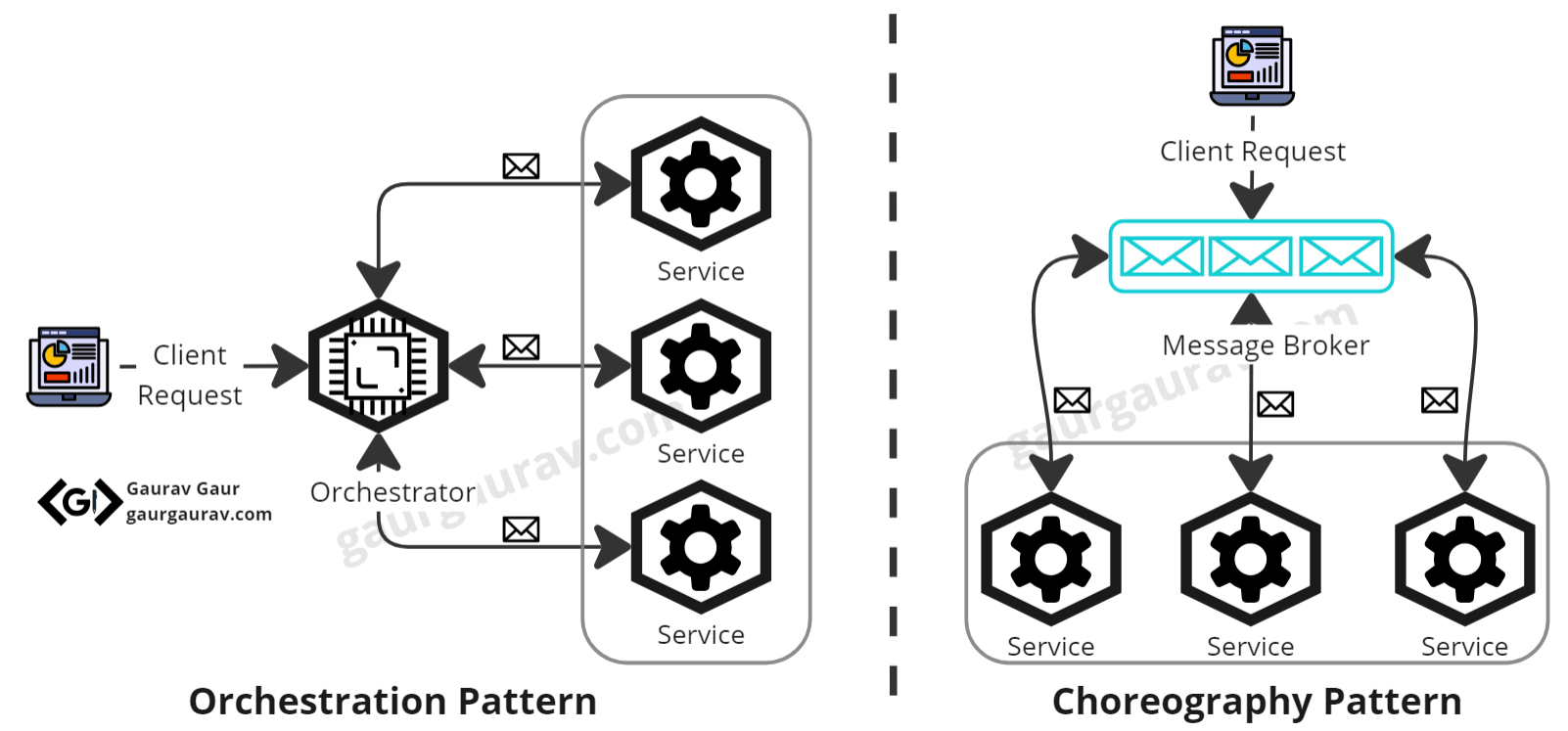

Exploring the Choreography Pattern

In contrast to the Orchestration Pattern’s centralized conductor, the Choreography Pattern utilizes a dumb message broker. This shift promotes loose coupling among microservices, untangling the web of interdependencies. Now, every microservice becomes an autonomous contributor, deciding when and how to execute its steps.

Imagine the Choreography Pattern as a graceful dance choreography. In a dance, performers receive instructions on how to execute their steps, yet each dancer retains individual responsibility for their performance. Similarly, this pattern directs seamless business processes for microservices, where each service takes its cue, much like a dancer following their choreographer.

