Beyond the severe toll of the coronavirus pandemic, perhaps no other disruption has transformed user experiences quite like how the tethers to our formerly web-biased era of content have frayed. We’re transitioning to a new world of remote work and digital content. We’re also experimenting with unprecedented content channels that, not too long ago, elicited chuckles at the watercooler, like voice interfaces, digital signage, augmented reality, and virtual reality.

Many factors are responsible. Perhaps it’s because we yearn for immersive spaces that temporarily resurrect the Before Times, or maybe it’s due to the boredom and tedium of our now-cemented stuck-at-home routines. But aural user experiences slinging voice content, and immersive user experiences unlocking new forms of interacting with formerly web-bound content, are no longer figments of science fiction. They’re fast becoming a reality in the here and now.

The idea of immersive experiences is all the rage these days, and content strategists and designers are now seriously examining this still-amorphous trend. Immersive experiences embrace concepts like geolocation, digital signage, and extended reality (XR). XR encompasses augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) as well as their fusion: mixed reality (MR). Sales of immersive equipment like gaming and VR headsets have skyrocketed during the pandemic, and content strategists are increasingly attuned to the kaleidoscope of devices and interfaces users now interact with on a daily basis to acquire information.

Immersive user experiences are becoming commonplace, and, more importantly, new tools and frameworks are emerging for designers and developers looking to get their hands dirty. But that doesn’t mean our content is ready for prime time in settings unbound from the web like physical spaces, digital signage, or extended reality. Recasting your fixed web content in more immersive ways will enable more than just newfangled user experiences; it’ll prepare you for flexibility in an unpredictable future as well.

Agnostic content for immersive experiences

These days, we interact with content through a slew of devices. It’s no longer the case that we navigate information on a single desktop computer screen. In my upcoming book Voice Content and Usability (A Book Apart, coming June 2021), I draw a distinction between what I call macrocontent—the unwieldy long-form copy plastered across browser viewports—and Anil Dash’s definition of microcontent: the kind of brisk, contextless bursts of content that we find nowadays on Apple Watches, Samsung TVs, and Amazon Alexas.

Today, content also has to be ready for contextless situations—not only in truncated form when we struggle to make out tiny text on our smartwatches or scroll through new television series on Roku but also in places it’s never ended up before. As the twenty-first century continues apace, our clients and our teams are beginning to come to terms with the fact that the way copy is consumed in just a few decades will bear no resemblance whatsoever to the prosaic browsers and even smartphones of today.

What do we mean by immersive content?

Immersive experiences are those that, according to Forrester, blur “the boundaries between the human, digital, physical, and virtual realms” to facilitate smarter, more interactive user experiences. But what do we mean by immersive content? I define immersive content as content that plays in the sandbox of physical and virtual space—copy and media that are situationally or locationally aware rather than rooted in a static, unmoving computer screen.

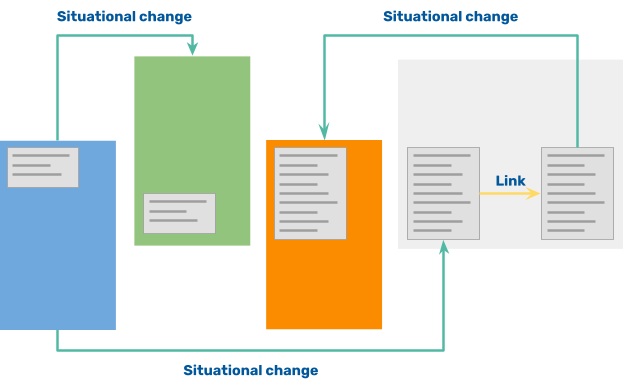

Whether a space is real or virtual, immersive content (or spatialcontent) will be a key way in which our customers and users deal with information in the coming years. Unlike voice content, which deals with time and sound, immersive content works with space and sight. Immersive content operates not along the axis of links and page changes but rather along situational changes, as the following figure illustrates.

Acknowledging the actual or imagined surroundings of where we are as human beings will have vast implications for content strategy, omnichannel marketing, usability testing, and accessibility. Before we dig deeper, let’s define a few clear categories of immersive content:

- Digital signage content. Though it may seem a misnomer, digital signage is one of the most widespread examples of immersive content already in use today. For example, you may have seen it used to display a guide of stores at a mall or to aid wayfinding in an airport. While still largely bound to flat screens, it’s an example of content in space.

