When most of us look out at the ocean, we see a mostly flat blue surface stretching to the horizon. It’s easy to imagine the sea beneath as calm and largely static – a massive, still abyss far removed from everyday experience.

But the ocean is layered, dynamic and constantly moving, from the surface down to the deepest seafloor. While waves, tides and currents near the coast are familiar and accessible, far less is known about what happens several kilometres below, where the ocean meets the seafloor.

Our new research, published in the journal Ocean Science, shows water near the the seafloor is in constant motion, even in the abyssal plains of the Pacific Ocean. This has important consequences for climate, ecosystems and how we understand the ocean as an interconnected system.

Enter the abyss

The central and eastern Pacific Ocean include some of Earth’s largest abyssal regions (places where the sea is more than 3,000 metres deep). Here, most of the seafloor lies four to six kilometres below the surface. It is shaped by vast abyssal plains, fracture zones and seamounts.

It is cold and dark, and the water and ecosystems here are under immense pressure from the ocean above.

Just above the seafloor, no matter the depth, sits a region known as the bottom mixed layer. This part of the ocean is relatively uniform in temperature, salinity and density because it is stirred through contact with the seafloor.

Rather than a thin boundary, this layer can extend from tens to hundreds of metres above the seabed. It plays a crucial role in the movement of heat, nutrients and sediments between the pelagic ocean and the seabed, including the beginning of the slow return of water from the bottom of the ocean toward the surface as part of global ocean circulation.

Observations focused on the bottom mixed layer are rare, but this is beginning to change. Most ocean measurements focus on the upper few kilometres, and deep observations are scarce, expensive and often decades apart.

In the Pacific especially, scientists have long known that cold Antarctic waters flow northward, along topographic features such as the Tonga-Kermadec Ridge and the Izu-Ogasawara and Japan Trenches.

But the finer details of how these waters interact with seafloor features in ways that intermittently stir and reshape the bottom layer of the ocean has remained largely unknown.

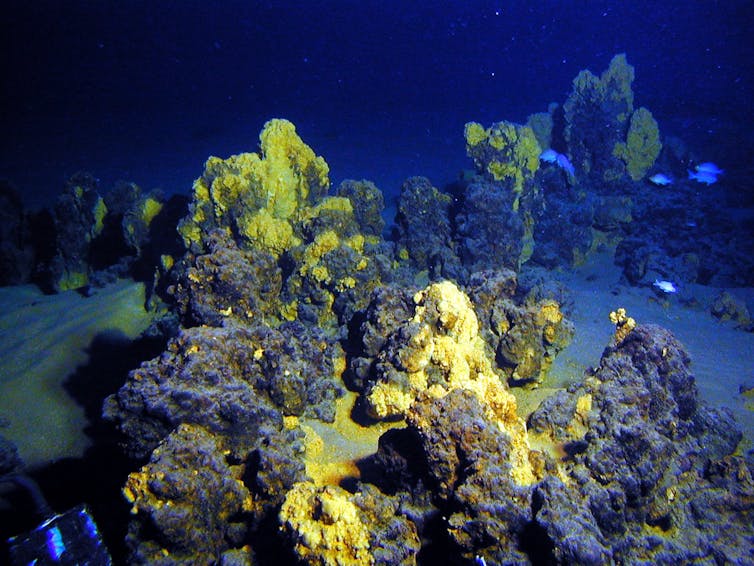

NOAA Photo Library

Investigating the abyss

To investigate the Pacific abyssal ocean, my colleagues and I combined new surface-to-seafloor measurements collected during a trans-Pacific expedition with high-quality repeat data about the physical features of the ocean gathered over the past two decades.

These observations allowed us to examine temperature and pressure all the way down to the seafloor over a wide range of latitudes and longitudes.

We then compared multiple scientific methods for identifying the bottom mixed layer and used machine learning techniques to understand what factors best explain the variations in its thickness.

Rather than being a uniform layer, we found the bottom mixed layer in the abyssal Pacific varies dramatically. In some regions it was less than 100m thick; in others it exceeded 700m.

This variability is not random; it’s controlled by the seafloor depth and the interactions between waves generated by surface tides and rough landscapes on the seabed.

In other words, the deepest ocean is not quietly stagnant as is often imagined. It is continually stirred by remote forces, shaped by seafloor features, and dynamically connected to the rest of the ocean above.

Just as coastal waters are shaped by waves, currents and sediment movement, the abyssal ocean is shaped by its own set of drivers. However, it is operating over larger distances and longer timescales.

NOAA Photo Library

Connected to the rest of the world

This matters for several reasons.

First, the bottom mixed layer influences how heat is stored and redistributed in the ocean, affecting long-term climate change. Some ocean and climate models still simplify seabed mixing, which can lead to errors in how future climate is projected.

Second, it plays a role in transporting sediment and seabed ecosystems. As interest grows in deep-sea mining and other activities on the high seas, understanding how the seafloor environment changes, and importantly how seafloor disturbances might spread, becomes increasingly important.

Our results highlight how little of the deep ocean we actually observe.

Large areas of the abyssal Pacific remain effectively unsampled, even as international agreements such as the new UN High Seas Treaty seek to manage and protect these regions.

The deep ocean is not a silent, static place. It is active, connected to the oceans above and changing. If we want to make informed decisions about the future of the high seas, we need to understand what’s happening at the very bottom in space and time.