This is a direct repost of the original article on my blog.

In my team we run “masterclasses” every couple of weeks, where someone in the team presents a topic to the rest of the team.

This article is basically the content of the class on regular expressions (otherwise known as regex) I gave recently.

It’s an introduction to the basics of regular expressions. There are many like it, but this is mine.

What is a regular expression (or regex)?

Wikipedia defines regular expressions as:

“a sequence of characters that define a search pattern”

They are available in basically every programming language, and you’ll probably most commonly encounter them used for string matches in conditionals that are too complicated for simple logical comparisons (like “or”, “and”, “in”).

A couple of examples of regular expressions to get started:

[ -~] |

Any ASCII character (ASCII characters fall between space and “~”) |

^[a-z0-9_-]{3,15}$ |

Usernames between 3 and 15 characters |

When to use regex

Use regular expressions with caution. The complexity of regex carries a cost.

Avoid coding in regex if you can

‘Some people, when confronted with a problem, think “I know, I’ll use regular expressions.” Now they have two problems.’ – Jamie Zawinski

In programming, only use regular expressions as a last resort. Don’t solve important problems with regex.

- regex is expensive – regex is often the most CPU-intensive part of a program. And a non-matching regex can be even more expensive to check than a matching one.

- regex is greedy – It’s extremely easy to match much more than intended, leading to bugs. We have multiple times had problems with regexes being too greedy, causing issues in our sites.

- regex is opaque – Even people who know regex well will take a while to pick apart a new regex string, and are still likely to make mistakes. This has a huge cost to project maintenance in the long run. (Check out this amazing regex for RFC822 email addresses)

Always try to be aware of all the language features at your disposal for operating on and checking strings, that could help you avoid regular expressions. In Python, for example, the in keyword, the powerful [] indexing, and string methods like contains and startswith (which can be fed either strings of tuples for multiple values) can be combined very effectively.

Most importantly, regexes should not be used for parsing strings. You should instead use or write a bespoke parser. For example, you can’t parse HTML with regex (in Python, use BeautifulSoup; in JavaScript, use the DOM).

When to code in regex

Of course, there are times when regular expressions can or should be used in programs:

- When it already exist and you have to maintain it (although if you can remove it, you should)

- String validation, where there’s no other option

- String manipulation (substitution), where there’s no other option

If you are writing anything more than the most basic regex, any maintainers are unlikely to be able to understand your regex easily, so you might want to consider adding liberal comments. E.g. this in Python:

>>> pattern = """

^ # beginning of string

M{0,4} # thousands - 0 to 4 M's

(CM|CD|D?C{0,3}) # hundreds - 900 (CM), 400 (CD), 0-300 (0 to 3 C's), # or 500-800 (D, followed by 0 to 3 C's)

(XC|XL|L?X{0,3}) # tens - 90 (XC), 40 (XL), 0-30 (0 to 3 X's), # or 50-80 (L, followed by 0 to 3 X's)

(IX|IV|V?I{0,3}) # ones - 9 (IX), 4 (IV), 0-3 (0 to 3 I's), # or 5-8 (V, followed by 0 to 3 I's)

$ # end of string """

>>> re.search(pattern, 'M', re.VERBOSE) Other great uses for regex

Regular expressions can be extremely powerful for quickly solving problems for yourself, where future maintenance is not a concern. E.g.:

- Grep (or Ripgrep), Sed, Less and other command line tools

- In editors (e.g. VSCode), for quickly reformatting text

It’s also worth taking advantage of opportunities to use regex in these ways to practice your regex skills.

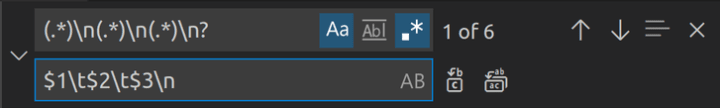

For example, I recently used the following regex substitution in VSCode to format a dump of text into a table format:

How to use regex

Bear in mind that regular expressions parsers come in a few varieties. Basically, every language implements its own parser. However, Perl’s regex parser is the gold standard. If you have a choice, use Perl Compatible Regular Expressions.

What regex looks like

The traditional way to write a regular expression is by surrounding it with slashes.

/^he[l]{2}owworld$/This is how they’re written in Perl and JavaScript, and in many command-line tools like Less.

Many more modern languages (e.g. Python), however, have opted not to include a native regex type, and so regular expressions are simply written as strings:

r"^he[l]{2}owworld$"Common regex characters

. |

Matches any single character (except newlines, normally) |

|

Escape a special character (e.g. . matches a literal dot) |

? |

The preceding character may or may not be present (e.g. /hell?o/ would match hello or helo) |

* |

Any number of the preceding character is allowed (e.g. .* will match any single-line string, including an empty string, and gets used a lot) |

+ |

One or more of the preceding character (.+ is the same as .* except that it won’t match an empty string) |

| |

“or”, match the preceding section or the following section (e.g. hello|mad will match “hello” or “mad”) |

() |

group a section together. This can be useful for conditionals ((a|b)), multipliers ((hello)+), or to create groups for substitutions (see below) |