- Locational content. Locational content involves copy that is delivered to a user on a personal device based on their current location in the world or within an identified physical space. Most often mediated through Bluetooth low-energy (BLE) beacon technology or GPS location services, it’s an example of content at a point in space.

- Augmented reality content. Unlike locational content, which doesn’t usually adjust itself seamlessly based on how users move in real-world space, AR content is now common in museums and other environments—typically as overlays that are superimposed over actual physical surroundings and adjust dynamically according to the user’s position and perspective. It’s content projected into real-world space.

- Virtual reality content. Like AR content, VR content is dependent on its imagined surroundings in terms of how it displays, but it’s part of a nonexistent space that is fully immersive, an example of content projected into virtual space.

- Navigable content. Long a gimmicky playground for designers and developers interested in pushing the envelope, navigable content is copy that users can move across and sift through as if it were a physical space itself: true content as space.

The following illustration depicts these types of immersive content in their typical habitats.

Why auditing immersive content is important

Alongside conversational and voice content, immersive content is a compelling example of breaking content out of the limiting box where it has long lived: the browser viewport, the computer screen, and the 8.5”x11” or broadsheet borders of print media. For centuries, our written copy has been affixed to the staid standards of whatever bookbinders, newspaper printing presses, and screen manufacturers decided. Today, however, for the first time, we’re surmounting those arbitrary barriers and situating content in contexts that challenge all the assumptions we’ve made since the era of Gutenberg—and, arguably, since clay tablets, papyrus manuscripts, and ancient scrolls.

Today, it’s never been more pressing to implement an omnichannel content strategy that centers the reality our customers increasingly live in: a world in which information can end up on any device, even if it has no tether to a clickable or scrollable setting. One of the most important elements of such a future-proof content strategy is an omnichannel content audit that evaluates your content from a variety of standpoints so you can manage and plan it effectively. These audits generally consist of several steps:

- Write a questionnaire. Each content item needs to be examined from the perspective of each channel through a series of channel-relevant questions, like whether content is legible or discoverable on every conduit through which it travels.

- Settle the criteria. No questionnaire is complete for a content audit without evaluation criteria that measure how the content performs and recommendation criteria that determine necessary steps to improve its efficacy.

- Discuss with stakeholders. At the end of any content audit, it’s important to leaf through the results and any recommendations in a frank discussion with stakeholders, including content strategists, editors, designers, and others.

In my previous article for A List Apart, I shared the work we did on a conversational content audit for Ask GeorgiaGov, the first (but now decommissioned) Alexa skill for residents of the state of Georgia. Such a content audit is just one facet of the multifaceted omnichannel content strategy along various dimensions you’ll need to consider. Nonetheless, there are a few things all content audits share in terms of foundational evaluation criteria across all content delivery channels:

- Content legibility. Is the content readable or easily consumable from a variety of vantage points and perspectives? In the case of immersive content, this can include examining verbosity tolerance (how long content can be before users zone out, a big factor in digital signage) and phantom references (like links and calls to action that make sense on the web but not on a VR headset).

- Content discoverability. It’s no longer guaranteed in immersive content experiences that every piece of content can be accessed from other content items, and content loses almost all of its context when displayed unmoored from other content in digital signs or AR overlays. For discoverability’s sake, avoid relegating content to unreachable siloes, whether content is inaccessible due to physical conditions (like walls or other obstacles) or technical ones (like a finicky VR headset).

Like voice content, immersive content requires ample attention to the ways in which users approach and interact with content in physical and virtual spaces. And as I write in Voice Content and Usability, it’s also the case that cross-channel interactions can influence how we work with copy and media. After all, how often do subway and rail commuters glance up while scrolling through service advisories on their smartphones to consult a potentially more up-to-date alert on a digital sign?

Digital signage content: Content in space

Signage has long been a fixture of how we find our way through physical spaces, ever since the earliest roads crisscrossed civilizations. Today, digital signs are becoming ubiquitous across shopping centers, university campuses, and especially transit systems, with the New York City subway recently introducing countdown clocks that display service advisories on a ticker along the bottom of the screen, just below train arrival times.

Digital signs can deliver critical content at important times, such as during emergencies, without the limitations imposed by the static nature of analog signs. News tickers on digital signs, for instance, can stretch for however long they need to, though succinctness is still highly prized. But digital signage’s rich potential to deliver immersive content also presents challenges when it comes to content modeling and governance.