This chain of events continues, each microservice taking its turn until the entire transaction is completed. Think of it as an elaborate dance performance where every step leads to the next. To dive deeper into the Choreography Pattern, let’s walk through a practical example that will illuminate its workings and benefits.

Use Case

Now that we’ve established some understanding of the Choreography Pattern, let’s take a practical scenario to grasp its real-world application. The example revolves around a dynamic job feed solution offered by a recruitment agency. This service streamlines the job-seeking process, offering applicants tailored job opportunities based on their preferences while ensuring a seamless user experience.

The recruitment agency invites applicants to share their profiles, job preferences and resumes via an interactive form hosted on their job feed service. This data serves the agency to continuously search the job market for openings that align with each applicant’s unique qualifications and desires. Once relevant jobs are available, the application delivers notifications based on the candidates’s preferences. Whether it’s instant notifications as opportunities arise or a curated digest delivered daily, weekly, or monthly to their email.

Now, let’s dissect the complexity of this problem statement into its constituent parts, each representing a sub-domain that plays a unique role in designing the entire solution. These sub-domains lay the foundation for our Choreography Pattern implementation, as discussed below:

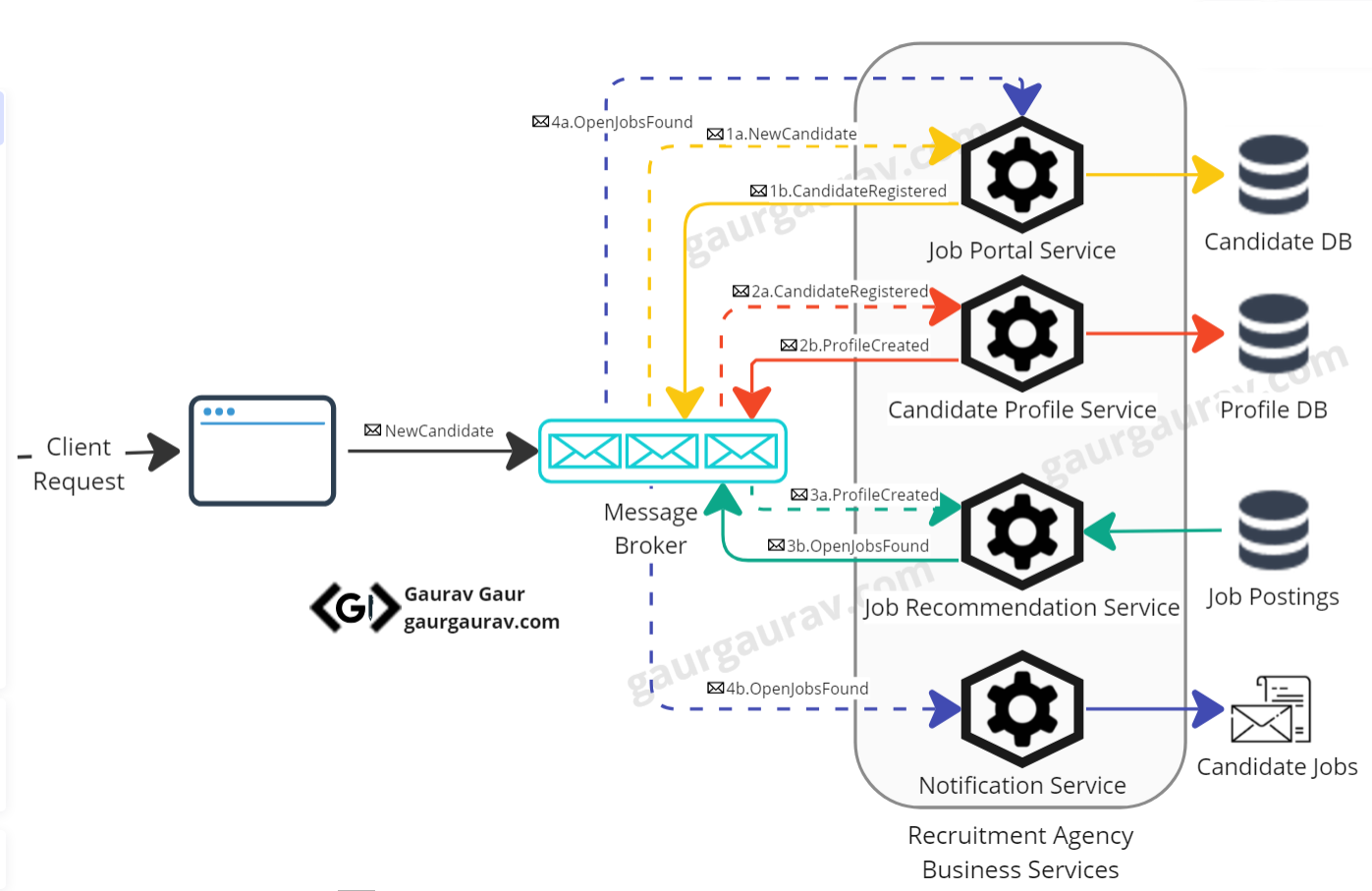

1. Job Portal Service

Candidates need to sign up as users for the recruitment agency on the web page of Job Portal Service. During registration, they are prompted to provide essential details, outline their preferences, and upload their resumes. The service validates the incoming data and stores the information in the candidate database. Upon successful registration, it then emits an event, such as CandidateRegistered, containing user details.

2. Candidate Profile Service

The Candidate Profile Service listens for the CandidateRegistered event. When it receives this event, the service fetches and parses the resume and combines it with the other information provided by the candidate to create a domain model. The domain model is not just a simple representation of the applicant’s data; instead, it categorizes the candidates based on their skill set, experience, and job preferences. The service persists this domain model in the candidate profile database, improving the job recommendation engine. It then triggers another event, such as ProfileCreated. This event signals the successful creation of the candidate’s profile.

3. Job Recommendation Service

The Job Recommendation Service continuously scans candidate profiles and job postings. When the ProfileCreated event arrives, it signals the Job Recommendation Service to refresh its cache. The service uses this updated information to create personalized job recommendations for candidates based on their skills and preferences. Once the query is complete and the service has its recommendations ready, it emits another event, such as OpenJobsFound consumed by both the Job Portal Service and the Notification Service. The Job Portal Service adds available open jobs to the candidate’s record so that candidates can see them when they log in.