{} |

Specify how many of the preceding character (e.g. a{12} matches 12 “a”s in a row) |

[] |

Match any character in this set. - defines ranges (e.g. [a-z] is any lowercase letter), ^ means “not” (e.g. [^,]+ match any number of non-commas in a row) |

^ |

Beginning of line |

$ |

End of line |

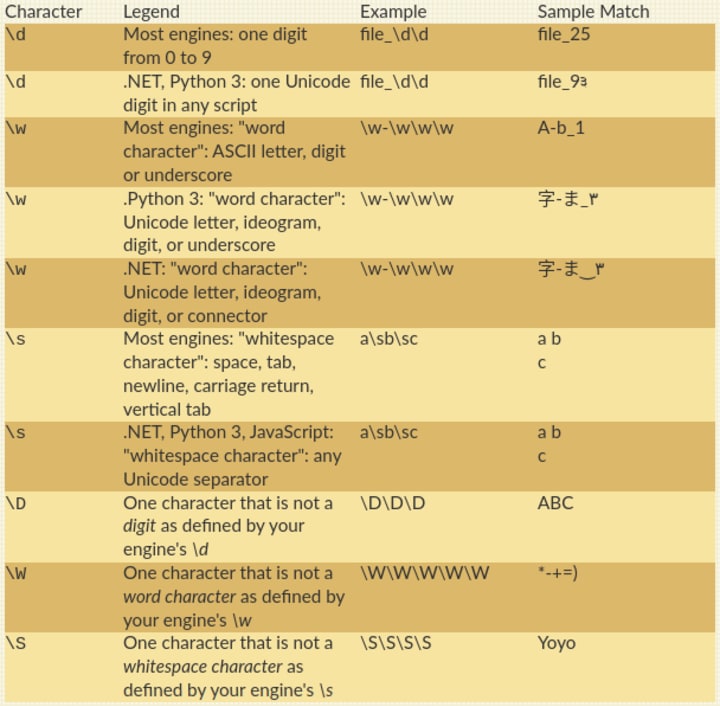

Character shortcuts in regex

In most regex implementations, you can use backslash followed by a letter (x) as a shortcut for a character set. Here’s a list of some common ones from rexegg.com’s regex cheat sheet.

Regex in conditionals

The simplest use-case for regexes in programming is a string comparison. This looks different in different languages, e.g.:

// Perl

if ( "hello world" =~ /^he[l]{2}osworld$/ ) {..}// JavaScript

if( /^he[l]{2}osworld$/.test("hello world") ) {..}# Python

import re

if re.match(r"^he[l]{2}osworld$", "hello world"): ..Regex in substitutions

You can also use regex to manipulate strings through substitution. In the following examples, “mad world” will be printed out:

// Perl

$hw = "hello world"; $hw =~ s/^(he[l]{2}o)s(world)$/mad 2/; print($hw)// JavaScript

console.log("hello world".replace(/^(he[l]{2}o)s(world)$/, "mad $2"))# Python

import re

print(re.replace(r"^(he[l]{2}o)s(world)$", r"mad 2", "hello world"))Regex modifiers

You can alter how regular expressions behave based on a few modifiers. I’m just going to illustrate one here, which is the modifier to make regex case insensitive. In Perl, JavaScript and other more traditional regex contexts, the modifiers are added after the last /. More modern languages often user constants instead:

// Perl

if ( "HeLlO wOrLd" =~ /^he[l]{2}osworld$/i ) {..}// JavaScript

if( /^he[l]{2}osworld$/i.test("HeLlO wOrLd") ) {..}# Python

import re

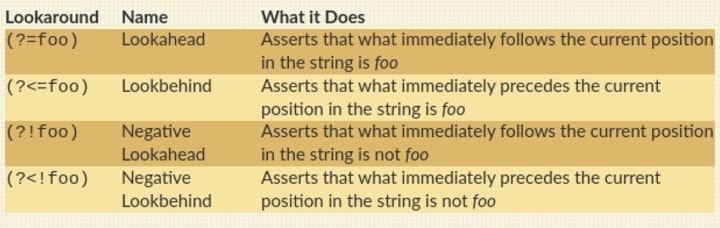

if re.match(r"^he[l]{2}osworld$", "HeLlO wOrLd", flags=re.IGNORECASE): ..Lookahead and lookbehind in regex

These are only supported in some implementations of regular expressions, and give you the opportunity to match strings that precede or follow other strings, but without including the prefix or suffix in the match itself:

(Again, taken from rexegg.com’s regex cheat sheet)

Regex resources

That is all I have for now. If you want to learn more, there’s are a lot of useful resources out there:

- Rexegg.com – Many great articles on most aspects of regex

- Regex101 – A tester for your regex, offering a few different implementations

- iHateRegex – A collection of example regex patterns for matching some common types of strings (e.g. phone number, email address)

- The official Perl Compatible Regular Expressions documentation

![6 new features you’ve got to know! single element animation & more! | what’s hot in canva ð¥ [ep. 04]](https://wiredgorilla.com/wp-content/plugins/wp-fastest-cache-premium/pro/images/blank.gif)