Are news items delivered to digital signs simply teaser or summary versions of full articles? Without a fully functional and configurable digital sign in your office, how will you preview them in context before they go live? To solve this problem for the New York City subway, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) manages all digital signage content across all signs within a central Drupal content management system (CMS), which synthesizes data such as train arrival times from real-time feeds and transit messages administered in the CMS for arbitrary delivery to any platform across the network.

How to present content items in digital signs also poses problems. As the following figure illustrates, do you overtake the entire screen at the risk of obscuring other information, do you leave it in a ticker that may be ignored, or do you use both depending on the priority or urgency of the content you’re presenting?

While some digital signs have the benefit of touch screens and occupying entire digital kiosks, many are tasked with providing key information in as little space as possible, where users don’t have the luxury of manipulating the interface to customize the content they wish to view. The New York City subway makes a deliberate choice to allow urgent alerts to spill across the entire screen, which limits the sign’s usefulness for those who simply need to know when the next train is arriving in the interest of more important information that is relevant to all passengers—and those who need captions for loudspeaker announcements.

Auditing for digital signage content

Because digital signs value brevity and efficiency, digital signage content often isn’t the main focus of what’s displayed. Digital signs on the São Paulo metro, for instance, juggle service alerts, breaking news, and health advisories. For this reason, auditing digital signage content for legibility and discoverability is key to ensuring users can interact with it gracefully, regardless of how often it appears, how highly prioritized it is, or what it covers.

When it comes to legibility, ask yourself these questions and consider the digital sign content you’re authoring based on these concerns:

- Font size and typography. Many digital signs use sans-serif typefaces, which are easier to read from a distance, and many also employ uppercase for all text, especially in tickers. Consider which typefaces advance rather than obscure legibility, even when the digital sign content overtakes the entire screen.

- Angles and perspective. Is your digital sign content readily readable from various angles and various vantage points? Does the reflectivity of the screen impact your content’s legibility when standing just below the sign? How does your content look when it’s displayed to a user craning their neck and peering at it askew?

- Color contrast and lighting. Digital signs are no longer just fixtures of subterranean worlds; they’re above-ground and in well-lit spaces too. Color contrast and lighting strongly influence how legible your digital sign content can be.

As for discoverability, digital signs present challenges of both physical discoverability (can the sign itself be easily found and consulted?) and content discoverability (how long does a reader have to stare at the sign for the content they need to show up?):

- Physical discoverability. Are signs placed in prominent locations where users will come across them? The MTA was criticized for the poor placement of many of its digital countdown clocks in the New York City subway, something that can block a user from ever accessing content they need.

- Content discoverability. Because digital signs can only display so much content at once, even if there’s a large amount of copy to deliver eventually, users of digital signs may need to wait too long for their desired content to appear, or the content they seek may be too deprioritized for it to show up while they’re looking at the sign.

Both legibility and discoverability of digital sign content require thorough approaches when authoring, designing, and implementing content for digital signs.

Usability and accessibility in digital signage content

In addition to audits, in any physical environment, immersive content on digital signs requires a careful and bespoke approach to consider not only how content will be consumed on the sign itself but also all the ways in which users move around and refer to digital signage as they consult it for information. After all, our content is no longer couched in a web page or recited by a screen reader, both objects we can control ourselves; instead, it’s flashed and displayed on flat screens and kiosks in physical spaces.

Consider how the digital sign and the content it presents appear to people who use mobility aids such as wheelchairs or walkers. Is the surrounding physical environment accessible enough so that wheelchair users can easily read and discover the content they seek on a digital sign, which may be positioned too high for a seated reader? By the same token, can colorblind and dyslexic people read the chosen typeface in the color scheme it’s rendered in? Is there an aural equivalent of the content for Blind people navigating your digital signage, in close proximity to the sign itself, serving as synchronized captions?

Locational content: Content at a point in space

Unlike digital signage content, which is copy or media displayed in a space, locational (or geolocational) content is copy or media delivered to a device—usually a phone or watch—based on a point in space (if precise location is acquired through GPS location services) or a swath of space (typically driven by Bluetooth Low Energy beacons that have certain ranges). For smartphone and smartwatch users, GPS location services can often pinpoint a relatively accurate sense of where a person is, while Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) beacons can triangulate their position based on devices that have Bluetooth enabled.