4. Notification Service

The Notification Service subscribes to the OpenJobsFound event. The service can immediately notify the applicant about the available job openings. Alternatively, service can accumulate all the available job openings. The service will deliver the accumulated result to the candidate based on their preferences, daily, weekly, or monthly.

As we can observe, the entire execution flow operates through asynchronous communication among services, and there is no need for an orchestrator service to oversee the sequence of actions. This pattern offers several advantages. First and foremost, the absence of a central orchestrator service sets the stage for significant cost savings and a reduction in administrative overhead. Secondly, it improves system resilience. Since all events are routed through a message broker, even if one of the services temporarily goes offline, messages will not be lost. When the service is back online, it can seamlessly recover and process events from the message broker as if there were no interruptions.

Implementation Details

From the description above, it becomes evident that we require robust integration infrastructure, such as a message broker, empowering us to decouple the application. However, we must define a well-thought-out communication strategy among the services. We must decide on a few aspects to effectively implement the Choreography Pattern.

1. Command vs. Event

The first choice we should make is between a command and an event. A command invokes a specific action in a downstream application. When issued, the publisher expects a response, at least in the scenarios when it fails. It implies that the publisher has some knowledge of what behaviour the consumer should exhibit. It is worth noticing that command usually targets a single consumer and is much like a one-on-one conversation. It can introduce some level of coupling between the services.

Conversely, an event signifies something has occurred, leaving it to the downstream systems to decide a course of action in response. Events are not limited to a single consumer; they can have none, one, or even multiple consumers. Unlike conversation, the publisher typically doesn’t anticipate any response from downstream systems. Does this mean we should wholeheartedly embrace events? This decision is not straightforward either and needs further discussion.

2. Choosing the Right Event Pattern

If we prefer events, selecting message patterns can significantly impact performance. Martin Fowler has published an article on Event-Driven that comprehensively covers the four invaluable strategies.

- Event Notification

In the event notification pattern, the publisher emits events to inform downstream systems about changes within its domain. These events are concise notifications, providing minimal information such as an ID and a link for further exploration. The subscriber subscribes to the incoming event and requests additional details from the publisher for appropriate action. Event Notification can help reduce coupling and is easy to implement. However, it can become complex when the logical flow splits over multiple event notifications.