Though BLE beacons remain a fairly finicky and untested realm of spatial technology, they’ve quickly gained traction in large shopping centers and public spaces such as airports where users agree to receive content relevant to their current location, most often in the form of push notifications that whisk users away into a separate view with more comprehensive information. But because these tiny chunks of copy are often tightly contained and contextless, teams designing for locational content need to focus on how users interact with their devices as they move through physical spaces.

Auditing for locational content

Fortunately, because locational content is often delivered to the same visual devices that we use on a regular basis—smartphones, smartwatches, and tablets—auditing for content legibility can embrace many of the same principles we employ to evaluate other content. For discoverability, some of the most important considerations include:

- Locational discoverability. BLE beacons are notorious for their imprecision, though they continue to improve in quality. GPS location, too, can be an inaccurate measure of where someone is at any given time. The last thing you want your customers to experience is an incorrect triangulation of where they are leading to embarrassing mistakes and bewilderment when unexpected content travels down the wire.

- Proximity. Because of the relative lack of precision when it comes to BLE beacons and GPS location services, placing content items too close together in a coordinate map may trigger too many notifications or resource deliveries to a user, thus overwhelming them, or a certain content item may inadvertently supersede another because they’re spaced too closely together.

As push notifications and location sharing become more common, locational content is rapidly becoming an important way to funnel users toward somewhat longer-form content that might otherwise go unnoticed when a customer is in a brick-and-mortar store.

Usability and accessibility in locational content

Because locational content requires users to move around physical spaces and trigger triangulation, consider how different types of users will move and also whether unforeseen issues can arise. For example, researchers in Japan found that users who walk while staring at their phones are highly disruptive to the flow and movement of those around them. Is your locational content possibly creating a situation where users bump into others, or worse, get into accidents? For instance, writing copy that’s quick and to the point or preventing notifications from being prematurely dismissed could allow users to ignore their devices until they have time to safely glance at them.

Limited mobility and cognitive disabilities can place many disabled users of locational content at a deep disadvantage. While gamification may encourage users to seek as many items of locational content as possible in a given span of time for promotional purposes, consider whether it excludes wheelchair users or people who encounter obstacles when switching between contexts rapidly. There are good use cases for locational content, but what’s compelling for some users might be confounding for others.

AR and VR content: Content projected into space

Augmented reality, once the stuff of science fiction holograms and futuristic cityscapes, is becoming more available to the masses thanks to wearable AR devices, high-performing smartphones and tablets, and innovation in machine vision capabilities, though the utopian future of true “holographic” content remains as yet unrealized. Meanwhile, virtual reality has seen incredible growth over the pandemic as homebound users—by interacting with copy and media in fictional worlds—increasingly seek escapist ways to access content normally spread across flat screens.

While AR and VR content is still in its infancy, the vast majority is currently couched in overlays that are superimposed over real-world environments or objects and can be opaque (occupying some of a device’s field of vision) or semi-transparent (creating an eerie, shimmery film on which text or media is displayed). Thanks to advancements in machine vision, these content overlays can track the motion of perceived objects in the physical or virtual world, bamboozling us into thinking these overlays are traveling in our fields of vision just like the things we see around us do.

Formerly restricted to realms like museums, expensive video games, and gimmicky prototypes, AR and VR content is now becoming much more popular among companies that are interested in more immersive experiences capable of delivering content alongside objects in real-life brick-and-mortar environments, as well as virtual or imagined landscapes, like fully immersive brand experiences that transport customers to a pop-up store in their living room.

To demonstrate this, my former team at Acquia Labs built an experimental proof of concept that examines how VR content can be administered within a CMS and a pilot project for grocery stores that explores what can happen when product information is displayed as AR content next to consumer goods in supermarket aisles. The following illustration shows, in the context of this latter experiment, how a smartphone camera interacts with a machine vision service and a Drupal CMS to acquire information to render alongside the item.

Auditing for AR and VR content

Because AR and VR content, unlike other forms of immersive content, fundamentally plays in the same sandbox as the real world (or an imaginary one), legibility and discoverability can become challenging. The potential risks for AR and VR content are in many regards a fusion of the problems found in both digital signage and locational content, encompassing both physical placement and visual perspective, especially when it comes to legibility:

- Content visibility. Is the AR or VR overlay too transparent to comfortably read the copy or view the image contained therein, or is it so opaque that it obscures its surroundings? AR and VR content must coexist gracefully with its exterior, and the two must enhance rather than obfuscate each other. Does the way your content is delivered compromise a user’s feeling of immersion in the environment behind it?

- Content perspective. Unless you’re limited to a smartphone or similar handheld device, many AR and VR overlays, especially in immersive headsets, don’t display content or media as an immobile rectangular box, as it defeats the purpose of the illusion and can be jarring to users as they adjust their field of vision, breaking them out of the fantasy you’re hoping to create. For this reason, your AR or VR experience must not only dictate how environments and objects are angled and lit but also how the content associated with them is perceived. Is your content readable from various angles and points in the AR view or VR world?

When it comes to discoverability of your AR and VR content, issues like accuracy in machine vision and triangulation of your user’s location and orientation become much more important:

- Machine vision. Most relevantly for AR content, if your copy or media is predicated on machine vision that perceives an object by identifying it according to certain characteristics, how accurate is that prediction? Does some content go undiscovered because certain objects go undetected in your AR-enabled device?

- Location accuracy. If your content relies on the user’s current location and orientation in relation to some point in space, as is common in both AR and VR content use cases, how accurately do devices dictate correct delivery at just the right time and place? Are the ranges within which content is accessible too limited, leading to flashes of content as you take a step to the left or right? Are there locations that simply can’t be reached, leading to forever-siloed copy or media?

Due to the intersection of technical considerations and design concerns, AR and VR content, like voice content and indeed other forms of immersive content, requires a concerted effort across multiple teams to ensure resources are delivered not just legibly but also discoverably.

Usability and accessibility in AR and VR content

Out of all the forms of immersive content we’ve covered so far, AR and VR content is possibly the medium that demands the most assiduously crafted solutions in accessibility testing and usability testing. Because AR and VR content, especially in headsets or wearable devices, requires motion through real or imagined space, its impact on accessibility cannot be overstated. Adding a third dimension—and arguably, a fourth: time—to our perception of content requires attention not only to how content is accessed but also all the other elements that comprise a fully immersive visual experience.

VR headsets commonly induce virtual reality motion sickness in many individuals. Poorly implemented transitions between states occurring in quick succession where content is visible and then invisible, and then visible again, can lead to epileptic seizures if not built with the utmost care. Finally, users moving quickly through spaces may inadvertently trigger vertigo in themselves or even collide with hazardous objects, resulting in potentially serious injuries. There’s a reason we aren’t wearing wearable headsets outside carefully secured environments.

Navigable content: Content as space

This is only the beginning of immersive content. Increasingly, we’re also toying with ideas that seemed harebrained even a few decades ago, like navigable content—copy and media that can be traversed as if the content itself were a navigable space. Imagine zooming in and out of tracts of text and stepping across glyphs like hopping between islands in a Super Mario game. Ambitious designers and developers are exploring this emerging concept of navigable content in exciting ways, both in and out of AR and VR. In many ways, truly navigable content is the endgame of how virtual reality presents information.

Imagining an encyclopedia that we can browse like the classic 1990s opening sequence of the BBC’s Eyewitness television episodes is no longer as far-fetched as we think. Consider, for instance, Robby Leonardi’s interactive résumé, which invites you to play a character as you learn about his career, or Bruno Simon’s ambitious portfolio, where you drive an animated truck around his website. For navigable content, the risks and rewards for user experience and accessibility remain largely unexplored, just like the hazy fringes of the infinite maps VR worlds make possible.

Conclusion

The story of immersive content is in its early stages. As newly emerging channels for content see greater adoption, requiring us to relay resources like text and media to never-before-seen destinations like digital signage, location-enabled devices, and AR and VR overlays, the demands on our content strategy and design approaches will become both fascinating and frustrating. As seemingly fantastical new interfaces continue to emerge over the horizon, we’ll need an omnichannel content strategy to guide our own journeys as creatives and to orient the voyages of our users into the immersive.

Content audits and effective content strategies aren’t just the domain of staid websites and boxy mobile or tablet interfaces—or even aurally rooted voice interfaces. They’re a key component of our increasingly digitized spaces, too, cornerstones of immersive experiences that beckon us to consume content where we are at any moment, unmoored from a workstation or a handheld. Because it lacks long-standing motifs of the web like context and clickable links, immersive content invites us to revisit our content with a fresh perspective. How will immersive content reinvent how we deliver information like the web did only a few decades ago, like voice has done in the past ten years?

Only the test of time, and the allure of immersion, will tell.

Discover more from WIREDGORILLA

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.