- Event Notifications with State

If we want to reduce the frequent chatter between the services, the publisher can send a payload having all the necessary details required for downstream action. Although the pattern reduces the number of calls between systems, it can introduce some complexities. <br>

Firstly, when there are multiple subscribers, the publisher faces the challenge of emitting a generic message that accommodates all subscribers. Secondly, this approach places an overhead on subscribers as they must now maintain the state of the data. But it also means that subscribers are self-sufficient and can respond to any incoming request even if the publisher is down.

- Event Sourcing

While persisting in the current state with every notification can solve most problems, there are scenarios when it becomes necessary to understand how we got there. Event sourcing is a pattern that can help in such circumstances as published events persist as records. It means the application preserves the entire event history and can reconstruct its state by replaying these records.

Imagine it like version control for the application states that we can use to trace and restore valid states in case of any failure. However, with all these benefits, it adds a layer of complexity to our application. We need to consider the edge cases, such as how to handle old events in scenarios of schema changes.

Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) is a pattern that elegantly separates reading operations from writing operations. While CQRS has broader applications, it can be combined with the above-discussed techniques to create an optimised solution. Although it may sound appealing to use CQRS, we should only adopt it with careful consideration, thoroughly researching and understanding the implications and benefits it brings. An in-depth exploration of CQRS is beyond the scope of this discussion.

3. Communication Styles & What-Ifs

Once we have decided on an architectural preference for event patterns, the next step is to choose a communication style. There are three options: Polling, where services inquire about updates at set intervals; Push, where updates are actively sent to subscribers; and, where services fetch updates as needed. Each has its own merits and serves a distinct purpose. <br>

We must also prepare for a series of ‘what-if’ scenarios. What if the message broker experiences a temporary failure? What if messages do not arrive in the anticipated order? What if a message gets lost in the network? These ‘ what-ifs’ can impact our architectural performance, and we must prepare for these unexpected interruptions.

Why Use the Choreography Pattern

The approach is especially beneficial when we need asynchronous communication and loose coupling. Below are a few scenarios when you should consider using the pattern:

- Consider the pattern when we need to replace or update services frequently. As services operate independently, they interact through asynchronous events. It means we can introduce components gracefully or retire old ones without disrupting the existing services.

- As the application and organization grow, the pattern supports this scaling and expansion. It empowers teams to strategically scale their efforts, separating concerns and operating autonomously on specific tasks.

- The pattern is a natural choice to implement serverless architecture. It means services are running when an event is triggered. The services consume the incoming event, process their task, and shut down when the operation is complete. It means that we are only charged for what we use, making it a cost-efficient production-ready solution.

- The pattern isn’t just about performance; it’s about versatility. It encourages the creation of decoupled, plug-and-play components, each addressing a specific business problem. These components can be reused across different scenarios and seamlessly integrated into the system wherever needed.

Important Considerations

In the previous section, we explored the implementations and advantages of using the pattern and how it can provide design flexibility. However, it comes at the cost of managing application flows. This section highlights a few complexities associated with the Choreography Pattern:

- Maintaining data consistency and integrity can be challenging in a choreographed system, especially for an incomplete business transaction when multiple services are required to update related data. The corrupted state might require a manual workaround and an appropriate alerting mechanism. Another approach is to use a service that listens to failed events and applies compensating transactions. The aim is to restore the previous valid state. However, we must tread with caution, considering what happens if the compensating transaction also fails.

- As business logic is distributed across multiple services, comprehending the overall system behaviour becomes increasingly challenging with a growing number. This increase underscores the need for up-to-date documentation and a comprehensive solution overview.

- We must design the services for error handling and failure recovery, as services bear the responsibility for the seamless execution of entire business transactions along with executing their operations. Consequently, each service must incorporate good practices such as retries and circuit breakers.

Summary

The Choreography Pattern is a powerful alternative to the Orchestration Pattern for addressing communication in a microservices architecture. Its decentralized, event-driven approach empowers microservices to collaborate autonomously, enhancing system scalability, agility, and resilience. By adopting the Choreography Pattern, organizations can unlock the maximum potential of microservices while navigating the challenges of distributed systems.

Discover more from WIREDGORILLA

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.